An Introduction to Triads for the Bass Guitar

Using Chord Tones as a Starting Point — And Shape-Shifting, Too

One time back in the 1970s, I was in Grubstake Village (a very small community along Highway 49 in Calaveras County that doesn’t even exist anymore). I was there to listen to a rock band rehearse. At first, as I walked up, all I heard was the thump-thump-thumping of the bass guitar. When I got closer, though, I began to hear the drums, and finally the guitar (you may have also noticed this when hearing bands from a distance: the low tones of the bass carry further than the other instruments). Once I was in the room with the three young musicians, though, I was surprised to hear that all three instruments seemed to be about the same volume.

The guitarist and drummer were pretty good, but the bassist was bitter about his role in the band. This was not because he got the short end of the stick by being relegated to playing the bass, but because he was mediocre at it (to be generous). He kept complaining that playing bass was boring, for (as he understood it) all one does when playing that instrument is to play the root of the chord being played by the guitarist on beats 1 and 3, and the 5th on beats 2 and 4. For example, in the key of A, he would play a A on beats 1 and 3, and an E on beats 2 and 4, over and over again —shifting his hand up and down the fretboard on the songs’ chord changes, but sticking with the same tired old groove. No wonder he was bored out of his skull and constantly whining.

And so, yes, his playing was very boring — he kept plunking out the same pattern on every song. The only thing that changed, as far as his bass playing was concerned, was the tempo (dictated by the drummer) and the key of the song (dictated by the guitarist, the leader of the band).

Of course, it’s not true that all a bassist can play — even in a garage rock band (although this was, to be precise, a cabin rock band, as they practiced in an empty and uninhabited cabin there in Grubstake Village) — is the root and 5th of the chord, nor is it true that you must play straight quarter notes (root, 5th, root, 5th, ad infinitum ad nauseum). In other words, you can and should use a variety of note lengths (sixteenth, eight, quarter, half, whole) along with syncopation (play some notes on the upbeat).

You can add such variety even while sticking with a very small number of notes per chord, though. Many bass riffs actually only use the chord tones, or a triad: three notes, namely the root, the 3rd, and the 5th of the chord.

For those unfamiliar with the terms used above, just know that the root is the note with the same name as the chord (the root of a G chord is a G note, the root of a B chord is a B note, etc.) Also, perceive that the ordinal numbers follow the “do-re-mi” major scale made famous in The Sound of Music. In other words:

do = root (1st note in the major scale)

re = 2nd note in the major scale

mi = 3rd note “”

fa = 4th note “”

so = 5th note “”

la = 6th note “”

ti = 7th note “”

do = 8th note of the chord, or the octave of the first, or root, note (“that brings us back to ‘do’,” as they sang in that old film). In other words, the second ‘do’ is the same note as the first ‘do,’ but an octave higher.

As an example, in the key of A major, the notes in the scale are A, B, C#/Db, D, E, F#/Gb, G#/Ab, and then back to A (an octave higher than the first A).

Scales contain the majority of possible notes (7 out of 12 in the example above, not counting the second ‘do’).

A compromise between just playing two notes (the root and the 5th) and playing all the notes of the scale that often works well and is at least a good starting point is to play the aforementioned chord tones/triads — that is to say, the root, 3rd, and 5th, also known (in the key of A) as A, C#/Db, and E.

Sticking with just three notes in one spot on the fretboard, though, could easily lead to boredom, both for the player and the listeners. After all, playing three notes only provides 50% more note variety than sticking with only two notes, the root and the 5th. Something that helps invigorate the player and the listener is when the bassist plays those notes all around the fretboard wherever they appear. Not only is the tone different, even when playing the same notes, when played on different strings, but different patterns of where those notes appear in relation to each other on the fretboard can also inspire you to break out of a rut of always tending to play certain riffs or grooves (which can happen when using the same finger positioning on the same part of the fretboard all of the time).

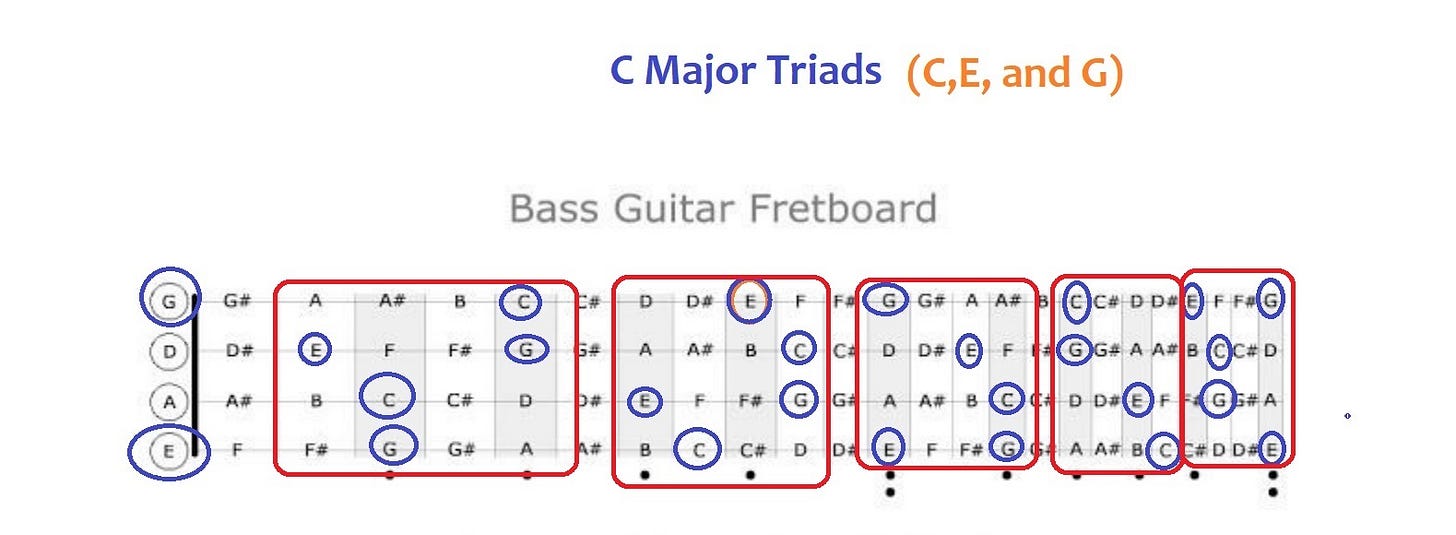

As an example, what you see in the image below is a diagram of a bass guitar’s fretboard with all the notes labeled. This shows all the places where you can play the chord tones or triad of a C chord (there are 12 different major keys: A, A#/Bb, B, C, C#/Db, D, D#/Eb, E, F, F#/Gb, G, and G#/Ab, but I’m just showing you the one (C) for brevity’s sake).

What is indicated by the slashes between sharp (#) and flat (b) notes is that those two keys, chords, or notes that lie between "natural" notes can be designated as either a sharp version of the lower note, or a flatted version of the higher note. For example, C# and Db are different names for the same note, the one in between a C and a D.This chart is based on one provided at www.garydeaconguitar.blogspot.com

And here’s a value-added example of the same chart with the basic triad shape (root under the middle finger, third under the index finger, and fifth under the pinky) rectangled:

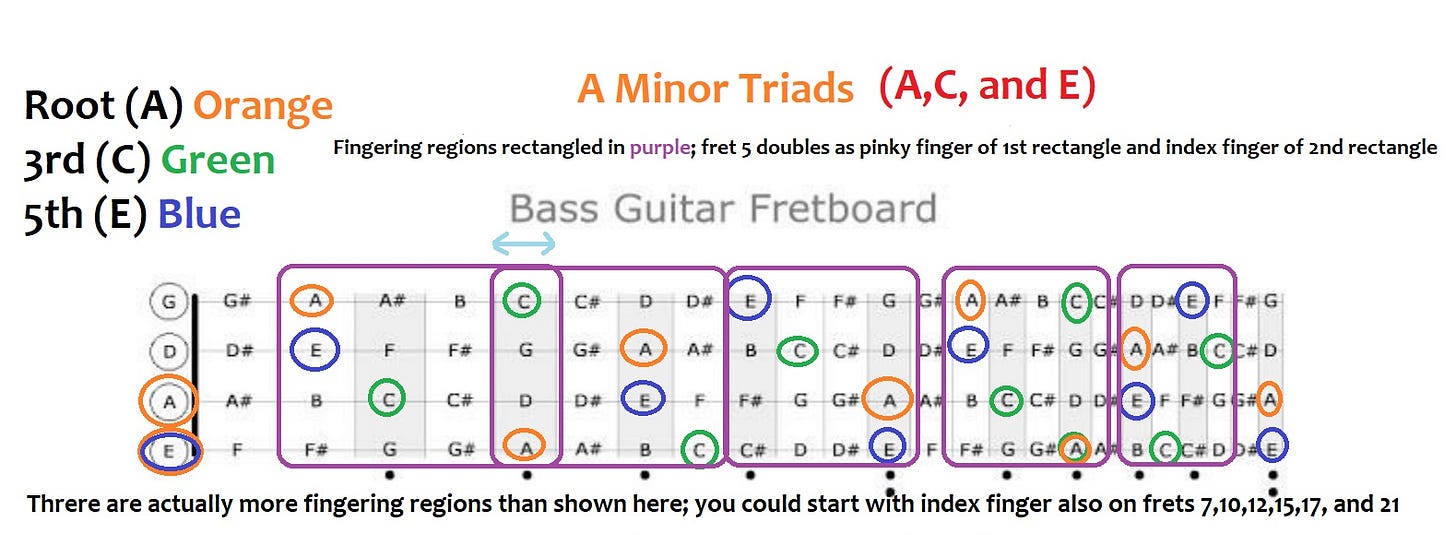

Here is yet another chart, showing different spots on the fretboard you can move to and cover with your fretting hand (index finger on the first fret of the section rectangled, middle finger on the second, ring finger on the third, and pinky on the fourth):

I will later add an example of the same sort but for the triad/chord tones of a minor chord. The only difference between a major triad and a minor triad is the 3rd — the root (perhaps obviously) and the 5th remaining the same.

You can adapt this chart to other keys easily enough — shift it one fret down (toward the nut/head) for a B chord, or 2 frets up (toward the bridge/pickups) for a D chord, etc.

NOTE: Much more about playing the bass, and chord scales, and triads, etc. etc. as well as every other bass-related topic for all genres of music and levels of skill, can be found at Scotts Bass Lessons. I am a “card-carrying” member of that bass academy (I literally paid my dues to them to be such), but am not affiliated with them in the sense of benefiting from your involvement with them (if that occurs).UPDATED THE NEXT DAY (8/6/2023)

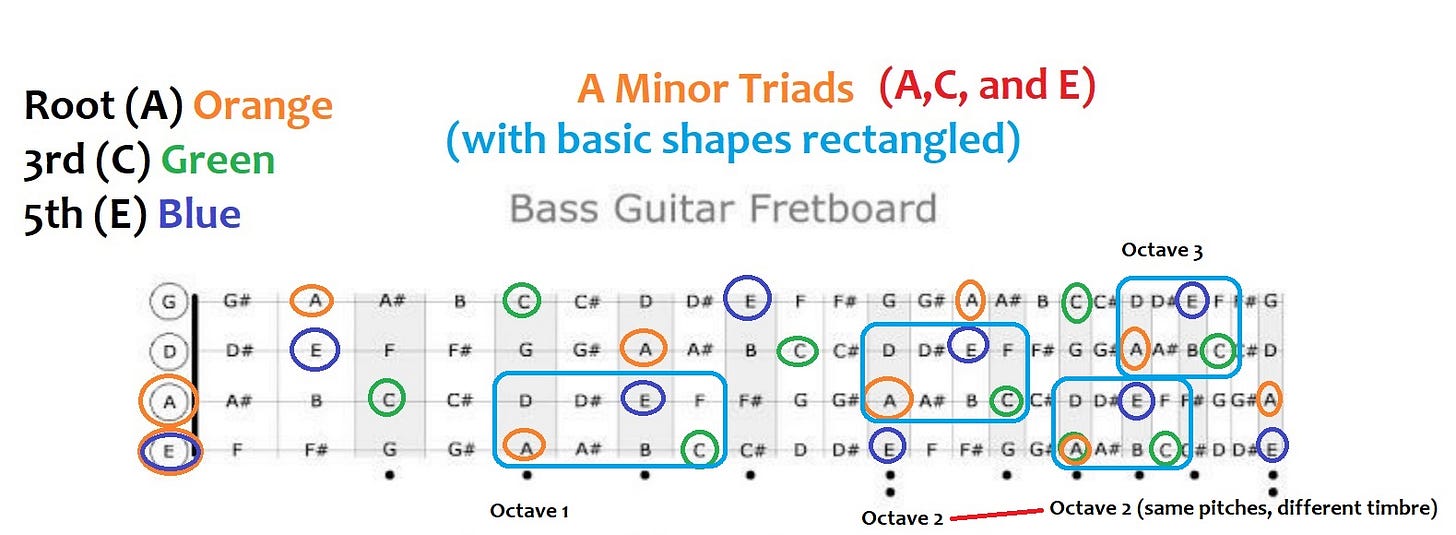

As I promised (not solemnly, but still more-or-less guaranteed), here are a couple of charts for the A minor triad:

And here are the fingering position rectangles (I could have rectangled my head off here, but the result would have been utterly confusing due to the scads of overlapping). See the note at the bottom of the image.

Note that, as mentioned earlier, many song’s bass riffs are based (pun not intended, but gladly retained when noticed) wholly on just those three notes, the chord tones or triad of a major or minor chord. One example, or near-example, anyway, is the song Fever covered by Peggy Lee in 1958 , with either Max Bennett or Joe Moondragon manning the four-string (depending on which source is more dependable). Lee’s version of Fever is made up mainly of the three notes of the A minor triad (A, C, and E) with the sole exception being use of the 7th (ti) note (G#/Ab) near the end of the riff.

NOTE: Yeah, yeah, it’s actually Joe Mondragon, not Moondragon, but if my name was Mondragon I would definitely go by Moondragon instead. In fact, I would gladly change my first name from Benedict to Moondragon if it weren’t so expensive and such a hassle to do it.