One of the mantras I often heard growing up was “Sports builds character.”

I didn’t really know what it meant, but I gladly accepted it as true, since it obviously meant that sports was considered a good thing, and I loved sports. It gave me permission, so to speak, to “waste time” simply having fun.

Later, when I realized what was meant by the statement, I wanted to think it was true, but couldn’t see how that was really the case. After all, how could throwing, catching, hitting, aiming, and chasing balls make one a better person? Playing sports was indeed fun, often even exhilarating, but how could engaging in something which just seemed like an exciting pastime mold my teammates and myself into more estimable and worthy people? I still didn’t grasp the logic behind the statement, as welcome as it was for me to hear it stated as an accepted truth.

Now I understand better what is meant by that phrase. But is it true? Does participation in sports build character?

To tackle this conundrum, we first need to agree on the definition of what is meant, exactly, by the word “character.”

Before we even come to an agreement on an accepted definition for that word, though, perhaps it should be noted that we are not here speaking of “characters,” such as those referred to when people say things like, “Ol’ Harry was really a character! He once climbed up the water tower and took a swim in the town’s elevated reservoir! Too bad he was too drunk to climb back out again” or “Aunt Sally was really quite the character – she once put hemlock in her husband’s tea, just to see what would happen!” or “Ned the Nerd is a real character; before eating them, he organizes his Skittles alphabetically by flavor: first he eats the grape ones, then the green apple, thereafter the lemon, then orange, then pomegranate-pear-peach-papaya-passionfruit-pickle, and finally the strawberry ones.”

Those sorts of “characters” can be described as “entertainingly quirky individuals” or simply as “weird dudes” (or dudettes).

SPORTS (OR ANY TYPE OF FAME) SPOTLIGHTS “CHARACTERS”

As far as the just-mentioned type of “characters” go, they can be found in all walks of life, not just sports. One doesn’t have to be famous, or an athlete, to be “a character.” They just become widely-known for their idiosyncrasies when they are already famous as a result of being prominent athletes (or actors, musicians, politicians, criminals, or what have you).

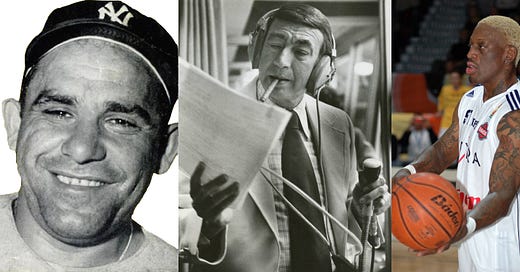

The world of sports is full of those kinds of characters, such as Yogi Berra, Dizzy Dean, Bill “Spaceman” Lee, and Tug McGraw in baseball, as well as John Madden, Howard Cosell, “Dandy” Don Meredith, Deion Sanders, Brett Favre, and Chad “Ochocinco” Johnson in football , to name just a few. And we can’t forget Dennis Rodman (basketball’s chief representative), or the erstwhile pugilist/butterfly imitator Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali). Those are some characters from “my day.” You may be thinking of more modern characters, but it seems to me that, as in so many things (here’s my inner Curmudgeon showing itself again), this is another area where “they don’t make ‘em like they used to.”

So, after that diversion, let’s get back to the core of our discussion: How is “character” to be defined?

WHAT IS CHARACTER?

According to an online source, character is “the mental and moral qualities distinctive to an individual.”

In other words, based on that definition, everybody has character, whether it be good, bad, or mediocre. “Character” is thus more-or-less synonymous with “personality”: everybody has it, even the worst and the blandest of people. Those with the most distinctive or unconventional personalities are those we refer to as “characters.”

But what I’m talking about here is good, or high, character – a person’s “moral or ethical quality.” Another way to describe a person of high character is to call him or her a person of integrity. So, to determine whether sports truly builds that kind of character, or integrity, we must ask (and answer) the question, Are the actions of athletes in harmony with accepted moral and ethical behavior?

If sports builds character, then it should be evident that athletes exhibit greater “character” than non-athletes do. Or stated and viewed somewhat differently: People should improve in their character once they get involved with athletics – a person’s character being enhanced as a result of participating in sports.

So let’s see if that is true. Let’s take note of the character of athletes. Do they exhibit high character in their actions and attitudes? Let us be clear that we are not considering physical attributes as being part of a person’s character, that is to say such things as running faster, jumping higher, etc. These abilities can obviously be enhanced through the bodily training that playing sports provides – but they don’t necessarily make someone a better person.

What, specifically, then, are we looking for? What would indicate elevated moral and ethical standards?

One way to know what to look for would be to first identify the opposite. In football, there is a penalty called “Unsportsmanlike conduct.” Which actions cause that flag to be tossed? Among other things: Trying to injure another player, taunting an opponent, or preventing the other team from getting the ball back in a timely fashion once a play has concluded. In basketball, “technicals” are assessed for flagrant fouls, and can even result in the player being ejected from the game. Ejections seem to occur more often in baseball than in other sports. Perhaps this is because baseball cannot penalize a team by changing the distance to the outfield walls (as football effectively changes the distance to the goal line by penalizing the guilty team half the distance to the goal line, 5, 10, 15 or more yards), nor do the rules of baseball allow the batter a chance to toss the ball up in the air and try to hit it over the wall (unlike basketball, where fouled players are allowed to shoot “free throws” while not pressured by defenders).

So what prompts such fouls and penalties (unsportsmanlike conduct and technicals and the like) to be called and punishments to be meted out are actions that are outrageously unfair or mean-spirited -- things like intentionally trying to harm another player (for example, a pitcher aiming at a batter’s head with the ball, or a defender in football making helmet-to-helmet contact, or trying to take a player out at the knees when tackling him, or in basketball when someone tries to take an opposing player’s legs out from under him while he goes up for a shot or a rebound). Serious penalties and fouls are also incurred for assaulting an official, or deliberately cheating in some way (by delaying the game, or tripping an opponent, going overboard in trash-talking, and the like).

The opposite of engaging in “unsportsmanlike” behavior is to be sportsmanlike – to be fair and above-board and to treat ones opponent, and the sport itself, with respect. Related to that is another common expression we’ve all heard (in addition to the phrase “Sports builds character”), namely, “It’s not whether you win or lose, but how you play the game.”

The opposite of that is the phrase, “Winning is everything.” A win-at-all costs attitude can lead to cheating, deliberately trying to injure other players (especially by targeting star players and trying to “take them out”), and other unethical behavior.

What do we see, then, in actuality, often times? Unfortunately, we sometimes see those very things: Cheating, intentionally injuring opposing players, and faking injuries. Less common but not unheard of are gambling, and even “throwing” games out of various motivations (usually involving money).

It’s easy to simply assert that such things occur in sports. How about some specifics?

In 2007, the New England Patriots were discovered spying on a rival. For the details, see Spygate.

Worse yet was “Bountygate” in which the New Orleans Saints were paying players bonuses to injure opposing players. This occurred between 2009 and 2011. You can be read about that here.

The Patriots were back to cheating in 2014, when they broke the rules in a playoff game. For that, see Deflategate.

And to go back a little further in time, and to a non-NFL incident, in 1912 Jim Thorpe was targeted by players on Army’s team when they played against Thorpe’s Carlisle Indian School team (coached by Glenn Scobey “Pop” Warner). Unable to stop him any other way, Army (whose players included future bigwigs Dwight Eisenhower and Omar Bradley) attempted to take Thorpe out of the game by injuring him. Even so, they failed in the attempt, and Carlisle won 27-6. Cheaters sometimes prosper, but not that time.

Lest one think football is the only major sport involved in such waywardness, in 2017 the Houston Astros (a baseball team) were caught stealing signs. You can read about it here.

What about basketball? It is an open secret that there are different rules for different players. Where a foul would be called on a rookie or a player of average name recognition or skill, refs often suffer from temporary blindness when a foul is committed by the game’s top stars. That’s on the refs, not the players -- and perhaps whoever is pressuring the refs to call the games that way. Taking refuge in “tradition” (by making the excuse that “it’s always been done that way”) is a bogus cop-out. But it’s not just the referees who are involved in unsportsmanlike/unfair conduct in basketball. It is also shameful, or silly, or a combination of both, when players “flop” (fake that they were steamrolled when they were barely grazed, throw their arms to the sky and collapse onto the court, sweeping the floor with their backsides).

Gambling and taking steroids and other PEDs (performance-enhancing drugs) are another matter, and beyond the scope of this brief article, except for this: The 1919 Chicago “Black Sox” world-series-throwing-scandel is covered in the book Eight Men Out and the movie of the same name.

Sounds pretty bleak, right? Is the assertion wrong, that sports builds character? Not necessarily, for there are plenty of examples on the other side of the ledger, too.

Yes, to be fair (or “sportsmanlike”), opposite examples are to be found, too. After all, Spygate, Bountygate, the 1919 “Black Sox” scandal and suchlike shocking events are famous partially for the very reason that they are relatively rare. Most teams don’t engage in those type of actions. Cynics would say other teams are just better at not getting caught. That might be true to some degree, but my opinion is that most teams and individual athletes would not stoop to that level. And of those that would, many are too afraid of being caught to actually try it.

One particularly noteworthy example of sportsmanship is that displayed by Harold Peter Henry “Pee Wee” Reese, a 10-time All-Star from the State of Kentucky. Reese played for the Brooklyn Dodgers during the time that Jackie Robinson was integrating baseball and, although a “Southerner,” Reese refused to be part of the problem when several of his teammates wanted to prevent Robinson from joining the team. Not only that, Reese went out of his way to welcome and befriend Robinson; he made a point of showing support for his teammate. One particular incident is depicted in the movie “42,” where team captain Reese approached Robinson during warm-ups (with many fans in the stands), put his arm around Robinson, and spoke to him in a confiding manner. By doing this, Reese was clearly indicating where he stood to the crowd (many of whom had been heckling Robinson). This show of solidarity has been called “Baseball’s finest moment.”

Note: “Pee Wee” Reese was no midget. He was 5’10”, which was the average height for a man of his generation in the United States. He got the nickname “Pee Wee” from his expertise at marbles as a kid.Exhibit Two: Dorrel Norman Elvert “Whitey” Herzog was white, Satchel Paige was black, and they played on the same minor league team for awhile (although Satchel was twice as old as Whitey at the time). Paige was quite possibly the greatest pitcher of all time (but due to “the color line,” he didn’t begin his major league career until he was 42 years old, when most pitchers have “had their day” and hung up their mitts for good). Paige and Herzog (probably sagely, Paige called Herzog “Wild Child” rather than “Whitey”) had a somewhat similar relationship as did Robinson and Reese.

Exhibit Three: Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi also deserves a special nod. With Lombardi serving as both Head Coach and GM (General Manager, whose role it is to draft and make trades for the players he wants on the team), the Packers had more black players than other teams did at the time (1960s). Not only that, when Lombardi found out that certain establishments in town were not allowing his black players entrance, he visited those places personally and let them know that if his black players were not welcome, their establishments would be made off-limits to the entire team (resulting in loss of revenue and prestige for the businesses). As a result of Lombardi’s unequivocal stand, the racist proprietors reversed course and welcomed all players.

HOW SPORTS CAN MAKE US BETTER PEOPLE

Based on what we see in the world of sports and its practitioners, there are positive life lessons to be learned from sports, just a few of which were briefly recounted above, but only those willing to really hear these lessons and get the sense of them take them to heart and put them into practice.

According to this article, “Sports helps an individual much more than in the physical aspects alone. It builds character, teaches and develops strategic thinking, analytical thinking, leadership skills, goal setting and risk taking, just to name a few.”

So the writer of that piece begins his list of the positive effects of athletics by repeating the belief that “sports builds character”; then he gets into some specifics about traits that are learned or honed through sports. I do not deny or refute these.

We have examined how sports can improve race relations, most specifically in the close friendship which grew between white Kentuckian “Pee Wee” Reese and Jackie Robinson. Reese had very little contact with black people prior to meeting Robinson. And that is probably true of many of us: if not for sports, our friendships would have for the most part been pretty much limited to the people we had most in common with – those who looked like us, shared the same types of experiences and culture. Sports brings people of all sorts together. Even if you’re just a spectator, not a participant, how can you ignore the fact that “your” team would not be as good if they were not racially diverse?

For example, blacks who play or are fans of basketball see that there actually are white men who can jump – or at least make up for their relative lack of “ups” in other ways – such as Bill Walton, Pete Maravich, John Stockton, Steve Nash, Bob Cousy, Jerry West, Steve Kerr, etc.

Which white football fan would think his team would be better off without its black players? Which baseball fan would think his team would be fine without its Hispanic players? Or its white players? Or its black players? In the NBA , even Europeans and Asians have made inroads. It takes a village to raise a child; it takes the entire world to build a basketball league.

When you play sports -- even more so than when simply watching, or “spectating” -- the importance and need for a diverse team should quickly become obvious to even those with challenged observation skills. Getting to know one another, being literally on the same team, and striving for the same goal with people of various backgrounds and ethnicities should lead to not mere grudging acceptance but an open-armed welcome. Appreciating one another’s talents, skills, abilities, heart, and individuality or personality (character), comes with the territory of participating in team sports.

Sports teaches you important life lessons – or can teach them to you, if you let it.

In addition to inclusivity, some other things sports will instruct you in, even if only subtly or indirectly, can be thought of as the three Rs. No, not Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic (which are not even three Rs to begin with), but Rules, Roles, and Responsibilities.

RULES

In sports, there must be rules, otherwise all is chaos and a recipe for futility. In baseball, you get three strikes, and you must touch each base before scoring a run. In football, you cannot cross the line of scrimmage prior to the offense starting the play. In football and basketball, you cannot step out of bounds. In basketball, you cannot stop dribbling the ball, and then begin dribbling it again. In all of these sports, you cannot have more players on the field at one time than a specified number (9 for baseball, 11 for football, 5 for basketball). Adhering to rules maintains a framework of fairness and equal opportunity.

Rules that we learn playing sports help prepare us for life in general, which also imposes certain rules upon us. We may not always like the rules we must adhere to, but as long as they apply to everyone, and are enforced equally, we usually learn to at least live with them, if not appreciate their purpose and overall benefit. An example of this in sports is strike zones in baseball. Every umpire has their own strike zone, peculiar to themselves. Pitchers on both teams are usually more-or-less okay with that, as long as the umpire is consistent in his application of his own personal interpretation of the strike zone. They may not be overjoyed with the umpire’s particular take on what is a strike and what is not, but as long as he applies the same strike zone to both pitchers/teams, they are willing to live with it.

Playing within the rules without having a conniption fit is something that some never really learn, though. I recall playing sports in school, where heated arguments often broke out over whether somebody had stepped out of bounds, was safe or out, or was or was not fouled. This is where refs and umpires can help matters some, of course. But typically when playing during recess or P.E. (or “Gym class,” as some call it), we refereed ourselves, and it was usually the one who launched the most pyrotechnic and vitriolic temper tantrum while channeling his inner Bobby Knight or Billy Martin who ended up getting his way (amidst the shaking heads and rolling eyes of the other participants in the game).

Did those hotly arguing their case and frothing at the mouth believe they were in the right? Sometimes they did, yes. But what can be deduced from the fact that people seem to always argue that they, or their team, were the ones who did not commit the foul, or that their opponent did commit the foul or penalty? I don’t think I ever saw anybody argue that he was out when someone on the other team was saying he was safe, or admitting that he had actually swung at the ball and missed when two strikes were on him, rather than asserting that he had not “gone around” or “broken his wrist.” Who has ever argued that they themselves had stepped out of bounds at the 10-yard line or at mid-court, and so their touchdown or field goal should not count?

Unfortunately, this self-bias that is acquired or accentuated by some when playing sports carries through to discolor the rest of their life, and they never see themselves as the guilty party. They always see themselves as the victim, who is being set upon by the world around him. They see only their side of things, no matter what, and seem predisposed to never be able to see things from the perspective of the other side, or in a disinterested (which is not the same thing as uninterested) way.

And if somebody acquires this “my team right or wrong” or “me right or wrong” mindset, where does it end? What can it lead to?

That’s a rhetorical question; “an exercise left to the reader.”

To be truly sportsmanlike, an athlete should want the right call to be made, whether it favors them and their team or not. Win the game if you can, sure, but fairly, and with the other team at full strength, if you have anything to do with it. Then you can truly be proud that you won. Two teams that played with that spirit would garner the genuine respect and appreciation of the other -- win, lose, or tie.

Ask yourself: Who do you really want on the other side of the field or court – someone you can abuse and take advantage of (or tries to do that to you), or someone you can respect and consider a worthy opponent, and who feels the same about you and your team?

ROLES

In sports, we learn that each player has a role. A pitcher does not have the responsibility of catching balls hit way over his head into the outfield. The outfielder does not have to be able to throw a curve ball or a slider. A quarterback does not need to be able to get off a block and tackle a running back trying to run by him. Nor is the defensive lineman expected to be able to spin out of a sack and throw a spiral on the run, across his body. Shaquille O’Neal could not have done Kobe Bryant’s job. Kobe Bryant could not have done Shaquille O’Neal’s job. I don’t know much about soccer or hockey, but I’m fairly certain that most goalies would not excel at the non-goalie positions, and vice versa. And in Tiddlywinks, the Tiddlers wouldn’t do as Winkers, and the Winkers can’t tiddle worth beans.

Do the realizations which we arrive at when playing sports – that we can’t do it all, and cannot fill every role -- prepare us for life? It certainly does. Having absorbed that lesson, we more easily adapt to a world in which we must recognize our place, and determine wherein our skills lie – what we can do well, and also what we cannot do as well as some others can. Perhaps our preference is to do one thing, but we are really better suited for something else. We might be “serviceable” (or “okay”) at something, but others can do the job or fulfill the role or assignment better than we can. Will we allow the better-suited to fulfill that role, without whining and moaning and trying to undermine their efforts? And perhaps even be magnanimous enough to recommend them for the job, to back them up and “campaign” for them, so to speak?

Just as not everybody can be, or should be, the pitcher, the quarterback, the point guard, or for that matter the right fielder, nose tackle, or power forward, the same is true in life. Find your niche and fill it, for the good of all. If somebody else can do a certain job better than you, admit it, and support them.

When this lesson is not learned, you end up with the always-irritating, friction-inducing “Too many chiefs and not enough firefighters” syndrome.

On the other hand, when the lesson is learned, people realize their own limitations and can “move on” with life, making the most of their individual strengths in the circumstances in which they find themselves. Here’s a guy who never could quite grasp the fact that he was not suited to be “the hero” in a particular situation:

RESPONSIBILITIES

Sports teaches you that, in your assigned role, you have certain responsibilities. When you’re the first baseman, for example, your responsibility is to have your foot on the bag and catch the ball when it is thrown to you as a runner is making his way down the first base line. It is also your responsibility to hold the runner on first base when he may have stealing second base in mind, and to be ready for the throw over from the pitcher; to effectively carry out the “pickle” if the runner gets stuck between first and second; to catch any grounders or line drives hit in your direction, etc. All of us are probably aware that the same can be said of any position in sports: they all have their own unique set of responsibilities. You cannot, and should not, try to fulfill somebody else’s role. If it’s “up in the air” (no pun intended) as to who should handle a specific responsibility, such as when a fly ball or a pop-up is hit between two or more players, one of the players will call it (“I’ve got it!” or “Mine!”), and it’s the role of the others to get out of the way and not interfere with that player – to back him up, though, in case the ball is dropped or muffed.

I know that the Green Bay Packers teach their players to do “their 1/11th” while they are on the field. They are instructed (coached) to not to try to do somebody else’s job, because then their assignment is being neglected. Each of the 11 players must do their job, carry out their assignment. If they do, every “base,” so to speak, is covered, and all should go well. Otherwise, a person failing to do their job (falling down, either literally or figuratively) can be the difference between stopping a play for little or no gain and letting the other team score a touchdown – which could possibly end up being the deciding score in the game.

Respect for one’s own responsibilities, and respect for others and their responsibilities, is a key element of playing as a unit, as a team. And it is teamwork that wins games, not a bunch of hot dogs all clamoring for the mustard at the same time. This is true not just on the field or on the court. It is true at work, at home, at school, or just about anywhere you happen to be.

WHAT DOES SPORTS TEACH THOSE WHO ARE RECEPTIVE TO BEING TAUGHT?

So, to wrap up (no tackling pun intended), does playing sports build character? Yes. It can, anyway. But whether it actually does in the case of individuals depends mainly on that individual. It depends on whether the lessons that sports conveys are understood, processed, and applied by that individual or not. Playing sports does not guarantee that a person will be molded into a fine, upstanding citizen. It does not make a bad person a good person. After all, Jackie Robinson was treated badly by many of his fellow athletes, some of whom went so far as to deliberately injure him.

Not all learn to accept and play by the rules. Instead, some try to bend, fold, spindle, manipulate, evade, or ignore them.

And some people never realize that their role should be a subordinate one, at least in certain situations. Instead, they always feel the need to assert themselves as “alpha dogs” in what they consider to be a “dog eat dog world.”

As far as learning about responsibility, some try to usurp the responsibilities that rightly belong to others (thereby displaying arrogance and selfishness) and/or shirk their own responsibilities (showing sluggishness and cowardice).

THE FINAL VERDICT

In a nutshell, then, playing sports can build character, but only for those who are receptive to the lessons sports can convey and are willing to be molded into a better version of themselves. For those who accept the adage, “It’s not whether you win or lose, but how you play the game” they – and all others involved – will be true winners, regardless of what the numbers on the scoreboard may say at the end of any given contest.

The other option is to end up being the subject of another old adage, namely “Nobody likes a sore loser.”

Clay Shannon is the author of the book “Rebel With A Cause: Mark Twain’s Hidden Memoirs”