The Mysteries of History (April 18 Edition)

Luther Stands Firm; Revere and Dawes Ride for the Brand; Frisco Earthquake

NOTE: If you detect a slight-to-moderate change in my writing style herein recently, part of the reason, at least, is that I want to make sure that my writings cannot legitimately be suspected as being AI-generated. No robot can write the stuff I do! — partly because of my use of neologisms (made-up, or new, words) and partly because of my quirky comparisons and overall tendency to be a little wacky and zany.

And who else invokes Twain as much as I do?

“The way it is now, the asylums can hold the sane people, but if we tried to shut up the insane we should run out of building materials.”—Mark Twain

1521 — Martin Luther Refuses to Be Bullied By the Church

public domain image from wikimedia commons

You would be forgiven to think that the Diet of Worms was a new-age get-skinny-quick scheme, but the “Diet” was actually a meeting Martin Luther (1483-1546) was summoned to where he was called on the (figurative) carpet for his writings criticizing church doctrine. The church functionaries threatened Luther, demanding that he recant. They wanted him to say, in effect, “My bad” and walk back his comments. He refused to do so.

And, by the way, the “Worms” presumably to be feasted on were not earth churners that some use as fish bait; Worms is, rather, a city in southwest Germany.

Luther had based his writings on his reading and understanding of the Bible, rejecting Catholic church tradition and practice. A professor of biblical interpretation at the University of Wittenberg, Luther railed against the church’s practice of selling forgiveness (“indulgences”) and other unjust, unscriptural, and illogical practices.

The Catholic church had already excommunicated Luther for his whistleblowing. They wanted him to recant, cap in hand, and plead for mercy. Instead, he remained defiant, saying, “My conscience is captive to the word of God! To go against conscience is neither right nor safe. I therefore cannot, and I will not recant! Here I stand. I can do no other.”

As powerful as the Catholic church was (is), though, not everyone was against Luther; he had friends and supporters in high places who kept him safe from the church hierarchy’s clutches.

The Lutheran church came about as a result of Luther’s exposures of Catholic malfeasance. Sadly, though, the Lutheran church too eventually became more and more like what it started out opposing.

Questions: At the start of World War 2, Germany was approximately 50% Catholic and 50% Lutheran. What % of Germans are now active in either religion? Why the fall-off? In what ways do modern-day Catholicism and Lutheranism differ? What are the different “synods” of Lutheranism, and why do they exist? If Martin Luther were alive today, do you think he would be a Lutheran? Would he rebel against the modern church? What book did Luther translate from Latin into German?

1775 — Revere, Dawes, and Prescott Warn and Rally the Minutemen

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Everybody knows about silversmith Paul Revere’s (1734-1818) “midnight ride” to warn about the British coming to attack the Americans, but he was not the only one to ride that night on that mission. William Dawes (1745-1799) was another midnight rider and partner of Revere’s. Perhaps Revere is more famous because his name sounds so much better than William Dawes. That may have been why Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) wrote the poem “Paul Revere’s Ride” rather than “William Dawes Bestride” or “Revere and Dawes Never Paused.”

The British had a plan to kidnap the rabble-rousers Samuel Adams (1722-1803) and John Hancock (1736 or 1737-1793) at Lexington, and confiscate the American armory at Concord (both in Massachusetts; Concord was seven miles further down the road from Lexington).

These plans were known by some American Patriots, and so Revere and Dawes waited for a signal that the British had begun their march and in which direction they would be traveling (see image below). Revere and Dawes then galloped (well, their horses did, actually) to warn the Patriots of the advancing redcoats. Revere and Dawes took separate routes, in case one of them was detained along the way.

The two then converged in Lexington at about the same time, and jointly warned Adams and Hancock. Revere and Dawes then lit out for Concord, along with a friend they came across on their way there, Samuel Prescott (1751-1777). Revere was captured, and Dawes lost his horse, but Prescott continued on to Concord to spread the message.

It may be interesting to some that the surname Revere is the anglicized version of Rivoire. Paul’s father, Apollos Rivoire (1702-1754), also a silversmith (and a Huguenot), was born in France.

The following is what I wrote about the Battles of Lexington and Concord in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

“These are times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.”—Thomas Paine

“Our contest is not only whether we ourselves shall be free, but whether there shall be left to mankind an asylum on earth for civil and religious liberty.”—Samuel Adams

“Small islands not capable of protecting themselves are the proper objects for kingdoms to take under their care; but there is something very absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island. In no instance hath nature made the satellite larger than its primary planet, and as England and America, with respect to each other, reverses the common order of nature, it is evident they belong to different systems: England to Europe, America to itself.”—Thomas Paine

Ten years after the fiasco of the Stamp Act, the British were still trying to micro-manage their American colonists. On March 30th of this year, The British Parliament passed an act forbidding its North American colonies to trade with any nations other than Britain. This continued bullying didn’t sit well with many of the colonists.

Britain was nervous over the impudent and surly mood of many of these Americans. The British forces, in a move to disarm the unruly locals, set out to seize caches of weapons at armories maintained by volunteer American militias, called Minutemen, near Boston in the towns of Lexington and Con cord, Massachusetts. They also hoped to capture Sam Adams and John Han cock, whom they considered “rebel” ringleaders.

Near Lexington, the Minutemen had apparently only intended to present a symbolic resistance. The Minutemen realized that they were outnumbered and outclassed by the regular British soldiers, and were not even barring the Concord road, but rather were deployed on the road’s sides. The Minutemen were, in fact, withdrawing when a shot rang out. Who fired it, and whether it was purposeful or accidental, is unknown. There had apparently been no order to fire. That shot unleashed a volley of fire from both sides.

The end result was that in skirmishes in both Lexington and Concord, about 100 colonists were killed. However, the British ultimately lost around 250 of the 700 men who had been deployed on the mission. Some of these were killed on the battlefield, but many more were victims of American snip ers as they marched back to Boston. The Americans had taken to heart the lessons of le petite guerre, the Indians’ wilderness battle tactics which had ear lier been eagerly adopted by the Colonial Rangers.

Many men, mostly from the countryside (most colonists were rural dwell ers) now joined the ragtag Colonial army. Some had no guns, but brought along what they did have: sickles and scythes.

another public domain image from wikimedia commons

Questions: If Rivoire had not been anglicized to Revere, do you think H. Wads Longfellow (as Mark Twain once referred to him) would have taken a different route with his poem about Revere’s ride? Had you been living in Massachusetts in 1775, would you have been a Royalist or a Patriot? Would you be of the same opinion as to where your loyalties would have lain had the British put down the Revolution and you were now living in a British protectorate? Are you familiar with other Longfellow poems, such as The Arrow and the Song? Do you know how this rhyme ends: “You’re a poet, but you don’t know it…”

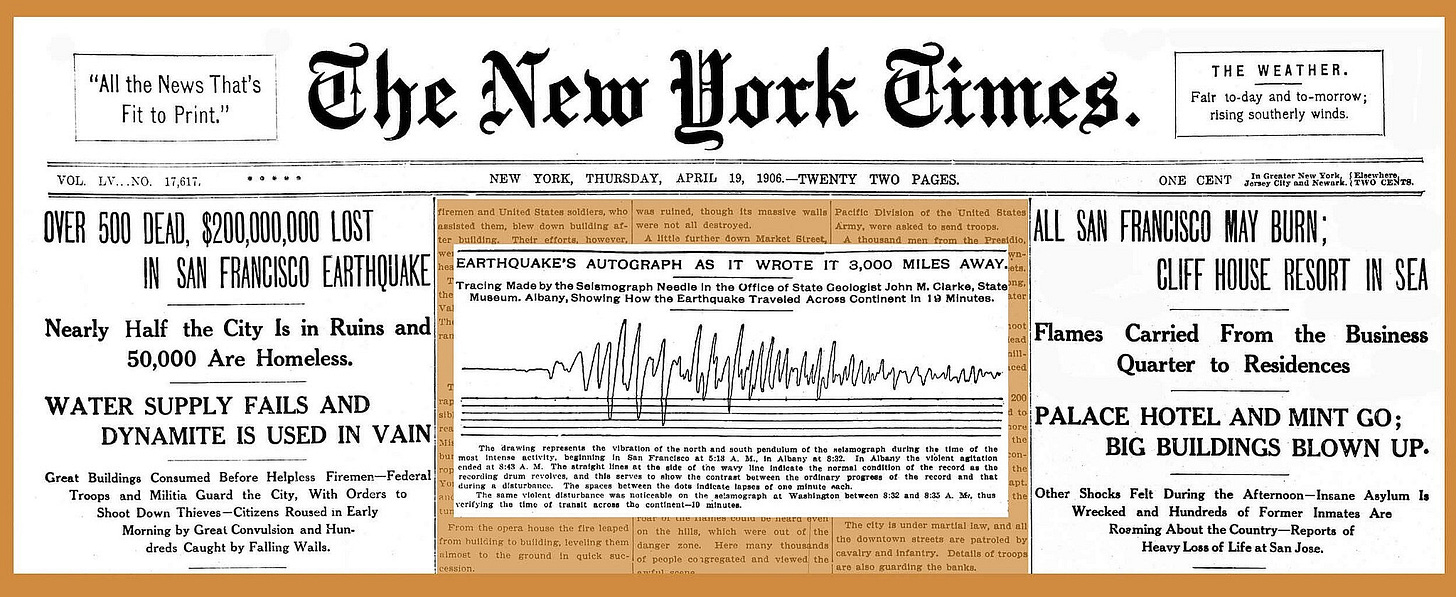

1906 — The Big One Hits San Francisco

public domain image from wikimedia commons

There have been many earthquakes in San Francisco, but the worst one, called the Great San Francisco Earthquake, occurred on this date in 1906.

Early in the morning on this date in that year (5:13 am to be precise), the populace was jolted awake by an approximately 8.0-on-the-Richter-scale trembler. Buildings toppled, three thousand people died, and the shaking was felt from southern Oregon to Los Angeles.

Many fires broke out, but they were inextinguishable due to the water mains having been broken up by the quake. It took five days to get the fires under control.

The following is what I wrote about the Great San Francisco Earthquake in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

“Talk about Mt. Vesuvius and Pompeii, this surely beats it all.”—Frederick Collins, co-owner of a women’s clothing store that burned in the 1906 San Francisco fire

One of the most devastating earthquakes in history shook northern California’s Bay Area less than a month following Girlie’s birth and the wedding of Lizzie and Harry Kollenborn. At 5:12 a.m. on April 18th, San Franciscans experienced a series of very destructive earthquakes.

While northern California had experienced major earthquakes before, such as one in 1865 that Mark Twain had been on hand for, this one was much more “special.” Since more than one third of the 1.5 million residents of the state lived within seventy-five miles of San Francisco, it was felt by a high per centage of Californians. Remote Trinity County lies two hundred miles north of the “City by the Bay,” and so was well away from the densely populated part of the state (and still is).

The rearranging of the landscape struck so suddenly and violently that hundreds of people were buried underneath rubble while still lying in their beds. Within two minutes, the earth returned to rest. The destruction wasn’t yet over, though.

Besides the devastation and death dealt by the earthquake itself, there were upwards of sixty separate fires that broke out as a result of the quake. Firemen, as was the case during the great Chicago fire of 1871, were unable to douse the flames, as no water was available—the water mains had broken. After first unsuccessfully attempting to quell the fire with sewage, they dynamited sections of the city in an attempt to halt the spread of the blaze. Some victims trapped in the rubble begged soldiers (who were on the scene to enforce martial law and shoot even suspected looters on sight) to kill them, preferring instant death by bullet to the slow roasting they would suffer when the fires reached them.

Although the number of total deaths from the disaster is disputed, the official record of seven hundred is considered by most today to be significantly lower than the actual count—there were probably three or four times that many killed. Additionally, several thousand were injured, and 225,000 left homeless.

Charles Murdock, who had lived in Humboldt County as a youth but was a San Franciscan at the time of the quake, describes it in his autobiography “A Backward Glance at Eighty,” written in 1921:

The earthquake and fire of April, 1906, many San Franciscans would gladly forget; but as they faced the fact, so they need not shrink from the memory. It was a never to be effaced experience of man’s littleness and helplessness, leaving a changed conscious ness and a new attitude. Being aroused from deep sleep to find the solid earth wrenched and shaken beneath you, structures displaced, chimneys shorn from their bases, water shut off, railway tracks distorted, and new shocks recurring, induces terror that no imagination can compass. After breakfasting on an egg cooked by the heat from an alcohol lamp, I went to rescue the little I could from my office, and saw the resistless approaching fire shortly consume it…Every person going up Market Street stopped to throw a few bricks from the street to make possible a way for vehicles. For miles desolation reigned. In the unburned districts bread-lines marked the absolute leveling. Bankers and beggars were one.

Although they also suffered immediate property damage, the aftermath of the earthquake was not wholly unwelcomed by the timber-rich area around Humboldt and Trinity counties. The rebuilding that was necessary proved to be an economic boon to the lumber industry of California’s north coast.

Questions: Why were there so many more deaths from earthquakes a century ago than today (similar-size quakes in similarly-densely-populated areas)? Have you ever experienced an earthquake? If so, how scared were you (on a scale of -17 to 11, with -17 meaning you were as cool as a cucumber and 11 meaning you were yipping and skipping and you forgot your name, rank, and serial number)?

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.