The Mysteries of History (April 22 Edition)

Oklahoma Land Grab; McCarthy's Delusions; Pat Tillman's Sacrifice

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” — Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana, 1905

1889 — Oklahoma Boomers and Sooners

image generated using Bing Image Creator

The following is what I wrote about the Oklahoma Land Rush in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

“Each was full of panic, thievery, cheating, heartbreaks, unbelievable hard ships.”—Ernie Pyle, referring to the Oklahoma land rushes

“Do not move back a boundary of long ago, which your forefathers have made.”—Proverbs 22:28

“We have first raised a dust and then complain we cannot see.”—Bishop Berkeley

On March 2nd, 1889, Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Bill, which proclaimed that unassigned lands were now in the public domain. This led the way to manic fiascoes such as the Oklahoma Land Rush.

* * *

The Indians who had been displaced from more desirable areas had been herded into Oklahoma and told that this new country would be theirs forever. They wouldn’t be bothered again. They could settle and put down roots. Before long, though Euro-Americans decided they wanted Indian Territory for themselves after all.

The next step in the Indians’ disenfranchisement was having their “permanent home” divided in two, with the western half of it becoming Oklahoma Territory, and the eastern half remaining Indian Territory. Not content with that, the whites later annexed Indian Territory, swallowing it whole. To sum up, the Indians were first forced to leave their homes elsewhere and settle in Indian Territory, then had their land there halved, and ultimately had most of it taken away completely.

Making their dispossession from their new home (Northeastern Oklahoma is still referred to as the “Cherokee Ozarks”) even more tragic is how the dis placed Indians had intrepidly soldiered on, and had made for themselves a home there. In his book “Killing the White Man’s Indian: Reinventing Native Americans at the End of the Twentieth Century,” Fergus M. Bordewich wrote:

When the Cherokees set out upon the Trail of Tears, they largely marched out of the unrelenting tragic mythology that most Americans perceive as modern Indian his tory. But they did not, of course, disappear. With characteristic determination, after a few years of factional strife, they rebuilt the nation there in the foothills of the Ozarks. By the late 1840s, the tribe was enjoying a golden era of progress that far surpassed the provincial life of their closest white neighbors in frontier Arkansas. Political institutions were reestablished, and churches, missions, and improvement societies of all sorts thrived. Protestant seminaries were established for both women and men. Temperance meetings flourished all over the nation. The Cherokee public schools became the first free, compulsory, coeducational system west of the Mississippi. Tahlequah merchants, wheelrights, and blacksmiths prospered serving Forty-niners on their way to the California goldfields.

Two million acres in the newly acquired eastern half of the Territory were made available for homesteading on April 22nd of this year. Actually, there were eleven land openings in Oklahoma between 1889 and 1906. Half of present-day Oklahoma was colonized by these openings to white homestead ers.

Despite this opportunity for free land, Carleton Shannon opted for Cali fornia rather than join the mad rush to Oklahoma.

The opening of the Oklahoma Territory for settlement was supposed to be fair, but, as usual, some scofflaws found a way to get around the legal requirements ments. The book Moments in Oklahoma History—People, Places, Things, and Events by Bonnie Speer reports on these shenanigans, as well as on some enterprising and colorful individuals:

During the run of 1889, any man or single woman 21 years of age or older could stake a 160-acre claim, but had to live on it at least six months of the year. Chick asaw resident R.M. Graham, his two sons, and a hired man laid claim to an entire section of land [townships were thirty-six square miles and were divided up into thirty-six sections; one section was 640 acres] near Lexington. Four months later when Graham’s daughter turned 21, the hired man relinquished his claim to her. Graham then built a house at the point where the four claims came together. Each claimant had a bedroom on his or her own land, thus fulfilling the letter of the law…

It was a most ambitious land grab. Before the opening of the Cherokee Outlet in 1893, a pair of enterprising brothers ran cattle north of what is now Mooreland in northwestern Oklahoma. The two ranchers hired 150 extra hands to make the run and to stake a claim. On each claim these cowboys erected a four-foot square “house,” then relinquished the claim to the brothers. After all, nowhere in the rules for the run did the government state the size of the needed improvement. A town was later established and named in honor of the Quinlan brothers…

Henry Ives, who came to Guthrie on the day of the Run of 1889, was shocked at the lack of sanitary conditions in the new tent town. Deciding to do something about it, he dug a deep hole on his lot, then securing a quantity of leafy limbs from Cotton wood Creek, he planted them upright around the hole, and erected a sign: “Rest Room, 10 cents.” Business was good, but rivals eventually forced him to lower his prices to five cents. Even so, when his enterprise was no longer needed, he had earned enough money to open a harness repair shop.

“Button Mary” became a familiar figure in Guthrie after the run. She arrived on the day of the opening and set up her tent beside the railroad track. One of the town’s more enterprising citizens, each morning at sunrise, she left her camp and made her rounds through the busy tent city with needle and thread in hand. Each time she met a manwithamissing button on his clothing, she sewed one on then requested a dime for her work. If he paid her, all was well and good, but if he didn’t he received a sharp jab with the needle.

In some cases, the very people whose duty it was to facilitate the fair han dling of the matter were among the scoundrels who cheated their way to land ownership. For example, some of the deputies on hand in 1889, posted near the lots to preserve order, handed in their resignations as a pistol shot signaled to the waiting multitude of men on horses and in trains that the race for choice parcels was on. They thus had a head start over everyone else, as they were already “on the spot” and were able to stake lots they had chosen in advance. These were the “Sooners.” Some of them paid for their cleverness with their lives.

The trains were jam-packed with hopeful homesteaders. There were not only people in the trains, but on top and underneath of them as well, hanging by the handrails, and even sitting on the cowcatchers. Why the frantic rush to be first? There were not enough lots for all comers to Guthrie and Oklahoma City—to the quickest and strongest went the spoils.

Fifty years after the fact, on April 24, 1939, traveling newspaper correspon dent Ernie Pyle described the scene:

Suppose we are sitting by the railroad track at Guthrie, Oklahoma, a little before noon on April 22, 1889…

Pack sacks fly out the train windows. Hurtling humans follow them. Half a dozen dash for a lot they’ve just spied. And instead of driving stakes, they drive their fists into each other’s faces. A late-thinker jumps off and stakes the very lot they’re fighting for.

We won’t forget the woman for a long time. She stands on the roof of a boxcar run ning at full speed, and throws over her rolled-up tent and haversack. And then in one wild plunge she projects herself into thin air, bent for a Guthrie lot or hell won’t have it. She turns five somersaults in the air with her Mother Hubbard flying, five more after she hits the ground, and winds up against the fence with only one broken leg.

As the train finally stops, the massed thousands pile off in a choking melee. Every man for himself, and no quarter asked. One great fat man tries to crawl through the window. He’s so big he gets stuck. Another man comes past, openly lifts his wallet, and goes on. Dozens see it, and no one cares.

Men are held up at gunpoint and robbed without a sound or word, so crushing is the mob. As quickly as the throng breaks loose from itself, it spreads out over the eighty acres in a bewildered chasing of itself. A blind man’s bluff, hunting for lots. You don’t know how far to run, where to stop, whether to turn right or left. A greedy and pan icky afternoon.

Fifteen long trains come in from the north before sundown. In five hours the population of Guthrie leaps from two hundred to fifteen thousand.

Counting those who went to other townsites, and those racing over the prairies, no fewer than a hundred thousand people entered the “unassigned lands” that afternoon of April 22, 1889.

Long before dark Guthrie was taken, and a tent city had sprung up. There was yell ing and shooting that night, but little harm was done. The newcomers were too busy. Even before nightfall, frame houses had arisen. Trains bore in more lumber and brick and hardware. The transformation of Guthrie was remarkable. You can hardly believe what you read about it.

In one month there was hardly a tent left in Guthrie. Within three-and-a-half months Guthrie had streets, parks, a water-works, an electric-light plant, and brick buildings by the score. Lots that cost nothing on April 22 were selling for five thou sand dollars only sixty days later.

At the end of those one hundred days there were in Guthrie five banks, fifteen hotels, ninety-seven restaurants and boarding-houses, four gun stores, twenty-three laun dries, forty-seven lumberyards, four brickyards, seventeen hardware stores, thirteen bakeries, forty dry-goods stores, twenty-seven drugstores, fifty groceries, three daily newspapers, and two churches—all in a town of fifteen thousand.

What happened in Guthrie happened in Oklahoma City, on a smaller scale. For years the two cities were to fight for supremacy. Guthrie lost the last stand in 1913, when the state capital was moved to Oklahoma City.

Today Guthrie has fewer people than it had on that first night in 1889. And Oklahoma City has grown to two hundred thousand. Which proves you never know when to jump off a train.

Pyle also wrote about the run for the six million acres of land known as the Cherokee Outlet, or the Cherokee Strip (which was two hundred miles long and fifty miles wide, and formed the northern slab of Oklahoma):

The start of that wild race across the prairies must have been one of the greatest spectacles in American history. One who saw it said there rose from that line a roar like a mighty torrent—a roar of voices fifty miles long. He said it was a roar so far reaching and prolonged that his very sense of hearing was stunned and his capacity for thought paralyzed. He said he had heard the roar of sixty batteries of artillery in the Civil War, and experienced the sound of the Federal yell and rah coming up from fifty thousand soldiers’ throats, and listened to the fiercest thunder as it rattled among the lonely pines of the Black Hills—but never had he heard a cry so peculiar, a roar of such subdued fierceness as that which rose from the prairies to the skies on that fateful September 16. …

The cowboys on broncs quickly took the lead. And then, far out ahead, they stopped and set fire to the grass, to throw up a wall of fire against those behind. But the grim home-hunters plunged on through. Many horses were so badly burned they had to be destroyed. Others fell into ravines, wrecking wagons, hurting men and horses alike.

One man rode his horse to death, and when it dropped he sat on its side, rifle across his knee, claiming the land his beloved horse had fallen on. Another man had toughened his mustang by riding it full-speed eighteen miles a day for two weeks before hand. He led the race toward the town of Enid, twenty miles northward. But he, too, fell victim to the grass fires and gullies, and his willing mount came to its broken finish a mile from Enid. He had to shoot the mustang, but he ran the last mile on foot, and was the first one into town.

The only reason the Indians had been given the land previously (it was Indian Territory prior to becoming Oklahoma) was that the area was considered unsuitable for white people to live on. In other words, it was initially viewed the leftovers or dregs of the land, and was meant to serve as an Indian ghetto where the natives would be “out of sight, out of mind.” When the whites decided they wanted it after all, they became “Indian givers” and grabbed it back.

From 1817, the Apaches and the six Cs (Cherokee, Cheyenne, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Commanche, and Creek) had lived there.

Like moviegoers lining up for a long-awaited blockbuster film, 50,000 landlusters waited in tent cities to take off, hell-bent-for-leather, at high noon on this date in 1889. They were called “Boomers”; those who “jumped the gun” and chased down a tract of land before the noon gun sounded came to be known as “Sooners.”

Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither were the Oklahoma towns of Guthrie, Kingfisher, Norman, nor Oklahoma City, but they all got a jumpstart on this date in 1889.

Those who had cheated and entered the plots early (the “Sooners”) were sued, and these law cases took up a lot of time and money for years. Thus, subsequent land grabs (as more of Oklahoma was opened up for white settlement, even the parts that been assigned to specific tribes rather than the wide-open, unassigned area opened in 1889) were accomplished by lottery rather than on a “first come, first served” basis. By 1905, whites owned most of Oklahoma. In 1907, it became the 46th State.

Questions: If you had been alive in 1889, would you have been tempted to join the Boomers? If so, would you have been tempted to be a “Sooner”? What acts of violence were visited upon Sooners by those who had waited and “missed out”? Where are the “Cherokee Ozarks”? Have you heard the song Never Been to Spain by Three Dog Night?

1954 — Conspiracy Theorist Vs. The U.S. Army

public domain image from wikimedia commons

If Senator Joe McCarthy is reading the room in the photo above, his facial expression hides it well, as nobody seems convinced or receptive to his message.

The following is what I wrote about McCarthy’s mad ramblings in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

“Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness…Have you no decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?”—Joseph Welch, lawyer for the U.S. Army, addressing Senator Joseph McCarthy

“He that is excavating a pit will fall into the same, and he that is rolling away a stone—back to him it will return.”—Proverbs 26:27

Joe McCarthy went too far in 1954 when he accused the U.S. Army of being riddled with communists. To President Dwight D. Eisenhower—a career military man—this allegation seemed fishy, to say the least. Eisenhower ordered an investigation into McCarthy’s shenanigans.

From April to June, the “Army/McCarthy Hearings” were broadcast on television. As McCarthy didn’t have a leg to stand on, he was exposed as a vicious fraud. At the culmination of the hearings, McCarthy was censured by the Senate, of which he was a member. He succumbed to alcoholism and died three years later, in 1957, at the age of forty-nine

Apparently McCarthy had a beef with the army because a former colleague of his was drafted, and was not given the special treatment McCarthy requested. He bit off more than he could chew, though, when he attacked the army on the television, making himself look foolish and even insane. In addition, he provoked the wrath of President Eisenhower.

On being called on the carpet by the Army’s attorney, as quoted above, McCarthy had to grin and bear it as the audience erupted, cheering and applauding Welch’s takedown of the sleazy slanderer. At the end of the year, his fellow Senators voted to censure him for his brash and brazen bullying and bullshitting.

Questions: Are there any modern-day Joseph McCarthys? Are there any modern-day Joseph Welches?

2004 — Pat Tillman Killed By Friendly Fire

public domain images from wikimedia commons

Pat Tillman was a professional football player, and a good one. He gave up millions of dollars to retire (presumably intended to be temporarily) from the NFL and join the military following 9/11. Two-and-a-half years later, at the age of 27, Tillman was killed by “friendly fire” in Afghanistan on this date in 2004.

As it is wont to do, the government at first attempted to keep the real cause of Tillman’s death from the public.

Questions: Have you read Jon Krakauer’s book Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman?

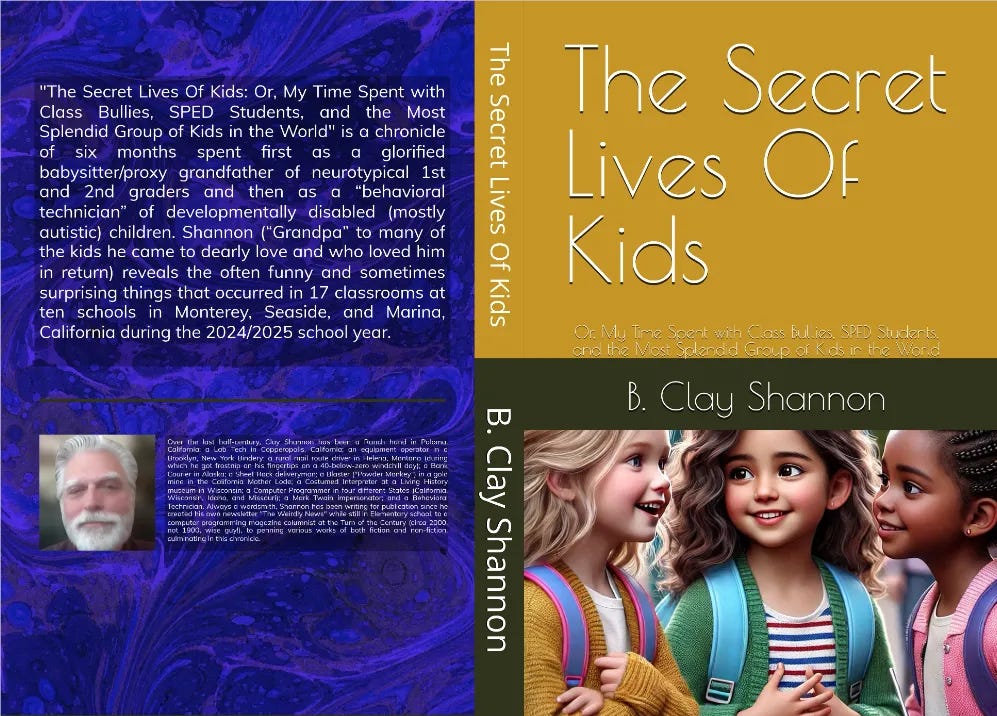

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.