The Mysteries of History (April 29 Edition)

Joan of Arc Relief; Dachau Releases; Rodney King Riots

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” — Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana, 1905

“He is free to evade reality, he is free to unfocus his mind and stumble blindly down any road he pleases, but not free to avoid the abyss he refuses to see.” — Alice O’Connor, 1961

1429 — Joan of Arc Leads Reinforcements to Orléans

public domain image from wikimedia commons

French farm girl Joan of Arc (1412-1431, Jeanne d'Arc to the French) rallied the troops to the North-Central French city of Orléans where, during the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), the British had been holding sway for six months.

Not only did the teenager think she was on a holy mission (she had reportedly heard voices telling her to help the French King-to-be, Charles, defeat the British), the King himself was at least not totally disinclined to believe her, supplying her with a force of soldiers to rush to the aid of the beleaguered residents of Orléans. By means of some nifty military maneuvers, Joan and her men were able to expel the British from Orléans within a week-and-a-half.

That was just the beginning of Joan’s exploits, as she and her entourage traveled from there to other battles, similarly winning surprising victories over the stunned British.

However, a little over a year after the Siege of Orléans, Joan was captured, delivered to the British, found guilty by them of being a heretic and a witch, and was then burned at the stake as punishment for those crimes.

Questions: How was a teenage country girl able to rouse and lead groups of soldiers into battle? Have you read Mark Twain’s book on Joan of Arc? Why did he at first publish it anonymously?

1945 — Prisoners of Dachau Liberated

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Dachau was Nazi Germany’s first concentration camp, set up just five weeks after Hitler came to power in 1933. On this date in 1945, twelve years later, the U.S. Army arrived, shutting down the camp and liberating its prisoners.

At first, Dachau was mostly populated with Germans: political prisoners, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Roma (“Gypsies”), homosexuals, and repeat offenders. Not until five years later, in 1938, did Jewish people become the most heavily represented demographic.

To the Nazis, Dachau was the “model” camp, where concentration camp guards were trained in the “right” way to go about their ghastly and grisly business.

As if animal vivisection were not evil enough, the Nazis even conducted medical experiments on live inmates, killing and maiming hundreds of them in the process.

Reading the writing on the wall (that they were about to fall), most of the German officers, mad scientists, and professional sadists absquatulated prior to the Americans arriving; so when the Americans did appear, there were only a few Nazi guards left to “watch the store,” and thus the battle that ensued was brief.

Although massive numbers had been killed (9,000 of the bodies not yet disposed of), there were still 30,000 survivors, alive but not too well.

Questions: How did the American soldiers respond to what they saw at Dachau? What were the citizens of the city of Dachau forced to do? Did all of the Germans captured go to trial?

1992 — Riots Ensue When Rodney King’s Assailants Are Exonerated

public domain images from wikimedia commons

The assault on Rodney King (1965-2012) in March of 1991 was not a matter of conjecture or “he said, they said” — it was captured on videotape for all the world to see. So when the uniformed bullies were found innocent of the charges against them on this day in 1992, riots broke out around the city.

The rioting was senseless, of course, and the end result was 60 people killed and many more injured. The anger many in the community felt over the miscarriage of justice was indeed understandable, but the way it was expressed was illogical and simply an imitation of the depraved acts of the three policemen who mercilessly beat King (a fourth was present, their Captain, who did not participate directly in the beating but also obviously at least allowed it).

Besides the beatings administered seemingly randomly to passing motorists and people “in the wrong place at the wrong time” by the rioters, there was also looting and arson galore.

The anger on the part of the police officers toward King on the night of his arrest and beating was also not unwarranted, as the inebriated King had led them on a wild and dangerous chase through L.A. County and then initially resisted arrest. But in their case, too (and they should have been “the adults in the room”), their manner of expressing their anger was over the top, to say the least.

The riots were the greatest civil unrest in the U.S. in the 20th Century; it took three days, the National Guard, and riot police to finally quell them.

A measure of justice was eventually handed down, though — if only the rioters hadn’t been such hotheads, much pain and agony would have been spared: In 1993, Captain Stacey Koon and Officer Laurence Powell were found guilty by the DOJ for violating King’s civil rights, and were each sentenced to 2.5 years in jail. The other two officers were acquitted.

The following is what I wrote about the Rodney King incident in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

Although many law enforcement personnel present at the trial—including the CHP officers who started the chase—condemned their overwhelming use of force, all four officers (Stacey Koon, Theodore Briseno, Timothy Wind, and Lawrence Powell) captured on videotape beating Rodney King were acquitted by an all-white jury in arch-”conservative” Simi Valley, which is located forty miles northwest of Los Angeles. A crowd of at least 300 outside the courtroom erupted in anger on hearing the verdicts. They yelled “guilty” as the plaintiffs came out of the courthouse and chased the officers to their cars with rocks.

Many observers were completely dumbfounded by the outcome of the trial. Yale University law professor Drew Days, who had been an assistant U.S. attorney general, articulated the views of many when he said: “It is astounding that anybody could look at that film and not conclude that those police officers were violating someone’s civil rights.”

Similarly, Benjamin Hooks, executive director of the NAACP, said, “Given the evidence, it is difficult to see how the jurors will ever live with their consciences.” And L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley, in a remark that was criticized by some as incendiary, was shocked: “I was speechless when I heard that verdict. Today this jury told the world that what we saw with our own eyes is not a crime.”

Yet even President George H.W. Bush did not mince words. He said that he, his wife, and his children were stunned by the verdict. He agreed with many others quoted above when he said, “Viewed from outside the trial, it was hard to understand how the verdict could possibly square with the video.” What about Rodney King’s reaction? The book “Understanding the Riots: Los Angeles Before and After the Rodney King Case,” compiled by the staff of the Los Angeles Times (whose building was also the target of rioters during the unrest), reported it this way:

As for Rodney King himself, he retreated to the solitude of his bedroom, shaking and speechless. He had watched the verdicts on television. Stunned, he had reached for a pack of Marlboro Lights. “He wasn’t talking in clear sentences,” said one friend. “It suddenly was like he had no idea who he was or what time it was or where he was. He would start to make sense, and then 10 seconds later he couldn’t even tell you what room he was in. The lights were off, the television turned down low. On the screen, the officers who had beaten King were hugging and smiling, free men. Through the door, King’s occasional screams could be heard. “Why? Why? Why?” he groaned. “Why are they beating me again?”

What is often referred to as the “justice system” is perhaps better described as the “legal system.” Is justice the aim of its practitioners? Or simply enforcing the letter of the law? The penal codes are black and white. Justice is another concept altogether, and any who would really try to uphold it would be sticking their neck out. Once again the ubiquitous and multipurpose acronym CYA stamps itself on events, an acronym which, among other things, stands for California Youth Authority.

The jury’s practically inconceivable decision triggered three days of rioting over a fifty-square-mile swath of Los Angeles. Sympathy riots broke out in other cities, including Atlanta, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Miami, New York, Seattle, and even the relatively small cities of Madison, Wisconsin; Providence, Rhode Island; and Hartford, Connecticut, one-time home of anti-slavery authors Mark Twain (“The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”) and Harriet Beecher Stowe (“Uncle Tom’s Cabin”). Hundreds of fires were set and millions of dollars worth of goods were looted. Fifty-four people were killed, over two thousand wounded, $700 million of property was damaged, and more than thirteen thousand arrests were made. This was the worst urban dis order in the U.S. since the 1863 New York City draft riots that took place during the Civil War.

Parking lot attendant Adey Behre said, “It’s terrible what they’ve done. I’m from Ethiopia, where they have a lot of problems. But I’ve never seen any thing like this.”

The outrage of many from the African-American Community in Los Angeles manifested itself on April 29th with a chaotic cacophony of mayhem directed against, it seemed, any non-black person. In some cases, even light skinned blacks who appeared Caucasian by mobs were targeted.

Of course, not all African-Americans were involved in the lawlessness. In some cases, they came to the aid of those the crowds were pummeling. One example of this was actor and author Gregory Alan-Williams, who saved the life of a Japanese stranger, Takao Hirata, as he was being beaten to death by a rabble of bloodthirsty rioters.

After wrenching him away from the clutches of the murderous mob, Alan Williams asked Takao his name and, due to the man’s impaired speech (which came out sounding slurred or heavily accented), thought he was a recent immigrant. Gregory welcomed Takao to America. Hirata responded with a wry grin. In actuality, the Japanese man was born in America-in a government internment camp during World War II, in which his family had been placed due to their ethnicity.

The reason for Hirata’s unclear speech? Members of the crowd had not only smashed him in the face with their fists, but had viciously broken bottles against his face.

Alan-Williams was not the only good Samaritan on the scene from the African-American community: A middle-aged man was also on the scene, protecting Hirata by holding back some of the attackers. After Alan-Williams had escorted Hirata away from the worst area of the trouble spot, another black man came to the rescue and drove Hirata to the hospital.

Additionally, pummeled white truck driver Reginald Denny was taken to the hospital by five black men. Denny had been dragged from his truck, beaten, kicked, and had his own fire extinguisher bashed against his skull. Similar to the Rodney King beating, it was seen by millions on television—the difference being that Denny’s beating was broadcast live, as it was happening—the police unable to come to his assistance.

That was also a conundrum to many. Nargas Nadjati, a resident of the hardest hit part of the city, wondered aloud: “How could it take them so long? They are so fast to send troops to the other side of the world. Why can’t they save our city?”

Although Denny’s face was covered in blood and his eyes were swollen shut, he somehow managed to climb back into his truck and began to drive slowly away. He was helped by some good Samaritans who at first hung on alongside his truck and guided him with steering instructions, and then took over the driving, pulling his truck into the hospital in the nick of time—he suffered a seizure on arrival at the hospital, and doctors said had he arrived any later he would have died.

Another hero was L.A. Times reporter John Mitchell, who saved a Viet namese refugee from the wrath of an angry mob.

What started as a riot in response to the injustice in the Rodney King case seemed to morph into a combination poverty riot (many stores were looted) and a race riot, wreaking revenge not only on whites, but also on Asians. Many of the latter were targeted, either personally or via their businesses, partly as a result of lingering animosity over the shooting death of African American girl Latasha Harlins by a Korean grocer in 1991 (the store clerk had argued with the 15-year-old over a bottle of orange juice). As the four police men in the Rodney King case had been, Soon Ja Du was inexplicably acquitted.

Los Angeles Times reporter Josh Meyer wrote of some looting that he witnessed:

One woman zoomed up to the front of the building in a late model Seville, a wild look in here eyes and a grin on her face. She jumped out of her car without rolling up the windows, leaving her screaming infant unattended. Then, the well-dressed, professional-looking woman sprinted into the store for her share. Inside the market, there was pandemonium.

As I scribbled notes furiously, one looter, dragging what appeared to be a small copying machine, tapped me on the shoulder and said calmly, “I know you’re a reporter, but can you help me drag this outside?” I said no. He went on dragging.

As far as monetary damage to businesses went (from vandalism and looting), the ethnic groups who suffered the most were Koreans and—perhaps surprisingly, African-Americans. During the Watts Riots/Rebellion of 1965, black businesspeople had tried to ward off destruction of their own shops by posting “Soul Brother” signs in their store windows. This time, the signs read “Black Owned.” Nevertheless, many of them were still targeted. The reason some rioters hurt themselves or members of their own race? One person com pared it to a person becoming so angry that he strikes out in uncontrolled rage and frustration and punches a wall—hurting his own hand in the process.

Another, perhaps more convoluted, psychological hypothesis asserts that such self-destructive behavior is a result of self-loathing brought on by an internalizing of the message behind the verdicts—that they are a lesser people, unworthy of justice.

Regardless of the psychology behind it all, Rodney King was not reveling in the rabid rabble’s reckless abandon. The afore-quoted book “Understanding the Riots” tells of what happened on May 1st:

On the third day, Rodney King came out of hiding. He emerged from his lawyer’s office in Beverly Hills to be engulfed by a throng of 100 reporters. City Hall had called minutes earlier: King wouldn’t say or do anything to make the situation worse, would he? The mayor’s staff wanted to know. Nervous and barely audible, his voice lost at times to the blast of helicopter rotors overhead, King delivered a halt ing plea for peace that, in its rambling, elliptical, tragic quality, became one of the more memorable moments in the Los Angeles riots.

“Can we get along?” King asked, almost begging. “Can we stop making it horrible for the older people and the kids?…We’ve got enough smog here in Los Angeles, let alone to deal with the setting of these fires and things. It’s just not right. It’s not right, and it’s not going to change anything. We’ll get our justice. They’ve won the battle, but they haven’t won the war. We will have our day in court, and that’s all we want…I’m neutral. I love everybody. I love people of color…I’m not like they’re…making me out to be. “We’ve got to quit.

We’ve got to quit…I can understand the first upset in for the first two hours after the verdict, but to go on, to keep going on like this, and to see a secu rity guard shot on the ground, it’s just not right. It’s just not right because those peo ple will never go home to their families again. And I mean, please, we can get along here. We all can get along. We’ve just got to, just got to. We’re all stuck here for a while…Let’s try to work it out. Let’s try to work it out.”

President Bush also did his part to defuse the situation. The book just quoted adds this:

Bush also announced that a federal grand jury had already issued subpoenas as part of an accelerated Justice Department investigation into whether the beating of Rodney King violated federal civil rights laws. White House aides described the unusual disclosure as an attempt by Bush to soothe the destructive anger sparked by the not guilty verdicts.

A certain degree of justice was eventually obtained. The next year, two of the officers were found guilty on federal civil rights charges.

Questions: Were you alive during the Rodney King beating and the trial of the policemen? If so, what do you remember of it? If you had been in L.A. at the time, what would have been your response? Does it make any sense to protest needless violence with even more senseless violence? Do you think the DOJ would have charged the police officers had the incident not become such a cause cé·lè·bre?

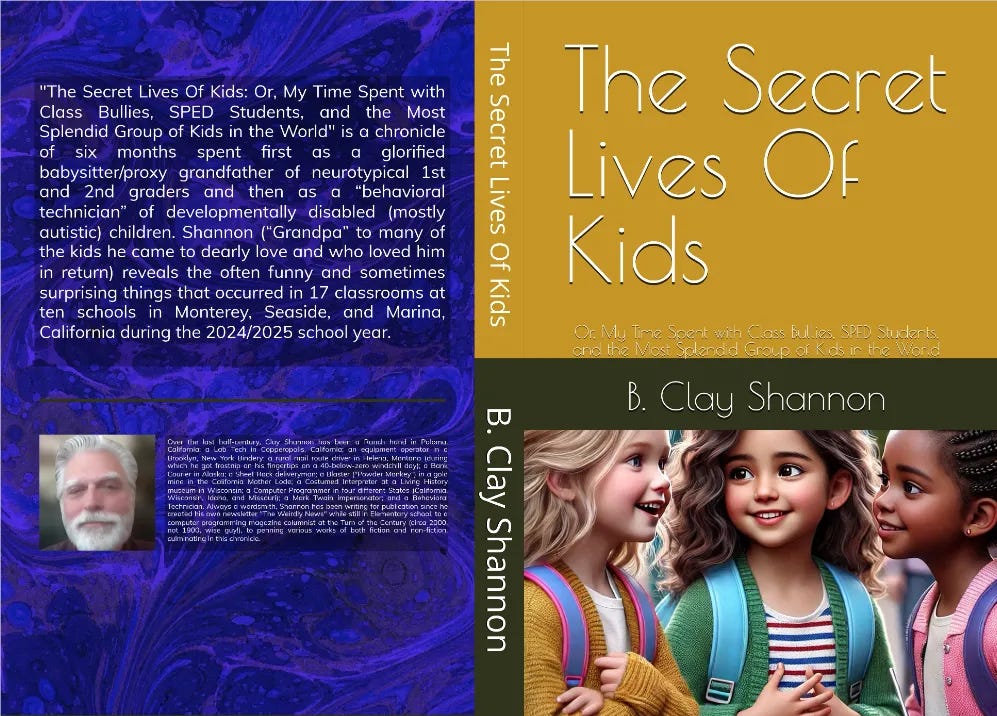

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.