The Mysteries of History (April 3 Edition)

PdL in Florida; Pirates Sanctioned by Congress; Pony Express; Richmond Soldiers Absquatulate; Jesse James Killed; Marshall Plan; Unabomber Arrested

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” — Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana, 1905

1513 — Ponce de León Explores Florida, Claims it Belongs to Spain

public domain image from wikimedia commons of Martin Waldseemüllers 1513 map, with Florida at upper left

Ponce de León washed up near what is now Saint Augustine, Florida, on this date in 1513 and promptly claimed the area for Spain.

About fifty years later, Saint Augustine became (by some accounts) the first city in the U.S.

Of course, natives had lived in the region since time immemorial, so it wasn’t really logical for Ponce to claim it somehow now magically belonged to his fatherland of Spain. Then again, if the rumors are true, he was apparently quite the gullible fellow, as he believed in a “fountain of youth” and searched for it there. By this time at the latest, de León had to learn to get used to disappointment.

On returning to Florida later in an attempt to start a Spanish colony there, he was attacked by indigenous peoples, and suffered a wound from an arrow. From there he absquatulated to Cuba, where he died in his mid-40s in Havana as a result of the wound, possibly from poison applied to the tip of the arrow he was shot with.

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Questions: If the fountain of youth was real, and Ponce had found it and quaffed its elixir, would he still have died from the poison arrow? What island nation had de León been the Governor of?

1776 — Pirates Sanctioned By Congress

public domain image from wikimedia commons

In their fight against the British, America gave privateers (“Pirates”) the go-ahead to attack British vessels. John Hancock, the President of the Continental Congress, authorized such as a means of acquiring the money needed to fund a strong Navy in opposition to the British. Goods taken from the enemy ships were divided 50/50 between the pirates and the American government.

In effect, the privateers/pirates became de facto members of the American military, except that their payment came on a commission basis.

Questions: How vital were the Pirates to the Patriot cause? How many ships did they attack over the course of the war, and how much booty did they acquire?

1860 — Pony Express Begins Its Brief Ride

image generated using Bing Image Creator

The following is what I wrote about the Pony Express in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

When considering what happened of import on the national scene in 1860, many Americans would think first of Abraham Lincoln’s victory in that year’s Presidential campaign. For others, the beginning of the Pony Express may also come to mind. For a much smaller number of people, the year 1860 may bring to mind the orchestrated wanton slaughter of Wiyot Indians that took place simultaneously at three locations near Eureka, California in the winter of that year. A common thread in these three events is the untimely demise of all the subjects: Just five years later, in 1865, Lincoln was assassinated by a former soldier and then-thespian named John Wilkes Booth; the Pony Express was dealt a death blow by the telegraph less than 20 months after the express company’s inception; and hundreds of Wiyots, many of them in the prime of life, were murdered. In fact, as can be readily deduced from Bret Harte’s quote above, many of those killed were mere infants. Another common thread that runs through these events is that the principals (Lincoln, Pony Express, Indians) are all today American icons. But there was no Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. in 1860; the Pony Express was just another enterprise, to be patronized or not, depending on your need for its services—probably most Americans of the day never heard of it; and as for the Indians? They, especially, were not treated as anything special at the time. In fact, as Dee Brown describes in detail in his book “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee,” a thirty-year period of especially brutal slaughter of the Indians began in 1860.

. . .

The Pony Express offered swift (for the times) delivery of mail along its route from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California. The “help wanted” ad for these long-distance jockeys was a beckoning call to adventure some or desperate people who could meet the following prerequisites:

WANTED: Young, skinny, wiry fellows, not over eighteen. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. Wages $25 per week.

Stated otherwise: Old fat guys, the timid, and those whose demise would cause undue heartache to various and sundry relatives need not apply. The Pony Express operated like a relay race: the riders spurred their mounts at full speed from one station to the next, where they were relieved by a fresh horse and rider, passing the mail like a baton from one man to the next. Its retinue of riders, which included William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, carried parcels just under 2,000 miles within a ten-day span—averaging upwards of two hundred miles per day! This work was performed by five hundred horses and eighty riders—forty heading east and forty heading west at any given time. In a total 650,000 miles of travel by the Pony Express riders, only one parcel was lost. In his excellent book Roughing It, Mark Twain described the phenomenon:

In a little while all interest was taken up in stretching our necks and watching for the “pony-rider”—the fleet messenger who sped across the continent from St. Joe to Sacramento, carrying letters nineteen hundred miles in eight days! Think of that for perishable horse and human flesh and blood to do! The pony-rider was usually a little bit of a man, brimful of spirit and endurance. No matter what time of the day or night his watch came on, and no matter whether it was winter or summer, raining, snowing, hailing, or sleeting, or whether his “beat” was a level straight road or a crazy trail over mountain crags and precipices, or whether it led through peaceful regions or regions that swarmed with hostile Indians, he must be always ready to leap into the saddle and be off like the wind! There was no idling-time for a pony rider on duty. He rode fifty miles without stopping, by daylight, moonlight, star light, or through the blackness of darkness—just as it happened. He rode a splendid horse that was born for a racer and fed and lodged like a gentleman; kept him at his utmost speed for ten miles, and then, as he came crashing up to the station where stood two men holding fast a fresh, impatient steed, the transfer of rider and mail bag was made in the twinkling of an eye, and away flew the eager pair and were out of sight before the spectator could get hardly the ghost of a look. Both rider and horse went “flying light.” The rider’s dress was thin, and fitted close; he wore a “round-about,” and a skull-cap, and tucked his pantaloons into his boot-tops like a race-rider. He carried no arms—he carried nothing that was not absolutely necessary, for even the postage on his literary freight was worth five dollars a letter. He got but little frivolous correspondence to carry—his bag had business letters in it, mostly. His horse was stripped of all unnecessary weight, too. He wore a little wafer of a racing-saddle, and no visible blanket. He wore light shoes, or none at all. The little flat mail-pockets strapped under the rider’s thighs would each hold about the bulk of a child’s primer. They held many and many an important business chapter and newspaper letter, but these were written on paper as airy and thin as gold-leaf, nearly, and thus bulk and weight were economized. The stage-coach traveled about a hundred to a hundred and twenty-five miles a day (twenty-four hours), the pony-rider about two hundred and fifty. There were about eighty pony-riders in the saddle all the time, night and day, stretching in a long, scattering procession from Missouri to California, forty flying eastward, and forty toward the west, and among them making four hundred gallant horses earn a stirring livelihood and see a deal of scenery every single day in the year. We had had a consuming desire, from the beginning, to see a pony-rider, but some how or other all that passed us and all that met us managed to streak by in the night, and so we heard only a whiz and a hail, and the swift phantom of the desert was gone before we could get our heads out of the windows. But now we were expecting one along every moment, and would see him in broad daylight. Presently the driver exclaims: “HERE HE COMES!” Every neck is stretched further, and every eye strained wider. Away across the endless dead level of the prairie a black speck appears against the sky, and it is plain that it moves. Well, I should think so! In a second or two it becomes a horse and rider, rising and falling, rising and falling—sweeping toward us nearer and nearer—growing more and more distinct, more and more sharply defined—nearer and still nearer, and the flutter of the hoofs comes faintly to the ear—another instant a whoop and a hurrah from our upper deck, a wave of the rider’s hand, but no reply, and man and horse burst past our excited faces, and go winging away like a belated fragment of a storm! So sudden is it all, and so like a f lash of unreal fancy, that but for the flake of white foam left quivering and perishing on a mail-sack after the vision had flashed by and disappeared, we might have doubted whether we had seen any actual horse and man at all, maybe.

This exciting and romantic endeavor was short-lived, however. Any who may have sought a long-term career with the Pony Express, which began operation April 3rd, would have been disappointed on November 21st, 1861, less than 600 days later. On that date, the Central Overland Express ceased operation, as their service was made obsolete by the invention and implementation of the telegraph, which provided faster and less expensive delivery of messages.

Samuel Morse had invented the telegraph in 1837, but it wasn’t until 1844 that it was mature enough to be of practical use. An additional seventeen years were necessary until a coast-to-coast network of telegraph poles were completed—in 1861, twenty-four years after his invention.

On this date in 1860, Pony Express riders from both ends of their route began simultaneously: those from St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California, and those from Sacramento to Saint Joe.

Ten days and 1,800 miles later, the final rider heading west arrived in Sacramento. It took the other rider another couple of days to reach Missouri. The Pony Express riders traveled through 150 relay stations and seven States (from east to west: Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, and California).

Each rider traveled 75-100 miles before being relieved by the next rider. The horses were also changed out, and much more often: every 10-15 miles. The riders were paid approximately $25 per week, corresponding to a little less than $1,000 in 2025 — not a pittance, but not a lot considering the nature and danger of the work.

Questions: Had you been alive at the time, would you have wanted to be a Pony Express Rider? What would have been the main motivation to do it? What would have been the main argument against do it? Did any of the riders eventually become famous? What connection does Colorado Liquor License #1 have with the Pony Express?

1865 — Confederate Capital Captured

public domain image from wikimedia commons

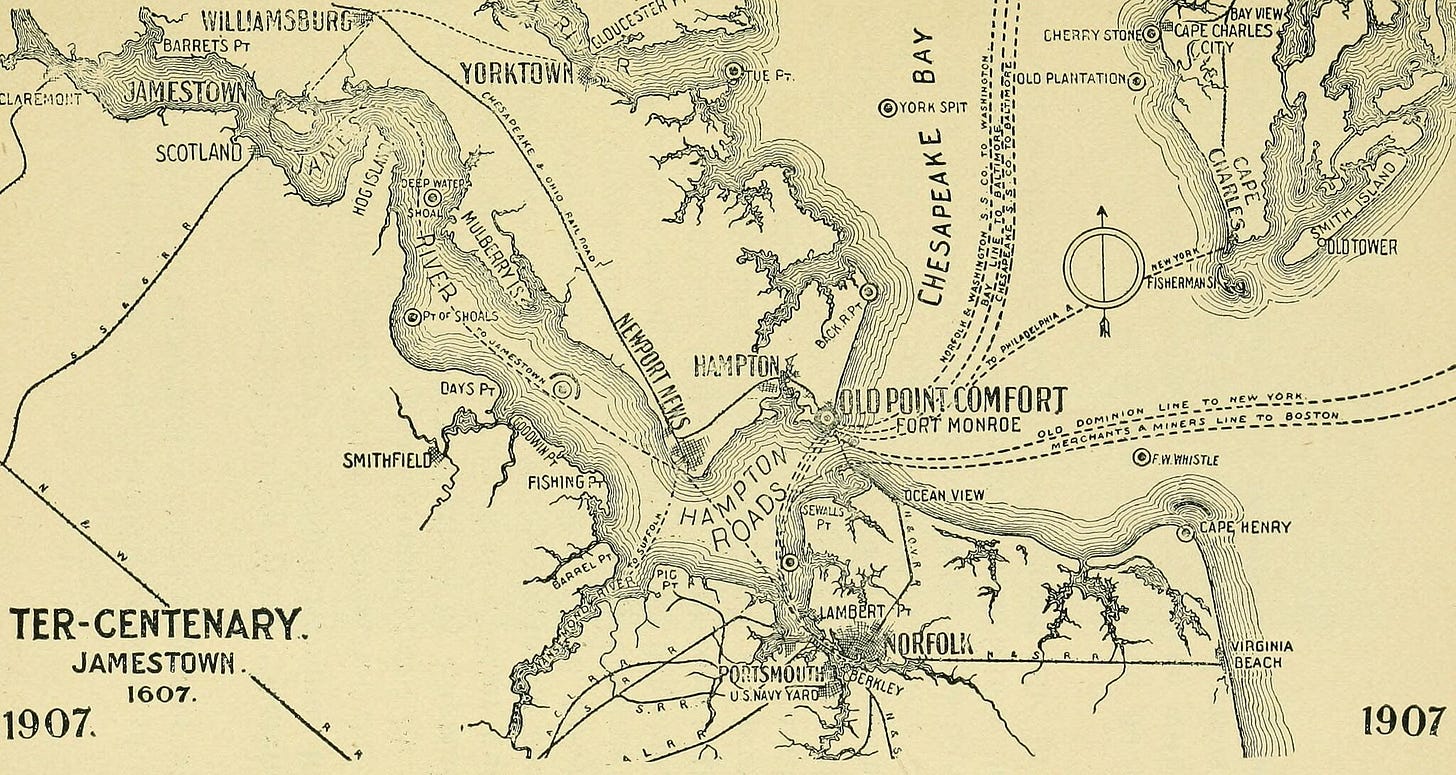

In one of the last nails in the coffin of the Confederacy, on this date in 1865 Richmond, Virginia, the Rebel capital fell to Union forces.

Reactions by the residents differed starkly, depending mostly on whether they were white or black. The politicians, along with the army, had already absquatulated, leaving the residents to welcome or be wary of the arriving Union soldiers.

Among the first men in blue to arrive were black soldiers from the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry. The next day Abraham Lincoln arrived for a visit. In just a day or two, the situation in Richmond had turned upside-down.

Questions: Was there any violence between the white and black residents of Richmond after the politicians and southern soldiers left? Where did the absquatulating pols and military personnel go — to a single destination together, or did they separate and scatter back to their homes?

1882 — Jesse James Killed While Tidying Up the House

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the Jesse James’ death in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

Jesse Woodson James was the son of a preacher and a fire-breathing confederette who egged her sons Jesse and Frank on in their iniquities. Zerelda James was proud of her offspring when they robbed, killed, and terrorized abolitionists in western Missouri. As a group, the types of men Jesse and Frank operated with were given the semi-romantic title of “Bushwhackers.” In reality, they were nothing more or less than cold-blooded, white supremacist terrorists of the worst sort.

Jesse James lost his life, not in the act of robbery, but while standing on a chair straightening a picture. Although extremely suspicious and distrustful (and justifiably so), one person Jesse really liked and trusted was Bob Ford. Bob and his brother Charley, visiting with their old partner in crime at his home in Liberty, Missouri, took advantage of the fact that Jesse had removed f irst his jacket due to the sultry weather, and then his revolver belt because he was wary of raising suspicions if somebody outside were to see that he was walking around armed inside his house. The last sound Jesse heard was one very familiar to him: the cocking of a pistol. On turning around, Jesse may have had a fraction of a second to see who held the pistol and the expression on the gunman’s face. It is said that “money talks,” and that “every man has his price.” In this instance, at least, regarding Jesse and Bob and Charley, those hackneyed maxims proved true. Many people would have liked to have seen Jesse killed in order to rid the area of a menace. The Ford brothers, though, didn’t perform this execution impelled by a desire for justice or with the public welfare in mind. Pure and simple, they were after the $10,000 reward—the equivalent of over $100,000 today. The Fords did eventually get the money, and were absolved of any guilt in Jesse’s murder. Not content with taking the reward money and quietly retir ing to a farm or ranch somewhere, the Fords toured the country demonstrat ing their feat in a sort of macabre freak show called, imaginatively enough, “How I Killed Jesse James.” As for other principals in this melodrama, Charley Ford shot himself later this year, and Jesse’s brother Frank turned himself in to Governor Crittenden; Bob Ford was murdered in Colorado in 1892. Although the Kollenborns (and the Huddlestons, and probably the Branstuders, too) were already in Missouri before the death of Jesse James, it was the demise of this feared outlaw that provided the signal that Missouri was now a civilized, safe place in which to live. The menace had been eradicated. The worst of the bushwhackers had all been either ambushed, imprisoned, or run out of the state. This opened the floodgates to more westward roamers from the eastern states.

Robert Ford didn’t kill Jesse for the money only; he was only an associate of the gang, not really a full-fledged member, and there was no love lost there. To put it euphemistically, Jesse was not Robert’s favorite guy.

Jesse’s tombstone read: “Jesse W. James, Died April 3, 1882, Aged 34 years, 6 months, 28 days, Murdered by a traitor and a coward whose name is not worthy to appear here”

Questions: How is it that the James Brothers are viewed by many as “Robin Hood” types? Who wrote the folk song “Jesse James” and what slant does it take on Bob Ford shooting Jesse James? Who was “Mr. Howard”?

1948 — Truman Supports the Marshall Plan

image generated using Bing Image Creator

The Marshall Plan, named for Secretary of State George Marshall, was a project to help rebuild Europe after World War 2 by providing them with money. President Truman signed off on it on this date in 1948, about two-and-a-half years after the war ended.

America was willing to part with its money because they felt this was a way to win hearts and minds to democracy and away from communism. Between 1948 and 1951, $13 billion (approximately equivalent to $173 billion in 2025) in aid was provided by America to the European countries who endorsed the plan. Some of the money was provided as grants (gifts) and some as loans. The nations who accepted these gifts and loans were Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and West Germany.

Questions: What would have happened to the Nations listed above had they not received assistance from the United States? Why was the United States in a position to give and lend money to these European countries? Did the lent money get repaid? If so, when? Was it a good investment? Was it a “hard sell” to the American people (whose taxes paid for it)?

1996 — Ted “Unabomber” Kaczynski Apprehended

public domain image from wikimedia commons

See the January 22nd edition of this series, specifically the article 1998 — Ted Kaczynski Fully Admits His Guilt here.

Kaczynski’s (1942-2023) preference was to buy land in the Canadian wilderness, but he settled on purchasing a little over an acre near his brother’s house in Lincoln, Montana. During his quarter of a century there, Kaczynski was mostly self-sufficient, but also worked occasional odd jobs and sometimes traveled.

Questions: What was the turning point in Kaczynski’s life that changed him from a socially awkward, geeky math professor to a domestic terrorist? What case of mistaken identity was involved in one of Kaczynski’s attacks, and what happened to the victim? When did Ted’s brother first suspect his brother was the Unabomber, and when did he report his suspicions to the authorities? What took him so long? Was anybody harmed by Ted in the interim?

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.