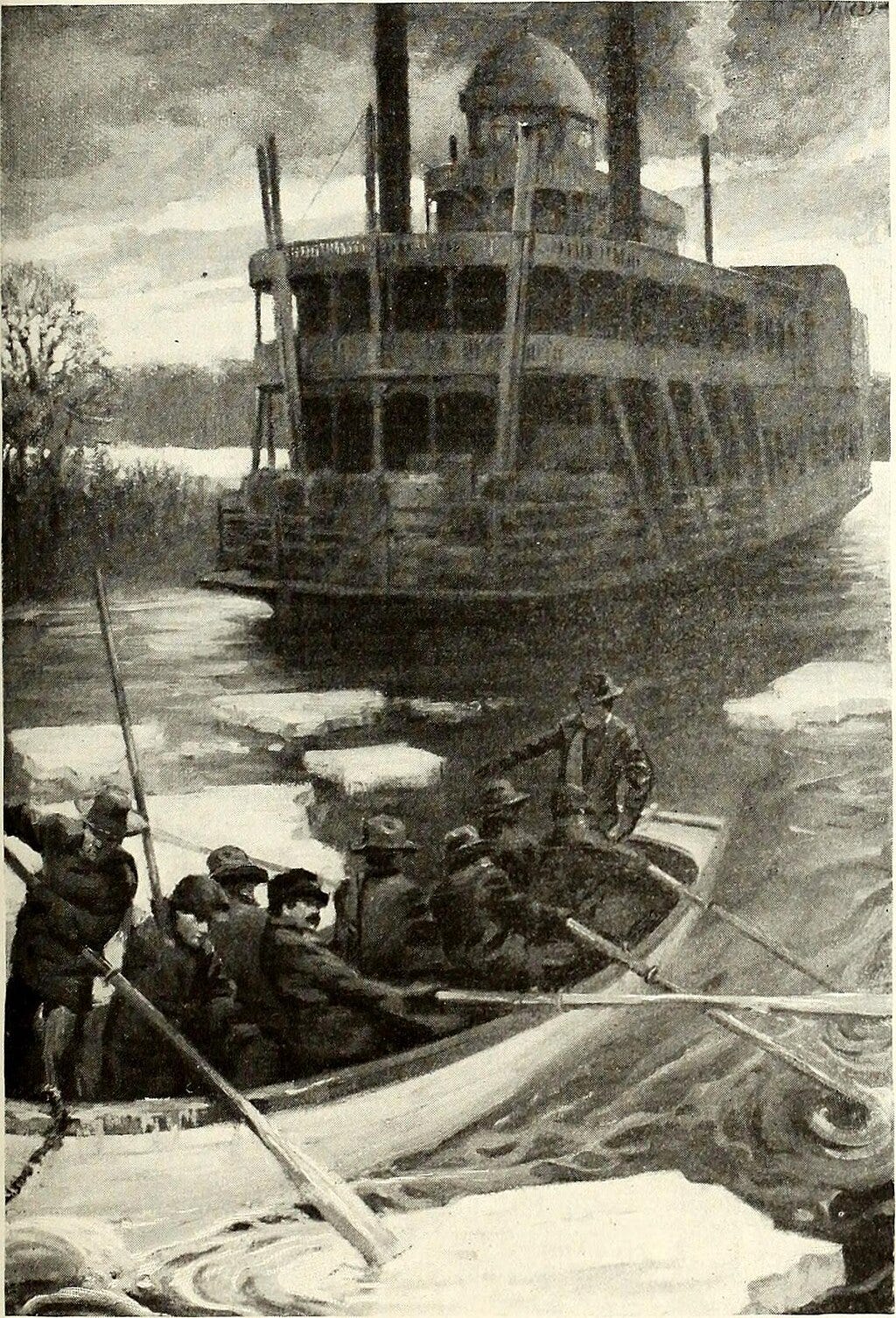

1859 — Mark Twain Gets Pilot License

public domain image from wikimedia commons

American writer Mark Twain (born Samuel L. Clemens, 1835-1910) received his steamboat pilot license on this date in 1859.

After pursuing that career for some years, Twain became a newspaper reporter in Nevada and California, and then a writer of short stories, travelogues, polemics, and novels, such as (to name just a few): The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County (short story), The Innocents Abroad (travelogue of Europe and the Holy Land), Roughing It (travelogue, mostly of Nevada (“Washoe”), California, and Hawaii), The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (novel), Life on the Mississippi (recounting his piloting days), Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (novel), A Tramp Abroad (travelogue), The Prince and the Pauper (novel), Following the Equator (travelogue), and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (novel). This just scratches the surface of Twain’s voluminous output.

Questions: Had Clemens written anything for publication at this time of his life? What event ended his career as a steamboat pilot? Where did he go from there (geographically and professionally)? Which sketch (short story) brought him nationwide fame? How many of Twain’s books have you read? Which is your favorite?

1865 — Civil War Officially Ends at Appomattox Court House

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the end of the Civil War (1861-1865) in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

The four year national nightmare symbolically and effectively ended when Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant worked out the details of Lee’s surrender at the small town of Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, on April 9th in the home of Wilmer McLaine. It could be said that the war practically began in McLaine’s front yard and ended in his parlor, as General P.G.T. Beauregard had used McLaine’s farm house as his headquarters during the First Battle of Bull Run, or Manassas, near the start of the war, and then his home was used for the meeting between Grant and Lee at Appomattox Courthouse—to which secluded region McLaine had removed in what turned out to be a futile attempt to get away from the war. As Lee noticed Grant’s military secretary, Ely Parker, a Seneca Indian, Lee remarked that it was nice to have a “real American” present. Parker responded: “We are all Americans here.” Not wanting to rub defeat in the Confederates’ faces, Grant allowed those surrendering to keep their horses, so that they could return home and commence farming. He also sent the vanquished army food, and disallowed extended celebrations among his own troops, saying that as the end of the war had made the union whole again, it was not fitting to continue to view the southerners as enemies. Some fighting continued elsewhere for a time, but Lee’s surrender of The Army of Northern Virginia following the evacuation of Richmond, the capitol of the Confederacy, made it clear it was just a matter of time before the War would come to a complete halt. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured May 11th while trying to escape across the Mississippi River, and the last confederate troops to surrender did so later that month, on the 26th. By the end of April, following William Tecumseh Sherman’s “March to the Sea,” where he overthrew and burned Atlanta and continued seaward on to Savannah, a group of die-hard Confederates surrendered near Raleigh, North Carolina. A hundred years later those environs (including the fictional Mayberry) would be portrayed on television as the most wholesome and safe of American regions.

At the end of May, a little over four years since Fort Sumter on the South Carolina coast was bombarded, the War officially came to an end. But let us now step back in time just a little and follow James Shannon and the 16th Michigan from the beginning of the year. They remained at their winter quarters for the first three months. In early April, they were engaged at Petersburg, twenty miles south of Richmond. Here Grant achieved one of the major military objectives of the war: As was the case with Cold Harbor, just north of Richmond, the capture of Petersburg paved the way for the taking of Richmond, the Confederate Capitol. It was at this juncture that Confederate President Jefferson Davis and the rest of his government fled. Following these victories surrounding Richmond, the 16th Michigan were among those who, with U.S. Grant, pursued Robert E. Lee and placed him in a position where he was forced to realize his army was fighting a lost cause, at which point Lee finally surrendered. Grant, in his memoirs (whose production and printing was engineered by Mark Twain, who saw in Grant’s autobiography a chance to do well while also doing good—make a good profit for himself while simultaneously helping out the Grant family, who it seemed would otherwise fall on hard financial times at terminally ill Grant’s death) recalled this momentous occasion thus: What General Lee’s feelings were I do not know…but my own feelings…were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly and had suffered so much…General Lee was dressed in a full uniform, which was entirely new, and was wearing a sword of considerable value…In my rough traveling suit…I must have contrasted very strangely with a man so handsomely dressed, six feet high and of faultless form…We soon fell into a conversation about old army times…Our conversation grew so pleasant that I almost forgot the object of our meeting.

Yes, Grant and Lee, like most of the generals involved on both sides, had known each other prior to the great conflict. Lee, who was married to a great granddaughter of Martha Washington and whose father, Henry Lee, had been a Revolutionary War cavalry officer nicknamed “Light Horse Harry,” had been the head of West Point. Jefferson Davis had been U.S. Secretary of War, and had been involved (as was Abe Lincoln) in the Black Hawk War. Many of the generals on both sides had fought together in the Mexican War, too. To give one example, confederate P.G.T. Beauregard and Union general George McClellan served on Winfield Scott’s staff during that campaign.

Also serving with the Confederate forces were: former U.S. President John Tyler’s grandson Ben C. Johnson; a grandson of Patrick Henry’s, who participated in Pickett’s charge; World War II General George Patton’s grandfather; and General Lewis Armistead, nephew of George Armistead. It was George Armistead who had defended Fort McHenry in Baltimore when it was being attacked by the British in 1814. The earlier Armistead asked for the production of a huge flag, one that could be easily seen by the British. Francis Scott Key, held prisoner by the British on a ship in Baltimore harbor, also saw the f lag, and was inspired to write “The Star Spangled Banner.” The Confederates viewed their government as the continuation of that of their forefathers, and likened their cause to those who had fought the Revolutionary War against Britain. In fact, the Confederates called the Civil War the “Second Revolutionary War.” James Shannon was promoted to Full Corporal on May 1st (thus, after Lee’s surrender). Later that month, his Regiment marched to Washington, D.C., arriving there on the 12th and participating in the Grand Review with the Army of the Potomac on May 23rd. George Custer led that review. In a macabre foreshadowing of future events, a newspaper report said of the marvelous horsemanship Custer displayed on that day: “It was like the charge of a Sioux chieftain.” The Regiment’s last shared experience of note took place there in Washington. In The 16th Michigan Infantry, Kim Crawford reports: Some men had been singing as darkness fell, and soon a group took out candles they had been issued that evening, and fell into line with the singers. The parade probably started by men who were fooling around more than anything else, but soon the idea took on a life of its own. Several thousand men with bayonet-candled torches formed their procession “out of pure joy,” remembered a veteran from the Third Brigade.

The cheering parade stopped at the headquarters of Generals Griffin, Bartlett, and Pearson, and those of other commanders, where the men called for speeches. This spectacle continued until their candles burned out. On June 16th, the 16th Michigan was ordered to Louisville, Kentucky (one hundred years later a member of the Kollenborn family would be a paratrooper stationed in that state, at Fort Campbell). The men of the 16th took a train to West Virginia, followed by a steamer down the Ohio River to Louisville. The Jeffersonville, Indiana on July 8th. They then returned to Michigan, arriving in Jackson on the 12th, where they waited until they were given their final pay on the 25th, after which they disbanded. Colonel Benjamin Partridge sent the men on their way with a final address: This is the hour which has served as a talisman to each of you during the last four years. The rebellion crushed out of existence, the Union one and inseparable, and yourselves enabled to return to your homes, to follow the peaceful pursuits of life. May your career in civil life be as successful as your military has been. Before parting with you, I must express my high appreciation of your merits as patriots and soldiers. You have earned and received enconiums of praise from every commander under whom you have served, and you served under those who knew too well the value of praise to bestow it unmerited. When I look around me and see the heroes of such battles as Gaines Mill, Malvern Hill, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg and the tremendous Wilderness fights, and then think of the noble spirits we lost at those places, it would seem that we were cemented to each other by something stronger than the common ties of friendship. I hope we shall always entertain this friendly feeling towards each other, and above all, let us cherish with reverence the memory of our fallen braves; and let us ever be ready to the extent of our power, to aid a dependent relative of any of those who fell in the cause of liberty, and in the ranks of our glorious organization. Afinal tally of casualties for the 16th Michigan Infantry Regiment shows a total casualty rate of 25.1%. Two hundred twenty seven of them had been killed in action, eight died in Confederate prisons, and one hundred four died from diseases. Two hundred eleven of them had been discharged for wounds during the war.

As to the morale of the Union forces at Hatcher’s Run, James McPherson wrote in For Cause and Comrades: On at least one occasion Union soldiers even sang while fighting. A brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac rode along his lines during the battle of Hatcher’s Run in February 1865 and found that “our boys were singing at the top of their lungs ‘Rally Round the Flag, Boys,’ and in the finest spirits imaginable. At the same time they were loading and firing away.

Robert E. Lee (1807-1870) came to the meeting in full regalia, including sash and sword, while Ulysses Grant (1822-1885) arrived “as he was,” in a muddy uniform. The terms of the surrender allowed the Confederate soldiers to take their horses home (something they would need for spring planting), the officers to keep their sidearms (pistols), for all of the Confederate soldiers (including officers) to be pardoned, and provided for the feeding with Union rations of those surrendering.

Lee died in 1870 at the age of 63; Grant died in 1885, also at the age of 63.

One year to the day after the surrender, Grant was stopped by Washington, D.C. police for speeding in his horse buggy. There is no record of just how fast Grant had gotten his horse to go, but he paid a fine for the infraction.

The fine apparently was not too much of a deterrent, though, as Grant was arrested for speeding two more times after that in the nation’s capital, the final time when he was serving as President, an office he held from 1869-1877.

Questions: How common is it for Southerners to give their children the name “Lee”? Although known as Ulysses S. Grant (U.S. Grant), with what first and middle name was General/President Grant born? What is the connection between Mark Twain and Ulysses Grant? What did Grant die of? What conclusion did Twain draw from the cause of Grant’s death, yet what did Grant’s doctor tell him?

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.