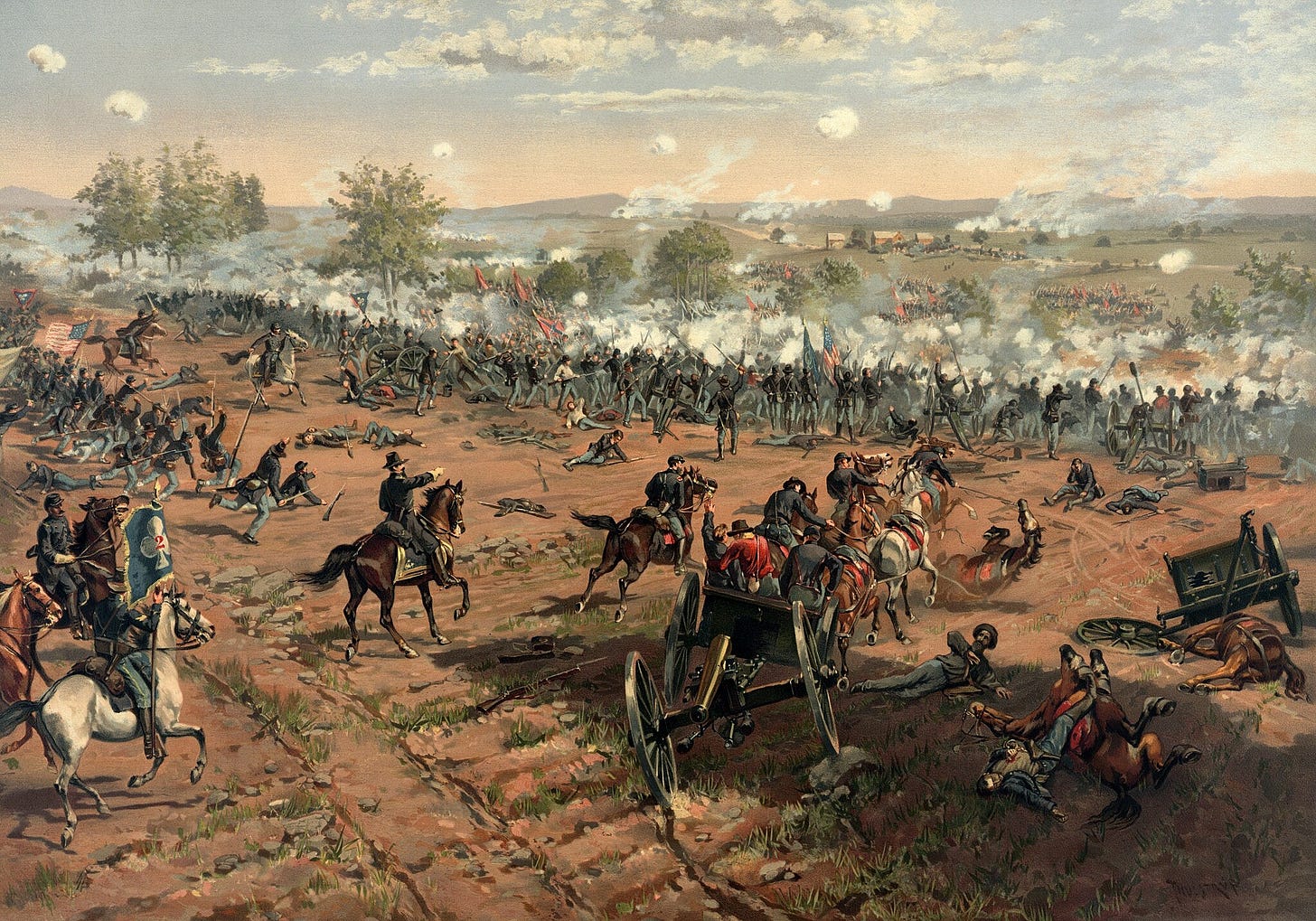

1863 — The Battle of Gettysburg

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Many historically significant battles began on this date: in 1898, the Battle of San Juan Hill in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, where Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders found fame; in 1916, the Battle of the Somme in France during World War 1; and in 1942, during World War 2, the Battle of El Alamein in North Africa.

Possibly the most significant of these, for residents of the United States, at any rate, was the three-day Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania, which Abraham Lincoln later commemorated with an eponymously-titled Address.

Robert E. Lee led the 80,000 rebels, while the Union forces, led by Meade, outnumbered them by almost 20,000. This mismatch in numbers may have been a major reason that Lee eventually felt it prudent to beat a strategic retreat and live on to fight another day.

The following is what I wrote about The Battle of Gettysburg in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

Of the 10,000 locales where Civil War battles were fought, most of them were in very small towns, rather than cities. Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, is a prime example. Chancellorsville was even less noteworthy a place—it wasn’t even a real town, just a large brick farmhouse and inn about ten miles west of Fredericksburg, the scene of the 16th Michigan’s last battle of 1862. There were scattered farms and a couple of churches and taverns in the surrounding area.

The 16th Michigan was engaged at Chancellorsville and were assigned an important role in that disastrous battle. Although a confederate victory (considered Robert E. Lee’s greatest), the 16th held the ground they were assigned though repeatedly charged by the southern forces. Edward Hill of the 16th related an exchange between General George Meade and Charles Griffin, a fellow general:

“Have you placed the regiments in position, general?” Meade demanded.

“I have,” Griffin replied.

“Are they troops on whom you can depend?” Meade asked.

“General, they are Michigan men,” Griffin responded. “But will they hold their ground?”

Meade persisted, not thinking his question had been answered.

“Yes, general. They’ll hold it against hell.”

Kim Crawford’s painstakingly researched book “The 16th Michigan” tells of what James Shannon’s experience as a member of the Brady Sharpshooters may have been in the Battle of Chancellorsville:

A short distance away at Chancellorsville, Union front lines were themselves blasted by Confederate Artillery. The Brady Sharpshooters were still posted near the Chancellor House, a building Alfred Apted referred to as “the brick hotel.” Apted’s diary tells of the “fearful fury” of the battle and that the artillery fought throughout the afternoon. “The reb loss is fully three to our one,” he estimated when he made his entry that day. “The hardest battle yet.”

Union troops in those advanced positions to the south suffered relentless Confederate artillery fire and punishing attacks. They withdrew back into the contracting Union lines. The Chancellor House itself was bombarded as the soldiers retreated.

General Griffin, who commanded the division of which the 16th Michigan was a part, was ordered to direct Union guns to keep the advancing Rebels at bay late that morning. An artillerest, Griffin asked for all the available spare cannon and uttered a vow that became one of the famous quotes of the Civil War: “I’ll make them think hell isn’t half a mile off.” His guns did so, and retreating Union troops joined the Fifth Corps and others in the defenses north of Chancellorsville.

While making a night reconnaissance, confederate leader “Stonewall” Jack son was killed by friendly fire; J.E.B. Stuart temporarily took over his command. Later in the war, Stuart was killed by George Armstrong Custer’s men.

Possibly the most famous engagement of the war, and a turning point in it, the Battle of Gettysburg was fought at the mid-point of the year. Meade on the Union side, who had recently taken over command from Hooker, and Lee for the Confederacy, plied their deadly trade and played their deadly combination of “chicken,” chess, and “King of the Hill.” Lee had invaded Pennsylvania in June and had hoped to threaten Washington and Philadelphia and put a damper on Union morale. This would be the bloodiest battle ever fought on American soil.

Gettysburg was a small Pennsylvania college town. The battle there lasted three days. The 16th Michigan was only involved the second day. The first day, they were on their way, marching all day and half the night. They only got three hours of rest before being rousted out of their sacks early on July 2nd to complete the last three miles of their hike into Gettysburg.

On arrival, the 16th realized that a huge showdown was in the making. The entire Army of the Potomac was there, having arrived at the same spot via various routes. The “visiting team,” the Confederate army, was also there, and in great numbers.

As to the “home field advantage” an army had, that is, whether they were fighting on their home turf or in country foreign to them, the difference it made could be considerable. Morale improved when the civilians they encountered were friendly, and oftentimes at least one member of the group was familiar with the territory, which intelligence often proved to be of great practical advantage.

As to having civilians on one’s side, even if only in spirit, McPherson writes in “Battle Cry of Freedom” about the Union soldiers on their way to Gettysburg:

As the army headed north into Pennsylvania, civilians along the way began to cheer them as friends instead of reviling them as foes. Their morale rose with the latitude. “Our men are three times as enthusiastic as they have been in Virginia,” wrote a Union surgeon. “The idea that Pennsylvania is invaded and that we are fighting on our own soil proper, influences them strongly. They are more determined than I have ever before seen them.”

The 16th Michigan, along with the 44th New York, the 83rd Pennsylvania, and the 20th Maine, were assigned to defend Little Round Top, a rocky bulge above the town and connected to Big Round Top by a saddle-shaped ridge. The strategic location was simultaneously sought by Hood’s Texas troops—it was a race to see who could first reach the summit. With supreme effort, Hazlett’s Battery was dragged and pushed and lifted up the side of the steep and rugged side of the mountain. The Union Army won the race, a scarce five minutes ahead of the Rebels.

Had they been delayed five minutes for whatever reason, they may have lost Little Round Top. Had they lost Little Round Top, the course of the Battle may have been different. Had the course of the Battle been different, the course of the War may have been altered.

Although the 20th Maine under Joshua Chamberlain were to play the most pivotal role in defending Little Round Top, the 16th Michigan’s Brady Sharp shooters also played a significant one. According to Crawford, the Sharp shooters were deployed across the saddle onto Big Round Top, to the left of the line of defense:

Rufus Jacklin claimed the opening shots in the fight for Little Round Top were by the skirmishers of the 16th Michigan as the Texas and Alabama troops of Gen. John Bell Hood’s division advanced, yipping the Rebel yell. “The Brady Sharpshooters firing the first shots down upon their advance columns from the Big Round Top was the signal of the attack,” Jacklin stated years later.

John Berry, whose Company A was detached along with the sharpshooters, was even more specific, though his estimation of the time was off by an hour. “We get into position into line of battle,” he recorded. “Our company with the company of sharpshooters is then sent out as skirmishers and we advance about a half a mile and find the enemy. About 3 o’clock the battle commences in earnest and a terrible engagement ensues along the whole line which last[s] until dark.”

Private Alfred Apted of the Brady Sharpshooters wrote that the enemy “started about 4 p.m., and came around the west of our lines and took position on the next extreme left of our lines.”

These directions and descriptions support Jacklin’s statement that 16th Michigan skirmishers were on the wooded slope of Big Round Top, a fact further confirmed by Capt. Walter G. Morrill, commander of Company B of the 20th Maine. Morrill and his skirmish company crossed the ground between the two hills and started to climb Big Round Top. “I immediately deployed my men as skirmishers and moved to the front and left,” Morrill wrote in his report, “ordering my men to connect on the right with the 16th Michigan Regiment skirmishers.”

The climactic moment of the battle came when Hood’s men made their charge across the open fields towards Cemetery Ridge. Climbing toward the summit, these Rebels were repelled when Chamberlain’s 20th Maine, out of ammunition, and much to the amazement of the rebels, fixed their bayonets to their muskets and charged. Brady Sharpshooter Alfred Apted wrote: “…in the short space of 5 minutes [they (the Rebels)] lost a great number of men and officers.”

Chamberlain would be wounded six times following Gettysburg, be awarded the Congressional Medal of Valor for his role there, serve four terms as governor of Maine, and be hired as President of Bowdoin College, where he had been a professor prior to volunteering for the War. One of the battle wounds Chamberlain received was so serious that his doctor did not expect him to live, and his obituary was printed in the newspaper the next day.

Earlier in the battle, the Brady Sharpshooters had nullified an entire company. Colonel William Oates of the 15th Alabama later wrote that Union troops (probably U.S. sharpshooters and Third Brigade Sharpshooters) had scared off an entire company of his which he had sent to capture Union wagons parked behind the Round Top as the battle was beginning. This company never resumed their attack. Rather, they loitered nearby and played the role of spectators during the rest of the battle.

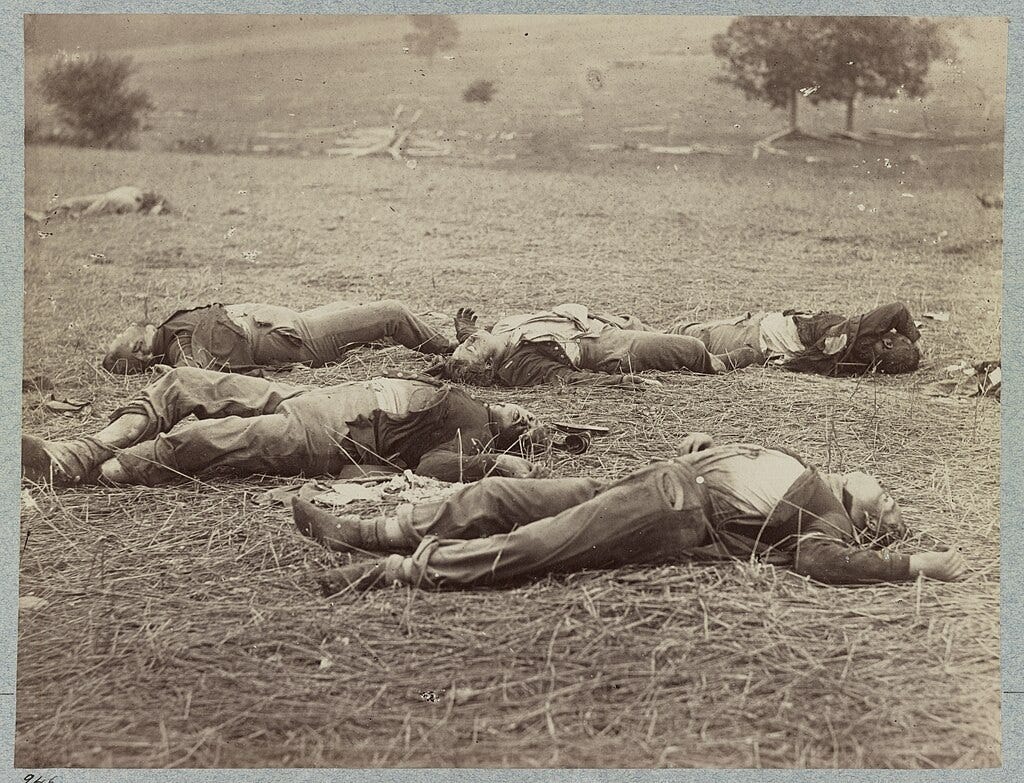

No more desperate fighting occurred during the Civil War than at Gettys burg, nor was greater tenacity and dogged persistence displayed on any field of battle than was seen that day by both sides. The three-day battle resulted in 51,000 casualties.

Relating the emotions felt there that day, Lieutenant Salter wrote:

We have been engaged in other battles where we have had more men cut down by artillery, but we never had such a terrible, close bayonet fight before. It seemed as if every man on both sides was actuated by the intensest hate, and determined to kill as many of the enemy as possible, and excited up in an enthusiasm far exceeding that on any battlefield before that we have been engaged in. I know I felt so myself although I never did before.

Corroborating the fierceness of the fighting, John Stevens of the 5th Texas said “The balls are whizzing so thick around us that it looks like a man could hold out a hat and catch it full.”

The booming artillery attacks of both sides were heard as far away Pitts burgh (a distance of 185 miles).

Years later, Colonel Edward Hill of the 16th Michigan said in an 1889 speech dedicating a monument to the 16th Michigan on Little Round Top:

Neither the pen of the writer, the pencil of the artist, the rhetoric of the orator, can describe the horrors of the scene. Nor can the enactments of legislatures add glory to the renown of those who died here that the Nation might live. Comrades of the gal lant Sixteenth, these memories are the ghastly legacies bequeathed the veteran, who in retrospective silence recalls the close of that dreadful day.

An important episode in the battle had been precipitated by a ruse on the part of the north. Following fierce mutual artillery shelling, the northern cannons were deliberately made silent by them, hoping to give the southerners to understand they had been taken out, luring them up the hill towards them. The stratagem succeeded. The charge of George Pickett and his men ended in disaster for the rebels, who were slaughtered en masse by the waiting Union artillerists. In “Battle Cry of Freedom,” McPherson writes that “Pickett’s charge represented the Confederate war effort in microcosm: matchless valor, apparent initial success, and ultimate disaster.”

The news of the Army of the Potomac prevailing over that of Virginia at Gettysburg reached Washington, D.C. on the 4th of July. The Philadelphia Enquirer ecstatic headline was “VICTORY! WATERLOO ECLIPSED!” Twenty-three thousand Union and twenty-eight thousand Confederate soldiers died there.

The day after the Battle of Gettysburg, July 4th, U.S. Grant’s army caused the fall of Vicksburg, Mississippi (Vicksburg citizens’ bitterness over this siege was so strong and sustained that Vicksburg did not again celebrate the fourth of July until World War II). Three days later, word of Vicksburg’s surrender also reached the nation’s capitol. A week later, drafting of Union soldiers began.

While the battle of Gettysburg itself lasted only three days, doctors would stay busy on the scene for months, ministering to the needs of the wounded. For every resident of Gettysburg, there were 10 battle casualties.

After sallying forth on the 5th to verify that the Confederate army had retreated, the Sixteenth crossed the mountains and pursued them across the Potomac River. They were constantly on the march, skirmishing and fighting and participating in various movements with the Army of the Potomac. During this year, the 16th marched over 800 miles in all.

At Kelly’s Ford on the Rappahanock River, the Sixteenth again demonstrated its gallantry under fire. After capturing the Confederate works, they remained at the Ford until November 26th.

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Questions: Have you read Shelby Foote‘s Stars in Their Courses: The Gettysburg Campaign? Have you read Stephen W. Sears’ Gettysburg? Have you read Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels? Have you seen the movie Gettysburg? Which former U.S. President took up residence in Gettysburg on his retirement, and why?