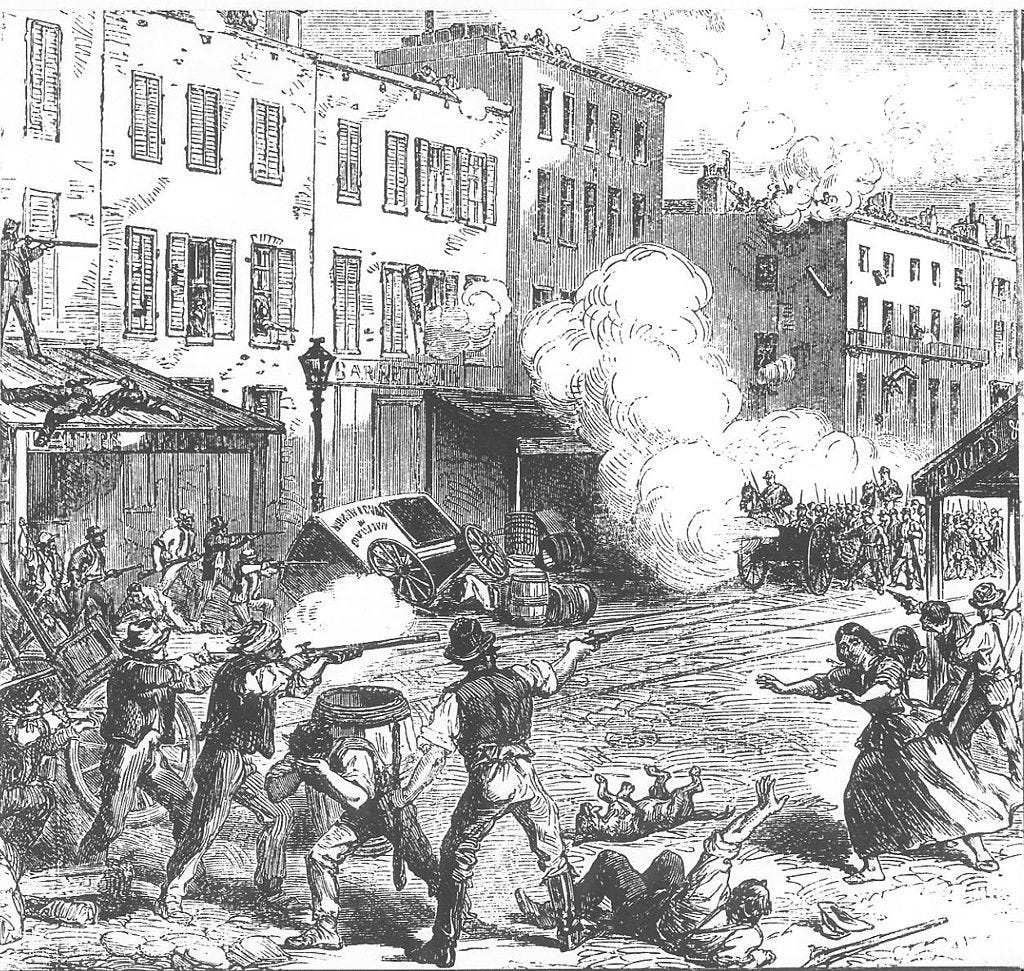

1863 — Draft Riots in NYC

public domain image from wikimedia commons

After the pressure to join the war effort became stronger, many in New York City rioted in rebellion against it. Part of their ire was because the emphasis of the war had shifted to being primarily about the abolition of slavery (which many white people weren’t especially fervent about, even in the North) and the fact that people of means or connection could weasel their way out of the war, by paying a $300 commutation fee (not really so unlike modern times, where the well-connected often found a way out, e.g., during the Vietnam War).

The riots began on this date in New York City in 1863, when a mob burned the draft office. The rioters did not limit their acts of violence to buildings, though: the homes of the wealthy were also targeted, as were newspaper offices, and even well-dressed men, policemen (although many of the rioters and many of the policemen were Irish), and African-Americans, with their places of employment burned down, also an orphanage (the children fortuitously escaped); the mayhem went so far that there were lynchings of blacks by the mobs, too.

The riots raged until Union forces were brought in, some soon from the battlefield at Gettysburg. More than 1,000 people during the riots, which also caused two million dollars in property damage (the equivalent of over $50 million in 2025).

The rioters were rewarded, though, in that the draft was suspended in NYC for a time, conscription standards revised, and — due to the continuing animosity of many New Yorkers toward the war — few residents of the city were ever called up.

The following is what I wrote about the New York City Draft Riots in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

Although response had been enthusiastic at the beginning of the war, as it dragged on longer than expected—as wars are wont to do—Lincoln had a challenge on his hands regarding replenishing his army with fresh troops. Especially was this a problem with an aggressive general such as U.S. Grant calling the shots. This was the case even though the man who came to be known as “Unconditional Surrender” Grant had the largest army in the world at his disposal—over 500,000 men.

Promising the blacks liberation meant that free blacks in the North who volunteered would be fighting for the liberation of their wives, mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, and friends in the South. The Union needed still more men, though. That is why Lincoln found it necessary to institute con scription of troops.

Not all civilians were fired up in opposition to the idea of enforced servi tude when such was being endured by other people. Especially was this the case when many of them thought that blacks thus liberated would migrate north and compete with them for scarce jobs. The temporary loss of their own freedom, though, and possibly their lives, for a cause they did not necessarily espouse, coagulated enough bad blood that there were draft riots in New York City—which city had itself earlier considered seceding from the Union.

Two things in particular irked those who were likely to be drafted: The fact that those who could afford to could buy their way out of the draft by purchasing an exemption, and the fact that blacks were not among those drafted. The burden of enforced service fell on the poor whites. The mid-summer heat in those pre-air conditioner days didn’t help matters, either. Eventually 50,000 protesters began looting and burning, attacking and lynching those they held responsible for their unenviable situation.

Martial law was imposed, and hundreds of rioters were shot. Beginning July 13th, the riots continued until the 16th. New York police fought the mobs on the 13th and 14th. Union troops arrived from Gettysburg on the 15th to assist the police in quelling the disturbance, which finally ended on the 17th, when an uneasy peace set in. According to one source, by the time the riots were over, twelve hundred people had died. In “Battle Cry of Freedom,” on the other hand, McPherson says “at least 105” (implying there were likely more victims than 105, but presumably not over ten-fold more).

James Shannon may have been there, among the soldiers quelling the disturbance. If he was, he presumably would not have felt overly sympathetic towards the rioters, as he, a Canadian, had not only volunteered two years prior in 1861, but was to also re-enlist later in the year. There were also draft riots “back home”—or at least in the vicinity of home, at the place he had volunteered—namely, in Detroit, Michigan.

Wiley’s “The Life of Billy Yank” quotes a soldier from New York recom mending the following treatment for those who had fomented the riots:

Hang the leaders…hang them, damn them, hang them…I would show them no mercy…What a pity there was not force enough to cut them down in heaps. How I would like to stand by a gun and mow them down.

A situation that really irked the Union soldiers was that those drafted who could afford to do so could pay $300 to avoid conscription, or pay a substitute to take their place. Among those who paid substitutes to fight in their stead were future Presidents Chester Arthur (1881–1885) and Grover Cleveland (1885–1889, 1893–1897), as well as prominent businessmen such as J.P. Mor gan, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Jay Gould, and James Mellon. Mellon may have felt pangs of guilt over buying his way out, for his father wrote him consolingly: “A man may be a patriot without risking his own life or sacrificing his health.” But such risks are what the wealthy class asked those “less fortunate” to take. How did they reconcile this discrepancy? Mellon’s father went on to assert: “There are plenty of lives less valuable.”

In his For Cause and Comrades, James McPherson wrote of the response in the field to this situation:

One of the things that most embittered Union soldiers in the last two years of the war was the opportunity for drafted men to hire a substitute or pay a commutation fee of $300. “The columns of the daily papers [from the North] I see filled with advertisements of Northern cowards, offering large sums for substitutes to take their places in the ranks,” wrote an Illinois captain with Sherman’s army before Atlanta in August 1864. “Oh! How such men are despised here!…We who are already in the field must do our whole duty now, for it is daily becoming painfully evident those at home do not intend to do theirs.”

By August 19th, troop strength in Manhattan had been increased to 20,000, and the draft was resumed. The government could not let the rioters “win” for that could encourage similar uprisings elsewhere. However, the city thereafter came up with money on its own to pay the commutation fees for all the men in the city who were subsequently drafted.

There were also draft riots (and bread riots) in Southern cities this summer.

As to the likelihood of northern men actually going to war for those con sidered eligible (able-bodied men between the ages of twenty and forty-five), the chances were very high they would never fire a gun in anger: of the 776,000 who were listed as eligible, only 207,000 were drafted.

One fifth of the larger number didn’t even show up, fleeing into the woods, north to Canada, or to the west; one-eighth were sent home due to already f illed quotas for their area (each area was required to supply a specified number of soldiers based on the area’s overall population); and two-fifths were exempted for various reasons. This left the figure of 207,000 given earlier.

Of the remaining 207,000, only 46,000 personally served. 87,000 paid the $300 commutation fee (indirectly furnishing substitutes, as this money could then be paid out as enlistment bonuses); 74,000 furnished substitutes directly (eighteen and nineteen-year-olds, as well as immigrants who had not filed for citizenship and were thus not liable for the draft).

As a result, of the 776,000 tabbed for potential service, only one in seven teen actually did serve; and of the 207,000 who were obligated to either serve personally, pay the commutation fee, or provide a substitute, only two in nine ended up in the army themselves.

By far the lion’s share of those who served were volunteers. Just during the draft period (thus disregarding those who had volunteered earlier, such as James Shannon), the army’s new members was comprised of 46,000 draftees, 74,000 substitutes, and 800,000 volunteers.

As to those who did not care to volunteer, nor serve if conscripted, draft insurance policies were available. For a few dollars per month, a premium of $300 was paid to policyholders in the case that they were drafted.

Questions: How did the war protests of the Vietnam (War) era differ from these riots? How many of the Irish rioters attacked friends or even family members who served on the police force?

1930 — First World Cup Football (Soccer) Match

public domain image from wikimedia commons

On this date in 1930 in Montevideo, Uruguay, the first day of the first World Cup of soccer was played. On that day, France and the United States won their matches.

In the intervening century (almost), that type of football (what we United Statesians call Soccer) has become the most popular sport in the world.

Host Uruguay won the title, defeating Argentina 4-2 in a rematch (and re-run, of sorts) of Uruguay’s victory over Argentina in the 1928 Olympics (the Olympics had eliminated soccer/football from their games, which was the impetus for the World Cup).

The United States fared better in that first World Cup than they ever have since, enduring to be one of the final teams still in contention until the (bitter) end.

Questions: Why did many European soccer clubs fail to show up for the World Cup? Have you ever played soccer? Do you like to watch soccer? Why is soccer not often shown on U.S. television, despite its massive popularity? Why is American football even called “football”?

1985 — Live Aid Raises Beaucoup Bucks and Hackles

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Forty years ago today, the international concert to assuage the suffering of famished people in Africa (specifically Ethiopia and Sudan), was staged by Bob Geldof (born 1951) of the Irish band The Boomtown Rats. The concerts took place in two places: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and and London, England.

The concerts were seen in-person and remotely by more than a billion viewers (one of out five people on earth at the time [nobody counted how many dogs, cats, and other critters also saw/heard the concerts]) from 110 Countries (two-thirds of them).

More than $10 million was raised for famine relief, and thus the concerts were a great success, saving countless lives while also entertaining many. Inspired or prodded (or even shamed) to do what they should have done earlier, affluent Nations were then moved to provide surplus grain to the starving masses in Africa.

Some of the artists who donated their time and talent to the effort were Bryan Adams, the Beach Boys, Eric Clapton, Phil Collins, Elton John, Tom Petty, Queen, Santana, U2, the Who, and Neil Young.

At the end of the concert in London, Paul McCartney and Who guitarist Pete Townshend lifted up concert organizer Bob Geldof as a tribute to his contributions to the event. Geldof was later knighted.

Questions: Why is their “surplus grain” while people starve? What is more important: money or human life? What reprise did Geldof and his “co-conspirators” put on twenty years later, in 2005?