The Mysteries of History (March 18 Edition)

Tri-State Tornado; Texas School Explosion; American Concentration Camps

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” — Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana, 1905

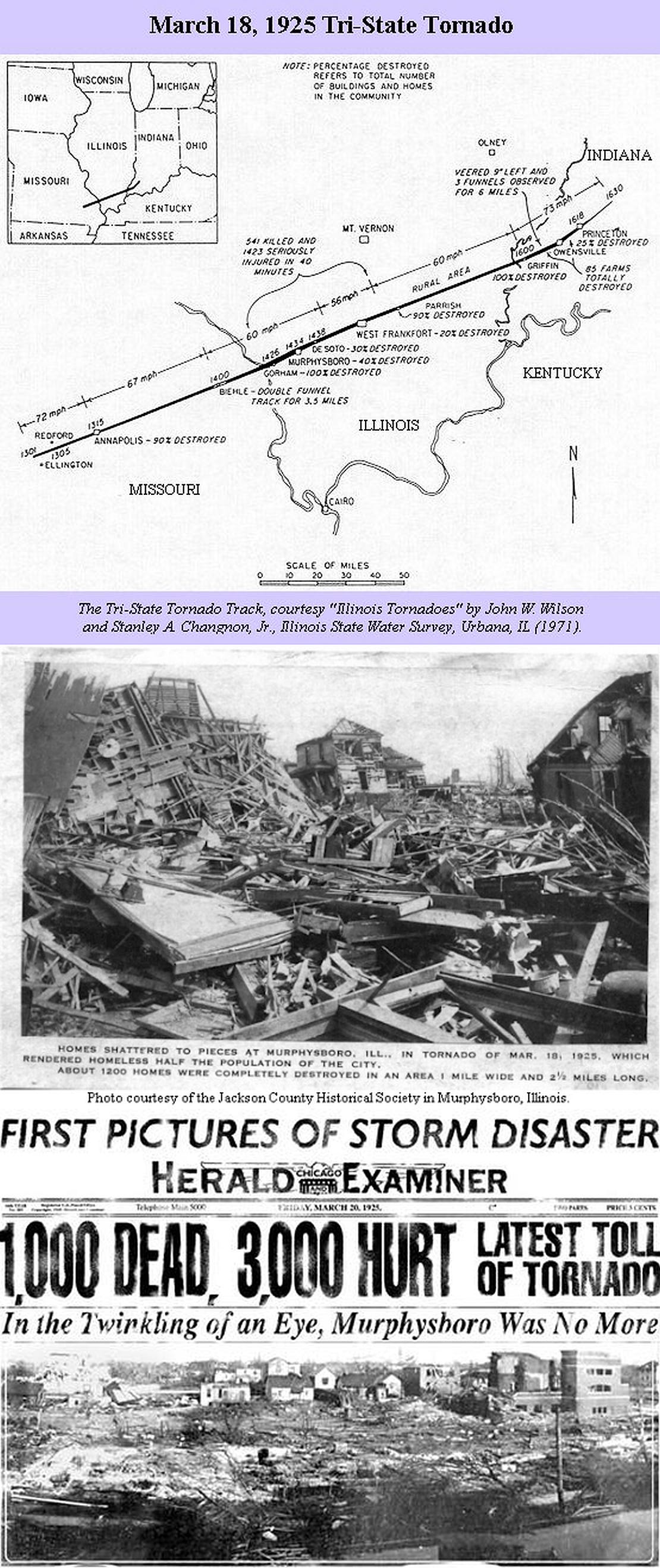

1925 — “Tri-State” Tornado Hits Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana

public domain images from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the Tri-State Tornado in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

In the Kollenborns’ previous home states of Missouri (where some of them still lived) and Illinois (as well as Indiana), a massive tornado resulted in the deaths of 689 people this year. An additional 2,000 were injured. It remains the most destructive tornado in U.S. history.

(The Kollenborns, originally from Romanshorn, Switzerland, are my relatives on my mother’s side).

According to other sources, another six people died (695) and an additional 11,000 were injured. Southern Illinois was hardest hit, with 500 killed there, 234 in Murphysboro alone (shown in the images above), which essentially destroyed that city.

Questions: What accounts for the drop in population of Murphysboro by 10,000 between 1920 and 1930 when “only” 234 perished as a result of the tornado? Why does the newspaper report overstate the number of dead, but understates the number of wounded? Has Murphysboro been visited by any other tornados since the Tri-State Tornado?

1937 — Natural Gas Explosion at a Texas School Kills Hundreds

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The placard pretty much tells the story. On this date in 1937, almost 300 people died in an explosion at a school oddly situated in the middle of an oil and natural gas field. In an effort to save money, school officials had decided to use a less expensive but more dangerous form of gas (“wet gas”) to power the school.

In the late afternoon, as the bell signaling the end of the day was within ten minutes of ringing, the blast blew the roof off the school and leveled it. Of the 734 in the school at the time, almost half of them were killed, mercifully instantly in most cases.

Found in the rubble was a sign that read, “Oil and natural gas are East Texas’ greatest natural gifts. Without them, this school would not be here and none of us would be learning our lessons.” With them, though, the school was no longer there, and hundreds never learned any more lessons.

There was one important lesson learned and applied, though: Nobody detected the natural gas leak because it was odorless. Henceforth, a bad odor was added to natural gas so that people could tell when there was a leak. Texas was first to enact this law, other States soon followed, and eventually it became federally mandated throughout the Country.

Questions: How much money did the school save by using the cheaper form of the gas? Have you heard of the saying, “Penny wise and pound foolish”? Where did the surviving students end up going to school? Besides the 694 students and 40 teachers, were there others in the school at the time (office staff, janitors, visitors, etc.)?

1942 — “War Relocation Authority” Rounds Up Suspect Americans

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the internment of Japanese Americans in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

“They that can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.”—Benjamin Franklin

Many people in California, from the Turn of the Century up to the 1930s, considered an invasion by Japan to be inevitable. The friction between Japa nese-Americans and Euro-Americans was not so dissimilar to that between Germans and Jews in Germany during this time period. Many Germans viewed Jews with distrust and jealous animosity due to the perception that the Jewish men were “stealing” all of the most beautiful German girls (Jews in Germany at the time apparently tended to be more affluent than the Aryans and thus—as is often the case in sexual economics—“got the girls”). In California, it was not necessarily so much a case of Japanese men con sorting with Euro-American females, but rather that they were excelling in business, particularly in agriculture. By 1920, there were more Euro-Ameri cans working for Japanese employers in California than vice versa. Although many of them had been in America just as long or longer than their Euro American counterparts—many of whom were of German or Italian descent—110,000 of them ended up being incarcerated, or “interned,” during World War II. Tens of thousands of Japanese families were turned out of their homes and businesses and forced to spend the duration of the war in concentration camps throughout the country. It was, ostensibly at any rate, fear that these Japanese Americans would collaborate with the Japanese military that prompted these violations of their rights. Similar to the “one drop” rule which relegated any one with any African-American ancestry to a life of slavery in the old South, anyone with as little as one-sixteenth Japanese blood was a candidate to be incarcerated in these camps. Native Americans were also taken advantage of during the war as a result of government action. One and a half million acres of their land in Arizona, South Dakota, and Alaska was taken from them for use in the war effort. Among the ways their land was used was: As gunnery ranges, for nuclear test sites, and…internment camps for these very Japanese-Americans. As of October 12th of this year, though, Italian nationals would no longer be considered enemy aliens. A year and a day later, Italy would reverse its alli ances and proclaim war on Germany, its former Axis power partner. One of the Japanese internment camps was located in Minidoka County (where the Albert Kollenborn family was living) north of Twin Falls and near the town of Hunt. Minidoka County has been described as having hot and dusty summers and frigid winters. Oddly enough, Japanese-Americans already living in Idaho were not relocated to any of these camps. For that reason, some Japanese-Americans from other areas voluntarily relocated to the state. Doing so saved them from removal to the camps—but not necessarily from prejudice and distrust on the part of some of their fellow citizens. In fact, patriotic fervor and fear of the enemy were at a fever pitch. Such fear was not utterly groundless. The Japanese did not intend their attack on Pearl Harbor to be a singular event, but just the first salvo in a series of attacks on the United States. After conducting a screening operation off the island of Oahu, Japanese sub commander KozoNishino’s next assignment was to move with eight other submarines of his squadron to the Pacific Coast of the U.S. They were to dis rupt shipping and communication. From off the coast of Washington state, Nishino went south to Cape Mendocino (near where Pop Shannon and his family were living), then proceeded further south to San Francisco. Operating off San Francisco, Nishino sank an American freighter in mid-January. An even more shocking attack followed. In February of 1942, Commander Nishino received orders to head for the coast of Southern California. From San Diego, he turned north towards Santa Barbara, running submerged by daylight, and cruising on the surface past the lights of the California coast in the evening. On February 23rd, shortly after seven p.m., Nishino stood in the conning tower of his submarine and raised his binoculars to his eyes. Commander Nishino could have torpedoed this American city at the very moment that FDR was conducting a radio address to the nation. Occurring just two and one half months after the strike on Pearl Harbor, such an attack on a mainland American city would have instantly earned its place (in infamy) in American history. This would have been the first time since the War of 1812 that a foreign power had directly attacked an American mainland city. The affect it would have had on Americans is easily predictable: Increased anger towards and fear of their adversary. The prognostications for a full-scale Japanese attack up and down the coast would have been elevated from a possi bility to a probability or even a virtual surety. In fact, the military was already claiming that the Japanese had been oper ating in California airspace. The book Embattled Dreams—California in War and Peace by Kevin Starr relates:

The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Brigadier General William Ord Ryan, commanding officer of the 4th Interceptor Command, had confirmed that a large number of unidentified aircraft had approached the Golden Gate in the late hours of 7–8 December but vanished after searchlights from the Presidio of San Francisco f looded the sky. ‘They came from the sea,’ Ryan was reported to have said, ‘[and] were turned back, and the Navy has sent out three vessels to find where they came from. I don’t know how many planes there were, but there were a large number.

They got up to the Golden Gate and then turned about and headed northwest.’ General Ryan personally confirmed the sighting to Mayor Angelo Rossi of San Francisco.

In 1989, the Internment Compensation Act was passed. Every surviving Japanese-American internment camp victim received a belated twenty thou sand dollars. Some had lost millions of dollars in property during the two and a-half years of internment.

Ten weeks after Pearl Harbor was bombed, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered that Japanese, German, and Italian nationals, as well as Japanese Americans, be barred from areas deemed militarily sensitive. While around 2,000 Germans and Italians were interned (including Germans in Milwaukee, a city with many of German descent), sixty times that number (120,000) Japanese were rounded up and interned.

In the concentration camps (“Relocation Centers”), those housed in the quasi-prison like accommodations were not allowed to use razors, scissors, or radios.

The next year (1943), Japanese who had not been interned were allowed to join the U.S. military. More than 17,000 did, but many of them sent their letters “home” to these “Relocation Centers.”

In 1990, the U.S. government formally apologized to those interned (but by that time FDR had been dead for 45 years, as no doubt everyone else was who had helped make the decision to intern; thus, those who apologized didn’t have as much “skin in the game” or emotional investment in it, and were not responsible for the internments in the first place). In addition to the belated “whoops,” the government also provided internees still living as well as their heirs with checks in the amount of $20,000.

Questions: Do you think the internment of Japanese Americans was justified? What about the German and Italian nationals? If a similar thing took place today (America was attacked by a foreign country, a la “Pearl Harbor”), do you think the government’s reaction would be different than it was in 1942? For example, if China attacked the U.S., would all Chinese Americans be rounded up? What if it were Russia who attacked? Iran? Grand Fenwick?

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.