The Mysteries of History (March 20 [Spring Equinox] Edition)

Uncle Tom's Cabin; LBJ Sends Troops to Alabama; Tokyo Subway Sarin Gas Attack

1852 — “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” Published

public domain images from wikimedia commons

In “Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History, 1620-1913” (Volume 1), I wrote the following about H.B. Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”:

The Civil War, almost ten years in the future, did not arise overnight or come as a complete surprise. Animosity between the agricultural south and the industrial north had been building for decades. Slavery was one of, but certainly not the only, point of contention between the two disparate regions. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin engendered strong anti-slavery feelings among people formerly ignorant, undecided, or apathetic about the issue, and hardened the resolve of those who were already abolitionists. Stowe accomplished this by putting names and faces—albeit fictional—to the unwilling inmates of the “peculiar institution” of slavery. It has been said that “The pen is mightier than the sword.” Whether or not that is true, in this case the pen seems to have led to the sword. Abraham Lincoln is thought to have once referred to Mrs. Stowe as “the little lady who wrote the book that made this big war.” As for Stowe herself, she always insisted that it was not she that wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but God. The “little lady’s” novel retained its popularity long after the Civil War ended. Even decades later, troupes of traveling actors recreated the story on stage throughout the country, even in small towns.

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) was the daughter of famous Presbyterian minister Lyman Beecher, who had 13 children, among them (besides Harriet) were preacher/orator Henry Ward Beecher, suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker, and Thomas K. Beecher, who was a good friend of and minister to Mark Twain and his family in Elmira, New York. Harriet was also a neighbor of the Twain (Clemens) family in Hartford, Connecticut at the end of her life (as was her sister Isabella Beecher Hooker).

When Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Beecher Stowe danced in the streets of Cincinnati, the city where she had come into contact with escaping slaves and abolitionists (Cincinnati is located on the banks of the Ohio River, which separated free State Ohio from slave State Kentucky, and features in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”).

Whereas her father had a baker’s dozen of children, Harriet had “only” seven.

Questions: How did the success of her novel affect Beecher Stowe’s life? Did she write other popular books? What was her relationship with her neighbors in Hartford, the Mark Twain/Samuel Clemens family? What does it mean to call someone an “Uncle Tom”?

1965 — LBJ Sends Federal Troops to the South

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Three score years ago today, President Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ, 1908-1973) stepped in to support those struggling to secure civil rights for themselves and others by sending troops to keep order.

The following is what I wrote about the Civil Rights events of 1965 in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

On March 21st, a group of four thousand began a Civil Rights march that began in Selma, Alabama, and ended in that state’s capital of Montgomery. It was not a “walk in the park” for the marchers. One portion of the march, along the Jefferson Davis highway, was described this way in the book “Eyes on the Prize” by Juan Williams:

As the marchers approached the far side of the [Edmund Pettus] bridge, Major John Cloud ordered them to turn back. “It would be detrimental to your safety to continue this march,” he said. “You are ordered to disperse, go home or to your church. This march will not continue. You have two minutes…”

[Hosea] Williams asked, “May we have a word with you, Major?” Cloud replied that there was nothing to talk about. He waited, then commanded, “Troopers advance.” Fifty policemen moved forward, knocking the first ten to twenty demon strators off their feet. People screamed and struggled to break free as their packs and bags were scattered across the pavement. Tear gas was fired, and then lawmen on horseback charged into the stumbling protesters.

“The horses…were more humane than the troopers; they stepped over fallen victims,” recalls Amelia Boynton. “As I stepped aside from a trooper’s club, I felt a blow on my arm…Another blow by a trooper, as I was gasping for breath, knocked me to the ground and there I lay, unconscious…”

These depredations were all over the news, and decent Americans were outraged. Segregationists actually hurt their cause and hastened on legal redress. President Lyndon Johnson, in a televised speech, said of the Civil Rights proponents: “Their cause must be our cause, too. Because it’s not just Negroes, but it’s really all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.”

* * *

OnAugust 6th, the Voting Rights Act was passed. Among its provisions, as enumerated by John Lewis in his book “Walking With the Wind” were:

• The suspension of literacy tests in twenty-six states, including Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi

• The appointment of federal examiners to replace local officials as voter registrars

• Authorization for the Attorney General to take action against state and local authorities that use the poll tax as a prerequisite to voting As we will see in the 2000 chapter, though, the suppression of black votes was not completely done away with via this legislation.

John Lewis certainly highly touts the Voting Rights Act. He goes on to write about the day the Act was passed:

That day was a culmination, a climax, the end of a very long road. In a sense it rep resented a high point in modern American, probably the nation’s finest hour in terms of civil rights. One writer called it the “nova of the civil rights movement, a brilliant climax which brought to a close the nonviolent struggle that had reshaped the South.”

Yet, righteousness cannot be legislated. Hatred, prejudice, and violence cannot be gaveled out of cold, unreasoning hearts. Less than a week later, the Watts Riots would begin. Lewis gives the reason for this spilling over of frus tration and anger:

We now had the right to vote. We now had the right to eat at lunch counters. We could order that hamburger now…if we had the dollar to pay for it. Far, far too many of us, unfortunately, did not have that dollar. That was the challenge ahead of us now. Now that we had secured our bedrock, fundamental rights—the rights of access and accommodation and the right to vote—the movement was moving into a new phase, a far stickier and more complex stage of gaining equal footing in this society. The problem we faced now was not something so visible or easily identifiable as a Bull Connor blocking our way. Now we needed to deal with the subtler and much more complex issues of attaining economic and political power, of dealing with attitudes and actions held deep inside people and institutions that, now that they were forced to allow us through the door, could still keep the rewards inside those doors out of reach. Combating segregation is one thing. Dealing with racism is another.

1965 is considered to be the end of the modern Civil Rights era. What began with a Supreme Court victory in 1954 (Brown v. Board of Education) culminated with the Voting Rights Act just delineated.

It doubtless irked Alabama’s racist Governor, George Wallace (1919-1998), that LBJ used his own authority to call up the Alabama National Guard to keep the Civil Rights marches civil, but he did that because Wallace reneged on calling them up under his own authority, demanding that LBJ instead send in federal troops.

Questions: Who attempted to murder Wallace, when, and why? Why was a Voting Rights Act needed? Are there currently any George Wallace-like (racist) characters in national politics?

1995 — Tokyo Subway Attack

image generated using Bing Image Creator

public domain image from wikimedia commons

On this date exactly thirty years ago, Nazi-invented Sarin nerve gas was released in the Tokyo, Japan subway system, killing 12 people and injuring more than 5,000.

The gas was planted by a doomsday cult. They apparently wanted to force their prophecies to come true. Their leader claimed to be able to time travel and that he was Jesus. If he could travel into the future, why didn’t he scope out the end result of his group’s demented deeds?

While searching for this weirdo, the authorities found one of the group’s camps had tons of the chemicals needed to produce Sarin; they also found plans to purchase nuclear weapons from the Russians. Some of the leaders were found, including one who was killed by an angry citizen while being taken into custody and the chemist who made the gas. Meanwhile, the group carried out more attacks on subways and even killed the nation’s top policeman.

Finally, the chief goofball was discovered in a hidden room in the compound near the base of Mount Fuji where the chemicals and nuclear plans were found.

Seven cult members, including the leader, were hanged in 2018.

Questions: How is it that people get tricked into believing in people so wacky and evil? Why did it take so long (23 years) for those responsible for the mass murders / acts of terrorism to be executed?

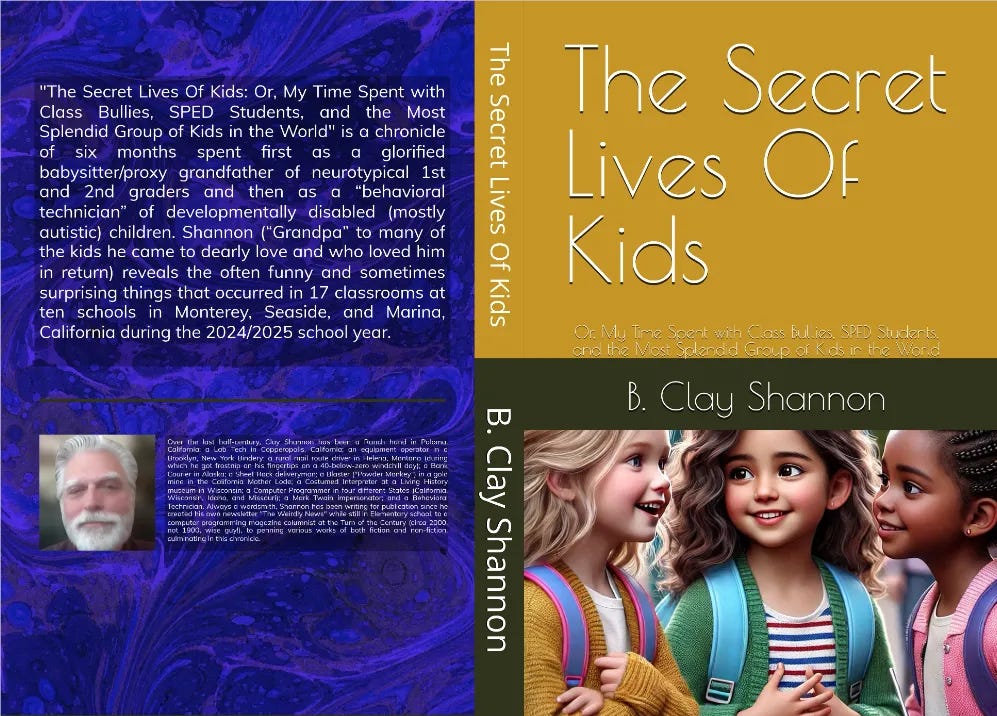

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.