The Mysteries of History (March 22 Edition)

First Native American/Colonist Peace Treaty; Stamp Act; Equal Rights Amendment

1621 — First Native American / Colonist Peace Treaty

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the Wampanoag Peace Treaty in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

“Native Americans do not celebrate the arrival of the pilgrims and other European settlers…To them, thanksgiving day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of their people, the theft of their lands, and the relentless assault on their culture.”—Inscription on statue of Wampanoag Chief Massasoit in New England

“We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock—Plymouth Rock landed on us!”—Malcolm X

“Many Indians, of course, believe it would have been better if Plymouth Rock had landed on the Pilgrims than the Pilgrims on Plymouth Rock”—Vine Deloria, Jr., from “Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto”

“Howdy, Pilgrim!”—John Wayne

Squanto, who died the next year (1622), was useful not only in aiding the Pilgrims’ trade, but also in dealing with the local Indian tribes. Understanding both Wampanoag and English, he served as interpreter and peace-broker between that local tribe and the Pilgrims particularly in March of this year. The Wampanoags had a nearby enemy in the Narragansetts, and they felt having the English and their impressive guns on their side was to their distinct advantage. The crux of the treaty was:

1. The Pilgrims and Wampanoags would not harm one another, neither by physical violence nor by theft.

2. If an Indian injured a Pilgrim, he would be delivered over for punishment.

3. The Pilgrims and Wampanoags would defend one another against enemies.

4. When the The Pilgrims and Wampanoags visited one another, they would leave their weapons outside the camp being visited.

The time would come when the Wampanoags and Narragansetts, instead of fighting one another, would join forces against the English. In fact, John Howland’s future son-in-law John Gorham would die fighting the Narragansetts a half century after this treaty. Perhaps just as importantly as being the peace broker, Squanto served as agricultural adviser and consultant to the Pilgrims. He showed them that they needed to add fish to their corn hills in order to get a good crop. Yes, there would have been no harvest of corn for the Pilgrims had the Indians not pro vided seed (without being asked—the Pilgrims had initially raided some of the Wampanoag corn caches in order to have seed to plant) and agricultural expertise. This situation was similar to that down south in Jamestown, Virginia, where the Powhatan’s helped the English settlers make it through the harsh winter of 1607–1608.

Squanto was, perhaps, not totally altruistic in his role as peace broker. Massasoit would later request of the Pilgrims that they chop off Squanto’s head and hands, and send these body parts to him via his emissaries. Apparently, Squanto had taken advantage of his bilingualism to play the colonists against the Wampanoags to his own material advantage. At any rate, that is what Massasoit thought.

Questions: If native Americans of modern times could travel back in time to the 1600s, what would they tell the Indians of that time? If native Americans from the 1600s could have traveled forward in time to our days, what would they tell the Indians of our time? Similarly, what would the European Americans tell their counterparts in other time periods, if that were possible?

1765 — Imposition and Abolishment of the Stamp Act and Its Ramifications

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the Stamp Act in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

As touched on in the previous chapter, the British government needed money to pay for the war it had waged from 1756 to 1763. As much of the costs had been incurred in defending its American colonies, many in England believed it only fair and reasonable that the Americans pay for such protection and assistance. The British government also required an enormous sum, on an ongoing basis, to sustain their overseas military establishment.

Citizens in Britain were already the most heavily-taxed people in western Europe. Predictably, the idea of increasing taxes to those in Britain in order to pay for these expenditures was met with an outcry there. Let the Americans pay for the services rendered them by the Crown! The Americans, as a whole, felt differently about the matter, though. Now that the French were no longer a threat to them, of what further use to them were the redcoats? Formerly they had proved beneficial as a check against the French and the Indians, but now the Americans felt they could get along without the British soldiers. This disconnect between how the British viewed their importance to Americans, and how the Americans viewed the necessity of a continued British presence, was to prove pivotal in events to come.

To raise the money they needed without taxing their “home” citizens more heavily, the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act this year. It required that all legal and commercial documents, newspapers and even playing cards be imprinted with an “official seal.” This seal had to be purchased by the manufacturer of the goods in question. This requirement provoked the wrath of the colonists living in America, who had heretofore not been taxed in such a way, having been allowed to govern themselves on such matters. Riots and mob violence broke out in Boston and New York.

Only the wealthier class were taxpayers, but the remainder of the populace were upset about another matter: impressment (involuntary conscription) into the Royal Navy. This very Navy, in which they were forced to serve, could be used as an instrument to enforce the restriction of free trade in America, their home. So both the wealthy and the poor in America were united in their belligerence toward the crown—a rare situation, and an ominous and precarious one for the British government.

Also of deep concern to the Americans regarding the Stamp Act was that they did not want a precedent set—if they acquiesced in this area, what might be next? The Americans felt as if they were being treated like children, or slaves—being told what to do without being first consulted. By imposing such requirements on legal documents and playing cards, the English managed to irritate two elements of society which could prove to be the most problematic: on the one hand, lawyers, the most argumentative and articulate segment of the population; and on the other hand, sailors and other gambling rowdies, a most irreverent and incendiary class of men.

The Stamp Act was so fervently opposed by the colonists that it was quickly (in March of 1766) repealed. However, Britain soon came up with another way to squeeze money out of the colonists—by placing duties on imports. This further raised tensions between the “mother country” and her “children,” leading to more violent conflicts over the next several years.

Britain also enacted the Quartering Act on March 24th of this year, which required American colonists to provide temporary housing to British soldiers.

The British government didn’t so much as “give in” to the American colonists over the Stamp Act as realize that it cost them more to uphold it than it would to abolish it — it was mainly a financial decision to appease the Colonists. The provocation of the Americans had longer-lasting repercussions, though, as groups who were offended by the heavy-handedness of the British government stayed in contact, eventually culminating in ever greater feelings of aggrievement, which led to the nationalistic fervor that brought about the Revolutionary War.

Questions: Had things turned out differently if Britain had never imposed the Stamp Act in the first place? Who were the primary rabble-rousers among the American populace (Patriots)? Who were the primary defenders of Britain among the American populace (Royalists)?

1972 — Equal Rights Amendment Passed by Congress But Not Ratified

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Almost 50 years after it was first proposed (49 years, to be precise), the Senate passed the Equal Rights Amendment, sending it on to the States for ratification.

The equality under discussion was related to sex, as women did not have the same legal and social standing as men and, of course, wanted it. Although quickly accepted by many States, a backlash against it ultimately led to the Amendment being shelved.

Although the federal government and individual States have passed laws protecting women, gender equality is still not guaranteed under all circumstances by the U.S. Constitution, as the required three-quarters of the States (37.5, rounded up to 38) did not ratify it by the deadline in 1982.

Questions: Are you surprised that the Equal Rights Amendment did not pass? Who were the leading figures pushing it forward in the 1970s? Which States refused to ratify it, and why didn’t they? In your opinion, which prejudice is the most deeply entrenched: racial, gender, or something else?

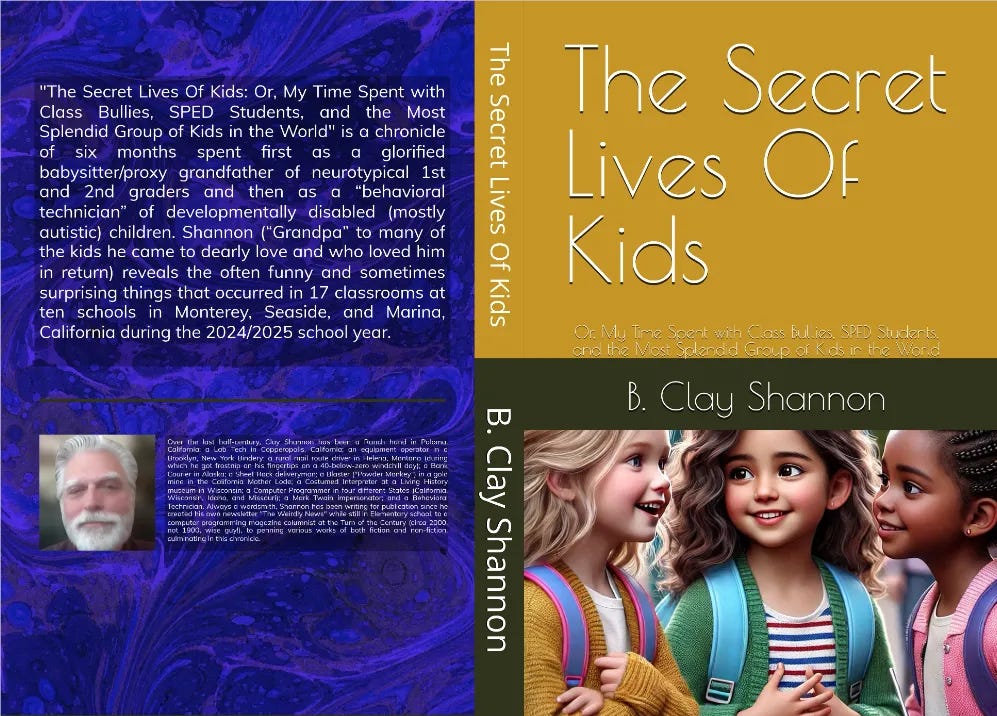

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.