“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” — Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana, 1905

1634 — Maryland Settled

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The region that now encompasses the State of Maryland, which is part of what is called the Mid-Atlantic region (of the United States), was settled on this date in 1634. Unless you are an avid genealogist, you probably don’t know the names of your ancestors who were alive back then, or where they were living at that time almost four centuries ago.

The first European-American settlement in what has been known as Maryland since 1788 was called St. Mary’s. You would be excused for thinking the State was named after the mother of Jesus (Mary Land or Mary’s Land), but it was actually named for Henrietta Maria, who was married to King Charles the 1st of England.

However, it is true that Maryland was set up with the intent of making it a place of refuge, or safe haven, for Catholics who were being persecuted in predominantly Protestant England.

There was strife in America, too, though, as the “Puritans” felt animosity toward the Catholics and tried to curtail their religion. In 1649, the Governor passed a law making it legally binding that all who believe in Jesus Christ enjoy freedom of religion (in other words, “Leave the Catholics alone, you so-called Puritans.”). This only lasted for so long, though, because the majority Puritans gained control of the area and repealed the Governor’s “Toleration Act.” Civil War ensued, and the controlling religion of the region toggled back and forth.

Persecution of Catholics continued until the 19th century, when many Catholics who immigrated to Maryland made Baltimore their home.

Questions: What percentage of Marylanders are currently practicing Catholics? What percentage of Marylanders are currently active members of other religious organizations? Why do people feel the need to fight one another because over differing religious or political viewpoints?

1911 — Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

On March 26th in New York City, unsafe working conditions led to what would rank as America’s worst workplace disaster until September 11th, 2001. Shirtwaists (blouses) had been popularized by Charles Dana Gibson’s “Gibson girl,” and were replacing corsets as de rigueur for the new, modern, twentieth century woman. Demand was great; shirtwaist makers were so busy that the workers often put in eighty-four hour weeks, and sometimes as much as one hundred or more.

Tragedies caused by bullets discharged from “empty” guns are perhaps only eclipsed in number by fires started by “extinguished” cigarettes. The latter phenomenon was the cause of a wicked inferno at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company in New York City. A supposedly extinguished cigarette had been discarded into a scrap bin at the factory. The resulting blaze ultimately resulted in the deaths of one hundred forty-six workers who had no other recourse when the flames reached them than to jump out windows on the eighth and ninth floors. The tallest ladder the New York Fire Department had did not reach high enough to rescue the trapped workers. The building’s fire escape was so inadequate that it could not bear the weight of those who attempted to use it. It collapsed in a Mobius strip-like heap of twisted metal, spilling its human contents out into the alley below.

More than eighty of the victims died from making impact with the ground, having either fallen, jumped, or been pushed by panicking co-workers behind them. Some of the women and girls (most of the workers were sixteen- to twenty-three year old immigrants of the feminine gender) were seen jumping out together, hand-in-hand, falling to their deaths. Crowds gathered on the street and watched in horror, unable to do anything to help the victims. Some of those falling and jumping from the buildings trailed flames from their clothing and hair. One girl seemed to be saved when her dress caught on a wire, suspending her in midair above the pavement. Shortly, though, the flames burned her dress—her lifeline—and she plunged the rest of the way to the street, to her death.

A thirteen-year-old girl clung tenaciously to life, gripping the windowsill on the tenth floor until flames reached her; she also fell to her death. Exacerbating the danger of the situation was the fact that the owners were so worried about theft by their low-paid employees that they kept one of the exit doors locked at closing time (the conflagration began right at the end of the work day). Because of this situation, all of the workers had to file past an inspector who would look into their purses, and frisk them if he deemed such necessary, to see that no shirtwaists were stolen.

After the conflagration ended, the crumpled bodies were picked up from the street and gathered from where they were strewn throughout the building. Many of the victims had fallen or jumped down the elevator shaft, and were found on top of the elevator car. The bodies were taken to a central location to be identified by family members. Many of the victims were so badly charred that this was a very difficult undertaking indeed. In most cases the victims were identified by a particular item of jewelry or something unique about their clothing.

The book “Triangle: The Fire that Changed America” by David von Drehle, reports:

Now and then a shock of recognition announced itself in a piercing cry or sudden sob splitting the ghastly quiet. When Clara Nussbaum found her daughter Sadie, she ran to the edge of the pier and tried to throw herself into the river.

Naturally, many heartrending stories could be told regarding individual victims and their families. One more of these, from the above-mentioned book, will suffice:

A teenager named Rosie Shannon* joined the line at 8 A.M. on the morning after the fire. After waiting several hours, she reached the rows of coffins and began filing past the burned and battered faces in search of her boyfriend, Joseph Wilson. He had come to New York from Philadelphia not long before, intending to marry her. The previous evening, Shannon waited for Wilson to meet her after work. They were planning to pick a date for their wedding, but he never arrived. She found his badly burned body in coffin No. 34. Though his face was beyond recognition, he was wearing the ring she had given him. Shannon mentioned to a policeman that he should also have been carrying a pocket watch. When the authorities produced it, she opened the case—and there, inside the cover, was her picture staring back at her.

As proof that some people never learn and have no shame, one of the owners (the two being known at the time as “The Shirtwaist Kings”), Max Blanck, was arrested two years later, in 1913, for locking a door at his 5th Avenue factory during working hours.

In 1914, he was caught again—this time, his company was sewing counterfeit Consumer’s League labels into its garments. These labels were supposed to guarantee that the garments had been produced in safe workplace conditions. The ironic thing about these later transgressions by Blanck is that the Triangle Fire was the catalyst for many of the legal reforms which had been instituted in subsequent years. The reason people wanted to be assured a garment was produced in safe workplace conditions was precisely because of the tragedy at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. For example, laws were passed that called for automatic sprinklers in high-rise buildings, and for mandatory fire drills to be conducted in large shops. Doors had to be unlocked during working hours, and swing outward. Blanck never got the point, or simply didn’t care.

When the Triangle workers understandably went on strike in 1909, the Blanck and Harris hired thugs (some of them policemen) to beat the women up, and paid off politicians to turn a blind eye to their nefarious scoundrelisms.

When the fire broke out, the owners were on the top floor. They escaped the towering inferno by going up to the roof and then jumping to an adjacent building. They didn’t take the time to go back and tell the workers about the way to safety. It’s “funny” how that works.

Blanck and Harris were charged with manslaughter, but as so often happens with the wealthy and well-connected, they were found innocent of culpability.

In Book 2 of the “Taterskin & The Eco Defenders” trilogy (“Tell It to Future Generations”), the protagonist, Taterskin (a Labrador Retriever) and his animal and human friends travel back in time to prevent the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire from occurring; this is found in chapters 28 through 33, in particular. Chapter 28 can be found here.

Questions: Did Blanck and Harris pay anything to the family of the victims, or to the survivors? Did they collect insurance money from the fire? How did the rest of their lives turn out? Is it a stretch to call Blanck and Harris the Sacklers of the 20th Century?

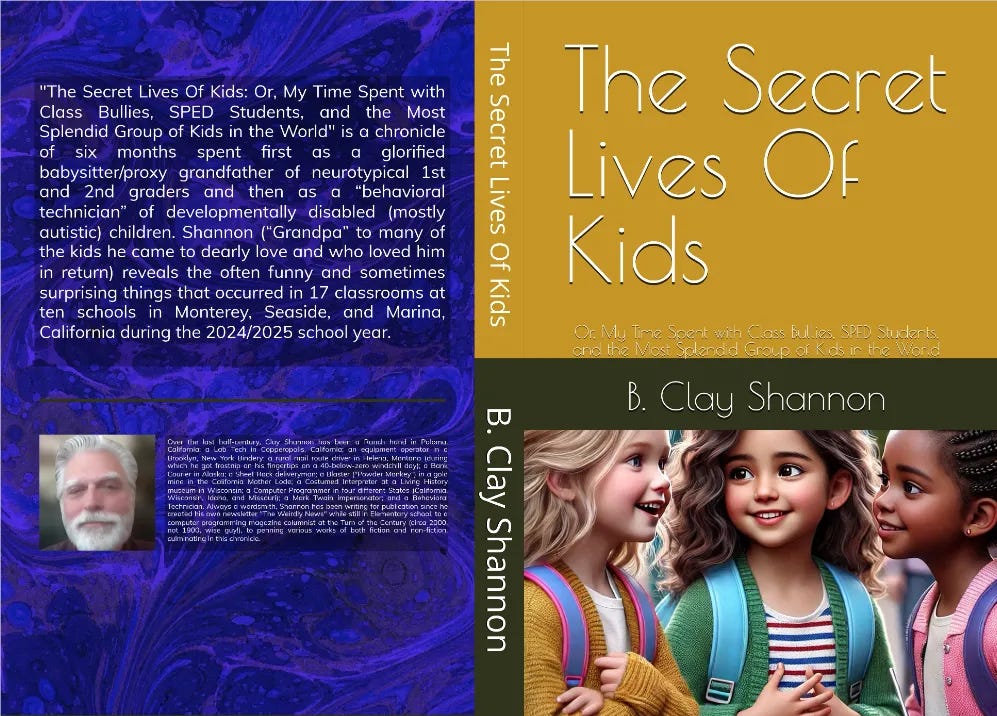

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.