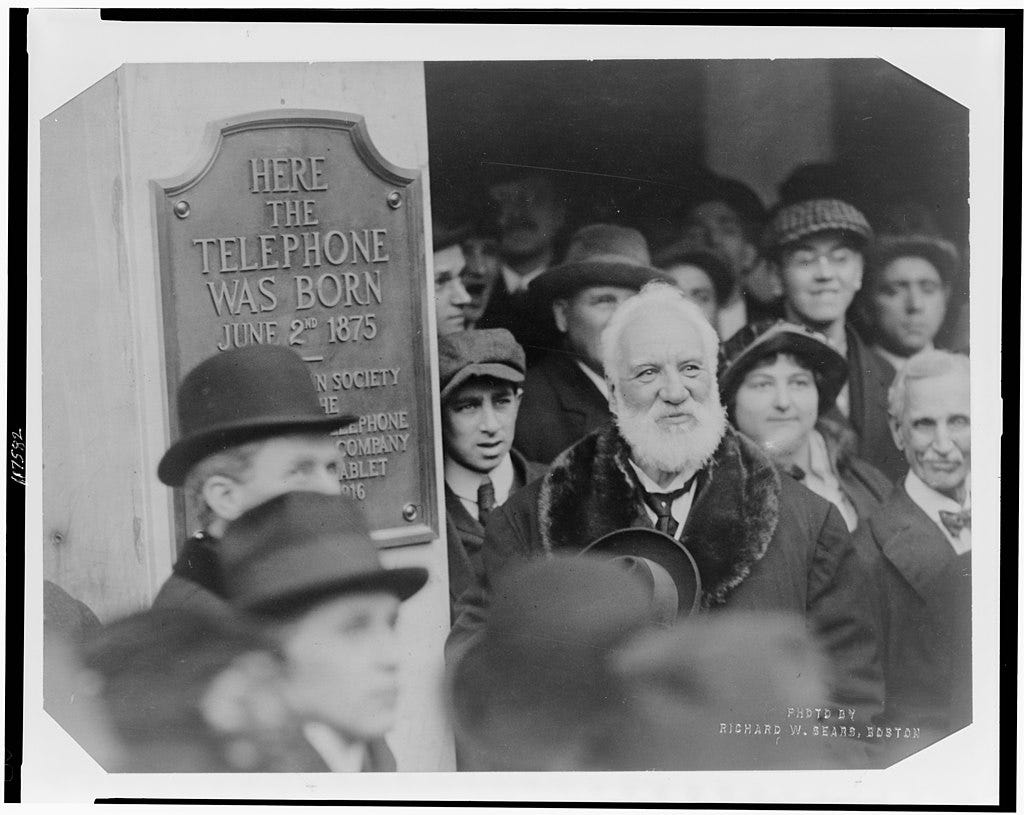

1876 — A.G. Bell’s Telephone Patented

public domain image from wikimedia commons

On this date in 1876, Scottish-Canadian-American inventor Alexander Graham Bell patented his invention, the telephone. Bell beat out fellow inventor Elisha Gray by a smidgen: Gray filed for a telephone patent just a few hours later. Close, but no monopoly.

Three days later, on March 10, Bell spoke over the telephone for the first time, to his assistant Thomas Watson (not to be confused with Sherlock Holmes' sidekick John H. Watson). Even though Watson was in another room of the same building, Bell used his newfangled contraption to say to his protege, “Mr. Watson, come here; I want you.”

Many felt Bell’s device was impressive, but would not be practical or come into general usage. One of these doubters was Mark Twain, who invested in many things that didn’t pan out, but refused to invest in the telephone, having that same pessimistic outlook for the device. Twain changed his mind (sort of) later, though, and was one of the first private citizens to have a telephone in his home.

Nevertheless, he was critical of the way the phone companies ran their businesses, a sentiment you may still agree with almost 150 years later:

“One of the very most useful of all inventions, but rendered almost worthless & a cold & deliberate theft & swindle by the black scoundrelism & selfishness of the companies of chartered robbers who conduct it.” — Mark Twain, on the telephone

Within a few decades of its invention, nearly everyone had a telephone in their home, attached to the wall. Now, most people carry their phone with them wherever they go.

The following is what I wrote about the invention of the telephone in chapter 1876: Reaping the Whirlwind of my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

“It is my heart-warmed and world-embracing Christmas hope and aspiration that all of us, the high, the low, the rich, the poor, the admired, the despised, the loved, the hated, the civilized, the savage (every man and brother of us all throughout the whole earth), may eventually be gathered together in a heaven of everlasting rest and peace and bliss, except the inventor of the telephone.”—Mark Twain

The telephone, a contraption which even its inventor Alexander Graham Bell despised as a nuisance, was invented this year. With a characteristic lack of prescience, many prognosticators thought the telephone would garner only a very limited number of users. One of these was Mark Twain. Although imbued with one of the sharpest minds in the nation, Twain was an almost ludicrously bad businessman. He was notorious for investing in business projects doomed to failure. Although investing fortunes in many “pie in the sky” ideas, Twain declined when the opportunity was offered him to invest in the telephone.

Twain was a proponent of most technology and an early adopter of gadgets such as the typewriter (he was reportedly the first author to submit a typewritten novel). In fact, Twain was even proud of the fact that he was the first private person to have a telephone installed in his residence. Nevertheless, he thought the device didn’t have much of a future—and more often than not hated the infernal contraption.

The first telephone directory contained just names and addresses, no telephone numbers — if you wanted to speak to someone, you called the operator and told them who you wanted to bother. The operator would then connect you with that person.

Another disadvantage of early telephones was that often many people shared the same line, and neighbors could—and often did—listen in on each other’s conversations. Widespread telephone usage had to wait until the Turn of the Century, though.

Questions: Why does the plaque in the picture above say June 2, 1875 rather than March 7, 1876? Have you read Mark Twain’s short story “A Telephonic Conversation”? Have you read Mark Twain’s short[ish] story “The Loves Of Alonzo Fitz Clarence And Rosannah Ethelton”? How many hours daily (on average) do you spend using your cell phone? Do you think cell phones are, all things considered, a good thing or a bad thing for society? In what ways are they good? In what ways are they detrimental?

1965 — Selma, Alabama’s “Bloody Sunday”

public domain images from wikimedia commons

Six hundred Civil Rights marchers were attacked by police in Selma, Alabama, on this date in 1965. As have other days of rage and violence, it became known as “Bloody Sunday.” Seventeen of the marchers were so severely injured that they had to be hospitalized.

The six hundred became first two thousand, then on a subsequent march 25,000 when Martin Luther King Jr. re-commenced the march later in the month, first on March 9th, and then again on March 25th. After President Lyndon Johnson (aka LBJ) supported the marchers, the U.S. military and FBI protected the marchers as they finally reached their destination of Montgomery, Alabama, the State Capital.

The following is what I wrote about directly related events in Alabama in chapter 1965: Fire, Fights, and Firefights in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up Like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore— And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over— Like a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load Or does it explode?

—from Langston Hughes’ poem “Harlem”

“I would rather die on the highway in Alabama than make a butchery of my conscience by compromising with evil … We’ve gone too far now to turn back.”—Martin Luther King, Jr.

On March 21st, a group of four thousand began a Civil Rights march that began in Selma, Alabama, and ended in that state’s capital of Montgomery. It was not a “walk in the park” for the marchers. One portion of the march, along the Jefferson Davis highway, was described this way in the book “Eyes on the Prize” by Juan Williams: As the marchers approached the far side of the [Edmund Pettus] bridge, Major John Cloud ordered them to turn back. “It would be detrimental to your safety to continue this march,” he said. “You are ordered to disperse, go home or to your church. This march will not continue. You have two minutes…” [Hosea] Williams asked, “May we have a word with you, Major?” Cloud replied that there was nothing to talk about. He waited, then commanded, “Troopers, advance.” Fifty policemen moved forward, knocking the first ten to twenty demonstrators off their feet. People screamed and struggled to break free as their packs and bags were scattered across the pavement. Tear gas was fired, and then lawmen on horseback charged into the stumbling protesters.

“The horses … were more humane than the troopers; they stepped over fallen victims,” recalls Amelia Boynton. “As I stepped aside from a trooper’s club, I felt a blow on my arm … Another blow by a trooper, as I was gasping for breath, knocked me to the ground and there I lay, unconscious…”

These depredations were all over the news, and decent Americans were outraged. Segregationists actually hurt their cause and hastened on legal redress. President Lyndon Johnson, in a televised speech, said of the Civil Rights proponents: “Their cause must be our cause, too. Because it’s not just Negroes, but it’s really all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.”

* * *

On August 6th, the Voting Rights Act was passed. Among its provisions, as enumerated by John Lewis in his book “Walking With the Wind” were:

• The suspension of literacy tests in twenty-six states, including Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi

• The appointment of federal examiners to replace local officials as voter registrars

• Authorization for the Attorney General to take action against state and local authorities that use the poll tax as a prerequisite to voting

As we will see in the 2000 chapter, though, the suppression of black votes was not completely done away with via this legislation. John Lewis certainly highly touts the Voting Rights Act. He goes on to write about the day the Act was passed: That day was a culmination, a climax, the end of a very long road. In a sense it represented a high point in modern America, probably the nation’s finest hour in terms of civil rights.

One writer called it the “nova of the civil rights movement, a brilliant climax which brought to a close the nonviolent struggle that had reshaped the South.” Yet, righteousness cannot be legislated. Hatred, prejudice, and violence cannot be gaveled out of cold, unreasoning hearts.

Less than a week later, the Watts Riots would begin. Lewis gives the reason for this spilling over of frustration and anger:

We now had the right to vote. We now had the right to eat at lunch counters. We could order that hamburger now … if we had the dollar to pay for it. Far, far too many of us, unfortunately, did not have that dollar. That was the challenge ahead of us now. Now that we had secured our bedrock, fundamental rights—the rights of access and accommodation and the right to vote—the movement was moving into a new phase, a far stickier and more complex stage of gaining equal footing in this society. The problem we faced now was not something so visible or easily identifiable as a Bull Connor blocking our way. Now we needed to deal with the subtler and much more complex issues of attaining economic and political power, of dealing with attitudes and actions held deep inside people and institutions that, now that they were forced to allow us through the door, could still keep the rewards inside those doors out of reach. Combating segregation is one thing. Dealing with racism is another.

1965 is considered to be the end of the modern Civil Rights era. What began with a Supreme Court victory in 1954 (Brown v. Board of Education) culminated with the Voting Rights Act just delineated.

Questions: How many of the 1965 marchers are still alive? Was it only black people who marched? How do you think history would have unfolded differently without the Civil Rights movement? Do you think racism will ever be completely eradicated? Do you think other forms of prejudice and discrimination will ever be completely eradicated?