“I don’t think that word [transcontinental] means what you think it means.” — The Princess Bride

1869 — Transcontinental Railroad Completed

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

America was becoming more proud of its technological achievements and scientific advances. Paralleling or mirroring such was the spirited drubbing that Mark Twain gave Europe and its pretensions in his first travel book, The Innocents Abroad, published this year. America was coming into its own, and now there were more opportunities than ever for Americans to see America.

After the north-south rent in the country had been provisionally patched up after the Civil War, the nation experienced horizontal unification. This binding of east and west came about as a result of the completion of the Transcontinental railroad.

The Golden Spike was driven into the tracks at Promontory Summit in Utah. This connected the Central Pacific tracks, laid primarily by Chinese working eastward from Sacramento, California, with the line laid by the Union Pacific, laid mostly by Irish workers heading west from Omaha, Nebraska.

The cross-tie into which the centennial spike was driven came from the Eel River country of northern California, where the Shannons were soon to live, and their relatives by marriage had already lived for some time.

The age of headlong expansion and innovation in the United States was not without its blemishes. Abuse of those who had done the actual work, which was hard and dangerous, was scandalous. The chickens came home to roost during the ceremony at Promontory Summit. It was a day of bloopers, truth be told:

First, Leland Stanford of the Central Pacific, one of the “Big Four” of that corporation—robber barons who charged whatever the market would bear as regards freight rates—almost failed to arrive for the ceremony due to—of all things—a train wreck.

Second, Thomas Durant of the Union Pacific was kidnapped on the way to the ceremony by some of his own employees, who had not been paid for months. The “photo op” had to be delayed two days (it was initially scheduled for May 8th). Durant was released only after he telegraphed for the money, received it, and disbursed it.

Third, Chinese laborers inadvertently gave a clear indication of how they had been treated away from the eyes of the public and the press when a photographer yelled “Shoot!” as they were lowering the last rail into place. On hearing that, the Chinese workers immediately dropped the rail and ran for the hills.

Fourth and finally, Stanford, attempting to drive the symbolic last spike (the golden spike which would subsequently be removed and replaced with a run-of-the-mill iron spike), failed to connect sledge with spike—twice. A laborer, sans frock coat, top hat, and boiled shirt, then stepped in and drove the spike home, finally making ends meet. The Iron Horse could now travel from coast-to-coast.

Crowds gathered in Washington, Philadelphia, and San Francisco awaited telegraphic word of the formal completion of the railroad link. When it was received, cheers erupted in all those far-flung places. In San Francisco, a great banner was unfurled, proclaiming “California Annexes the United States.”

In 1969, exactly a century later, Americans would be awed by technology again as they watched a pair of their countrymen take small but significant steps on the moon.

Many of the rail-builders working their way westward were Irish Civil War veterans. Most of those working their way eastward from California were Chinese, who were paid less and treated worse than their white co-workers.

It was hard work, exacerbated by the extremes in harsh weather they had to endure, and dangerous, too, due to avalanches and accidents with explosives. Still, they finished the project ahead of time and under budget. Cross-country travel time was reduced from weeks to days. Now, of course, we can fly cross-country in a matter of hours.

Questions: If you had been alive at the time, would you have considered taking a job helping lay the tracks? If you had been less in need of work and not of an adventurous bent, would you have been an “early adopter” of this new way of crossing the mountains in a fraction of the former amount of time it would have taken you? How much did a passenger ticket cost? What does that equate to in modern money? Does it make air travel seem like a bargain or a “ripoff”?

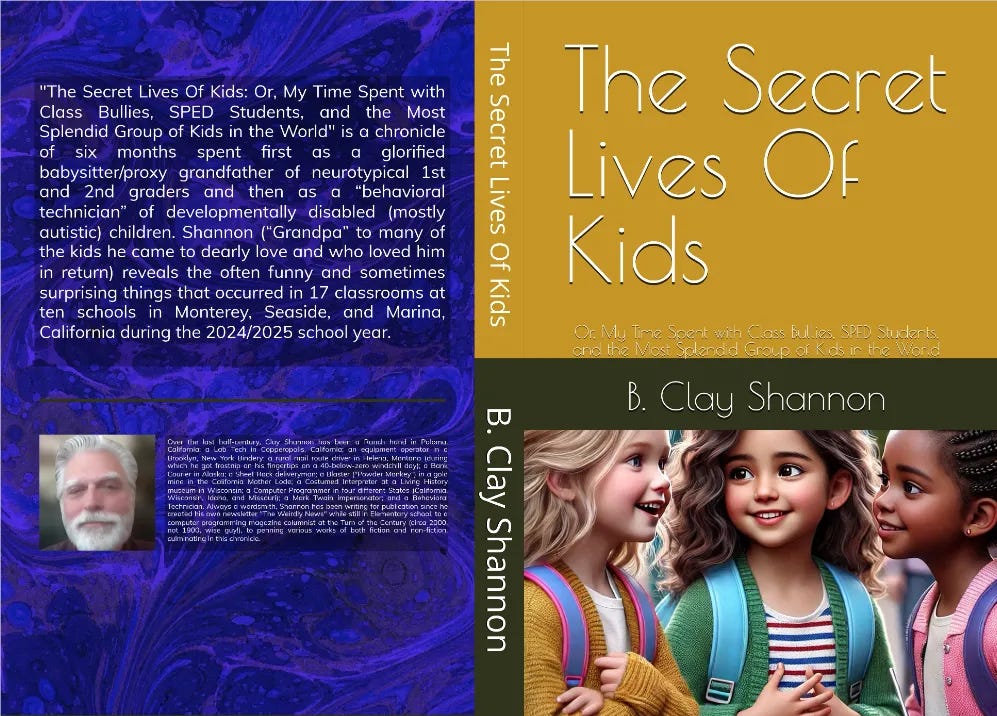

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.