The Mysteries of History (May 20 Edition)

Homestead Act; Blue Jeans Patented; Lindbergh's Transatlantic Flight

1862 — Homestead Act

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Abraham Lincoln wasn’t “Civil War, all the time” during that conflict. On this date in 1862, a little over a year after the start of that war, Lincoln signed the Homestead Act into law.

The Homestead Act enabled family heads 21 or older to acquire 160 acres of land and farm it. They were required to build a house on the land, and farm it for five years before it became theirs. Or, they had the opportunity to purchase the land for $1.25 per acre ($200) after six months.

It sounds like quite a bargain, but many people tried and failed to make a success of it. Farming on the frontier is not for the faint of heart. For those who gave up or were unsuccessful, the land returned to the government to again be made available to other farmowner-wannabes.

On the other hand, if the homesteader successfully made a go of his farming enterprise, the land was his after five years for an $18 filing fee (cheap at many times the price).

Homesteading had been proposed earlier, but Southern States and northern manufacturers opposed it, the Southern States because they feared the newly-opened areas would eventually become States that would oppose slavery, and the manufacturers because they thought they would lose their employees to this opportunity afforded them to be independent. Once the Civil War was being waged, though, the Southern States no longer had a say in which laws would be passed within the Union, so the time was ripe for Lincoln to shepherd this legislation through the process of becoming the law of the land. So, there was a Civil War connection to Lincoln’s investment of time in the Homesteading Act, after all.

Some took unfair advantage of the homestead act, abusing it for their own non-farming purposes; for example, companies interested in exploiting the land’s resources for commercial gain paid individuals to file homestead claims on their behalf, with the businesses ultimately owning the land themselves.

Sadly, but probably predictably, some Indian tribes lost their land when large swaths of the previously sparsely settled “West” was opened up to homesteading (what was considered the “West” has changed over time, with Missouri, for instance, once being considered the West).

If all this sounds “too good to be true” to you, it is now, as it’s too late to benefit from it: the Homestead Act was repealed in 1976, almost 50 years ago. The last claim, filed in 1974 for a “half-sized” plot of 80 acres was “proved up” (in Alaska) in 1979.

The first person to file a claim was Civil War veteran Daniel Freeman, on January 1, 1863. The last, just alluded to, was also by a (Vietnam) veteran, Kenneth Deardorff.

The following is what I wrote about the Homestead Act in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

“There are at all times hundreds of families in the old eastern and middle states who long to leave that depleted, worn-out land and come to the West…”— from “A Sketch of the City and its Attractions—A Picture Made up of Facts, not Fancies—Our Business Enterprises and Business Men” from the Dec. 4th, 1869 issue of the “Jersey County Democrat”

. . .

Thomas Jefferson had a dream. It was that America should become a nation of tradesmen and yeoman (independent farmers). This desire, which was also held by other Americans, was reflected in the Homestead Act. Passed thirty-six years after Jefferson’s death, and signed on May 20th of this year by Abraham Lincoln, it allowed men to claim 160 acres of “unappropriated pub lic lands.” After five years of living on the land and improving it (building houses and barns, farming it), the land would become theirs for a ten dollar filing fee.

Alternatively, for those with more money than patience, they could purchase the land for $1.25 per acre after living on it for just six months.

A homestead was granted to “any person who is the head of a family, or who has arrived at the age of 21 years, and is a citizen of the United States, or who shall have filed his declaration of intention to become such.” It will prob ably not surprise anyone that some scoundrels found loopholes to get around the legalities. The worst transgressors, the most vile frauds of all, were those who were not needy—big railroad and mining companies.

Much of the land east of the Mississippi was already privately owned by this time, so homesteaders for the most part—as was the intent of the law—had to cross the mighty River and help to win the West.

After being expanded in 1909, the Homestead Act was repealed in 1976.

Questions: Do you know anybody who homesteaded? Did any of your ancestors homestead? If the Homestead Act was still in effect, would you consider taking advantage of it? If so, where would you want to start your farm?

1873 — Levi Strauss & Co. Corner the Market on Blue Jeans

public domain images from wikimedia commons

On this date in 1873, a San Francisco businessman (Levi Strauss, 1829-1902) and a Reno, Nevada tailor (Jacob Davis, 1831-1908) teamed up to patent durable work pants, now commonly referred to as “Blue Jeans.” It was Davis who came up with the idea to reinforce the garment at its “stress points” with metal rivets.

Davis had the idea, but not the money to apply for the patent. Strauss, already a successful businessman catering to the gold miners in California, had the cash. Together they received the patent for the rather dull and not overly descriptive “Improvement in Fastening Pocket-Openings.”

Davis oversaw the manufacturing of the garments, with seamstresses working out of their homes to produce what were first called “Waist Overalls.” In 1880, Strauss opened a factory to churn out the popular work pants. By the 1920s, the denim “Levis” were the top-selling work pants for men in the U.S.

The popularity of Levi’s jeans only increased over time — they are no longer just for men, and they are no longer just for work, and probably haven’t been for your entire lifetime.

Questions: How many pairs of Levi blue jeans have you owned in your life? When did the “501” model first become available? How long were Strauss and Davis affiliated with each other? Where were Strauss and Davis born? Have you heard the illogically titled song Red Blue Jeans And A Pony Tail by Gene Vincent? Have you heard the song Denim Demon from the British blues-rock band great Savoy Brown’s Lion’s Share album?

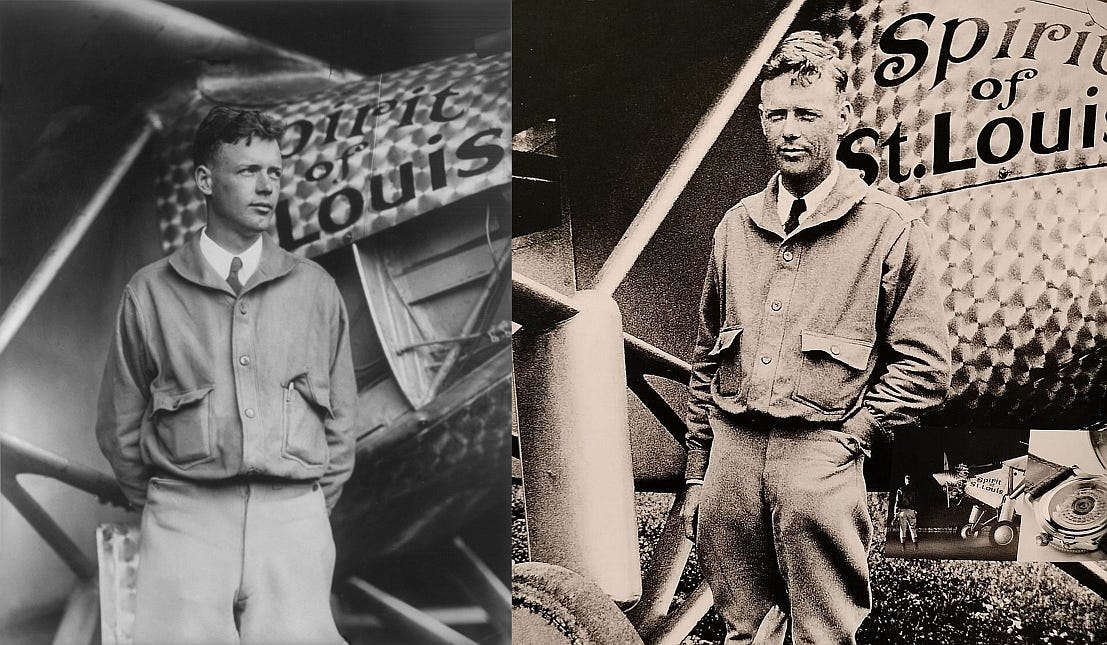

1927 — Charles Lindbergh Flies to Paris for Fame & Fortune

public domain images from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about Lindbergh’s Solo Transatlantic flight in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

St. Louis, Missouri, is located at just about the midway point of the Mississippi River, where the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers meet, mix, meld, and eventually mesh. Aviator Charles Lindbergh flew The Spirit of St. Louis on the first solo Transatlantic flight this year. “Lindy,” after not being able to sleep the night before due to a superabundance of nervous adrenalin, began his flight on May 20th from New York. Exhausted, he ended it amidst an ecstatic crowd at the Paris airport the next day.

Charles Lindbergh and his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh would suffer heartbreak as an indirect result of their fame and fortune in the near future—more on that in the 1934 chapter.

Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974) did not come up with the idea for the flight on his own. He entered a competition to complete the nonstop solo journey which paid $25,000 to the winner.

Lindbergh was from Detroit; he named his plane for his sponsor, the St. Louis, Missouri, Chamber of Commerce. His trip almost ended before it really got underway, as his plane, at its maximum weight due to its full fuel tank, barely cleared the telephone wires at the end of the runway at Roosevelt Field.

As he had not slept the night before, Lindbergh had a hard time remaining awake for the duration of the flight. The featureless and lightless seascape below him probably didn’t help matters. So overwhelming was his drowsiness that he held his eyes open with his fingers and even hallucinated (thinking he saw ghosts flitting through the cockpit).

After a flight lasting over 33 hours, and being awake for two days, Lindbergh landed at Le Bourget field in Paris to cheering crowds. After a total of 55 hours awake, “Lucky Lindy” finally got some shuteye.

Questions: Have you read Lindbergh’s book The Spirit of St. Louis? Have you read A. Scott Berg’s Pulitzer-prize winning Lindbergh? Have you ever flown in a private plane? Have you ever piloted a plane? If not, would you like to?

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.