The Mysteries of History (May 28 Edition)

Andrew Jackson Dislocates the Indians (Trail of Tears); Steinbeck's Tortilla Flat

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” — Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana, 1905

“He is free to evade reality, he is free to unfocus his mind and stumble blindly down any road he pleases, but not free to avoid the abyss he refuses to see.” — Alice O’Connor, 1961

1830 — Andrew Jackson Evicts Indians From Their Land

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

“This country has come to feel the same when Congress is in session as when the baby gets hold of a hammer.”—Will Rogers

“The way, and the only way, to check and to stop this evil, is for all the Redmen to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land, as it was at first and should be yet; for it was never divided, but belongs to all for the use of each. That no part has a right to sell, even to each other, much less to strangers—those who want all and will not do with less.”—Tecumseh, Shawnee Chief

“I have heard that you intend to settle us on a reservation near the mountains. I don’t want to settle. I love to roam over the prairies. There I feel free and happy, but when we settle down we grow pale and die.”—Satanta, Kiowa

“Their reason for killing and destroying such an infinite number of souls is that the Christians have an ultimate aim, which is to acquire gold, and to swell themselves with riches in a very brief time and thus rise to a high estate disproportionate to their merits. It should be kept in mind that their insatiable greed and ambition, the greatest ever seen in the world, is the cause of their villainies.”

—Bartolomé de Las Casas, writing of Columbus in 1542

“As for anyone repaying bad for good, bad will not move away from his house.”—Proverbs 17:13

“Man is the Only Animal that Blushes. Or needs to.”—Mark Twain

. . .

Some view 1830 as the beginning of the Victorian Era. Depending on which authority you give credence to, that era would end in either 1900 or 1915. For those who view 1900 as the end of the Victorian era, they view the period from 1900–1910 as being the “Edwardian” age (Queen Victoria was replaced on the throne by her son, Edward VII, in 1901).

A gilded age of sorts seized the state of Georgia beginning in 1828: gold was discovered on land owned by Cherokees. Whenever precious resources have been discovered in the United States, it has usually indicated that an upheaval was in store for any natives who lived on the valuable land. This continued a pattern begun way back in 1492 in the Americas, when Columbus discovered gold in San Salvador and forced the natives to bring it to him—or else.

Yes, the white man’s lusty obsession for gold has meant disenfranchise ment, loss of land, and loss of life, even complete extermination at times, for the natives of the Americas. This has been the case beginning with Columbus’ genocidal ransacking of Haiti (known then as Hispaniola, and later as Saint Domingue). James Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me comments on this pattern:

The Santa Maria ran aground off Haiti. Columbus sent for help to the nearest Arawak town, and “all the people of the town” responded, “with very big and many canoes.” “They cleared the decks in a very short time,” Columbus continued, and the chief “caused all our goods to be placed together near the palace, until some houses that he gave us where all might be put and guarded had been emptied.” On his final voyage Columbus shipwrecked on Jamaica, and the Arawaks there kept him and his crew of more than a hundred alive for a whole year until Spaniards from Haiti res cued them.

So it has continued. Native Americans cured Cartier’s men of scurvy near Montreal in 1535. They repaired Francis Drake’s Golden Hind in California so he could complete his round-the-world voyage in 1579. Lewis and Clark’s expedition to the Pacific Northwest was made possible by tribe after tribe of American Indians, with help from two Shoshone guides, Sacagawea and Toby, who served as interpreters. When Admiral Peary discovered the North Pole, the first person there was probably neither the European American Peary nor the African American Matthew Henson, his assistant, but their four Inuit guides, men and women on whom the entire expedition relied. Our histories fail to mention such assistance. They portray proud West ern conquerors bestriding the world like the Colossus at Rhodes.

Following that pattern, the effect of the discovery of gold in Georgia made the land suddenly attractive to Euro-Americans. This paved the way for the Indian Removal Act passed by Congress this year. “Indian Removal” was a euphemism for heartless eviction. A gold brick road for whites to the Indians’ land, a road of muck, sharp jagged rocks, and blood for the Indians, who would be disenfranchised and dispossessed as a result. This was nothing new, just a new garment cut from the same old cloth in the same old pattern. Way back in 1758, Britain had promised Indians that they would prohibit white settlement west of the Alleghenies; later, this promise was changed to the Appalachians. And that red/white boundary kept getting pushed further west by the United States government.

Andrew Jackson, the old Indian fighter who was called “the Devil” by many of the land’s original inhabitants, made Indian Removal a key issue in the 1828 Presidential Campaign.

Jackson, who won the election and took office in 1829, thought that America’s frontiers would always remain such (a bad thing, to his way of thinking), as long as Indians were around. He would have gladly exterminated them completely in an act of “ethnic cleansing,” but world opinion made extermination of the pesky red race impossible. They would have to be uprooted instead.

So it was that this year Congress passed the “Indian Removal Act” by a vote of 102-97. Its official name was the euphemistic “An Act to Provide for an Exchange of Lands with the Indians Residing in Any of the States or Territories, and for Their Removal West of the River Mississippi.”

In his book “Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors,” Stephen Ambrose showed that such had been the pattern since the beginning in America:

From the time of the first landings at Jamestown, the game went something like this: you push them, you shove them, you ruin their hunting grounds, you demand more of their territory, until finally they strike back, often without an immediate provocations so that you can say “they started it.” Then you send in the Army to beat a few of them down as an example to the rest. It was regrettable that blood had to be shed, but what could you do with a bunch of savages?

The feeling among whites at the time was that the lands acquired via the Louisiana Purchase consisted partly of land unwanted by the Euro-Ameri cans, and as such would prove a handy location to stash the Indians. One problem was, though, that there were already some Indians living there (as was the case all across the continent). It was determined that the eastern Indians would be “bought out” and driven westward to Indian Territory, roughly corresponding to modern-day Oklahoma.

Thirty-seven cents an acre was a typical price paid the Indians by the government for land obtained from them by treaties. The Indians, for the most part, were given to understand they really didn’t have any choice in the matter. They would move voluntarily or otherwise, so they may as well take the little bit they were offered and make the most of it. Sometimes the government agents found it to their advantage to first ply the Indian representatives with alcohol before pressuring them to conclude the terms of the sale.

It got even worse, though: From 1840 to 1850 the government acquired approximately 20 million acres from the Indians at a cost of approximately $3 million, or what ended up averaging out to a measly fifteen cents per acre—recall that the going price for land was $1.25 per acre if bought from the government, more if purchased from private parties.

Secretary of War Lewis Cass wrote in an 1830 article promoting Indian removal: “…The progress of civilization and improvement, the triumph of industry and art, by which these regions have been reclaimed, and over which freedom, religion, and science are extending their sway…A barbarous people, depending for subsistence upon the scanty and precarious supplies furnished by the chase, cannot live in contact with a civilized community.”

Just in case there is any confusion about the matter, when Cass referred to a “barbarous people,” he meant the Indians. The “civilized community” of which he spoke was, supposedly, the Euro-Americans. Just five years before writing that article, Cass had promised the Indians, at a treaty council with Shawnees and Cherokees, regarding land the Indians were being given: “The United States will never ask for your land there. This I promise you in the name of your great father, the President. That country he assigns to his red people, to be held by them and their children’s children forever.” This promise (naturally) was broken.

While Indians were being forced out of the South to the West, blacks in the South were being forced to remain in the South. Not all blacks docilely accepted their fate; some fought against it. Some fought directly, like Nat Turner, who led a slave rebellion the year after this (more on that in the 1831 chapter). Others combated slavery by fleeing the South via a network of trails, “stations” (safe houses) and “conductors” (guides), which were collectively called the Underground Railroad.

As a counterpoint to Mr. Cass, quoted above, let us once more parade forth Mark Twain. In his essay “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” written in 1901, he was referring to the situation in the Philippines, but it is apropos when dealing with the Indian and Negro situations discussed here, as well as of many others both before and since. Twain used his “pen warmed up in hell” to write:

Shall we? That is, shall we go on conferring our Civilization upon the peoples that sit in darkness, or shall we give those poor things a rest? Shall we bang right ahead in our old-time, loud, pious way, and commit the new century to the game; or shall we sober up and sit down and think it over first? Would it not be prudent to get our Civilization tools together, and see how much stock is left on hand in the way of Glass Beads and Theology, and Maxim Guns and Hymn Books, and Trade Gin and Torches of Progress, and Enlightenment (patent adjustable ones, good to fire villages with, upon occasion), and balance the books, and arrive at the profit and loss, so that we may intelligently decide whether to continue the business or sell out the property and start a new Civilization Scheme on the proceeds?

By the end of his Presidency (1829-1837), Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson (1767-1845) was behind 70 mass deportations of Indians, with the government confiscating 25 million acres of their land, which was subsequently used for the expansion of slavery in the South. Thus, Jackson’s Machiavellian maneuverings and manipulations harmed both the Native Americans and the Blacks, yet his visage still adorns the $20 bill.

public domain images from wikimedia commons

Image generated by Google Gemini

Questions: Where was Andrew Jackson from? What role did Jackson play in the War of 1812? How did he get the nickname “Old Hickory”?

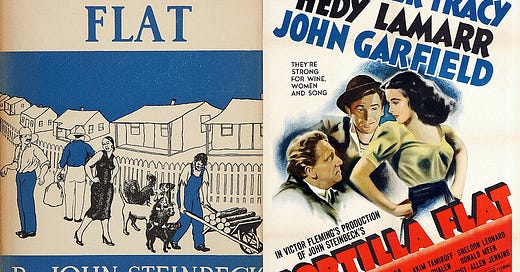

1935 — John Steinbeck’s First Well-Received Novel

public domain images from wikimedia commons

John Steinbeck (1902-1968) published the uproariously funny (Twainesque, in fact) novel Tortilla Flat in 1935. It was published on this date that year.

The hilarious scenes in Tortilla Flat were based on, or inspired by, events from his native Monterey County, California. It was made into a movie in 1942.

Other notable works of Steinbeck’s (many of which were also silverscreenerized) include The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, East of Eden, The Wayward Bus, The Pastures of Heaven, The Long Valley, The Red Pony, In Dubious Battle, The Winter of our Discontent, Cannery Row, and the travelogue Travels With Charley: In Search of America.

Questions: What is your favorite John Steinbeck novel? What is your favorite movie or miniseries made from a John Steinbeck story?