“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” — Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana, 1905

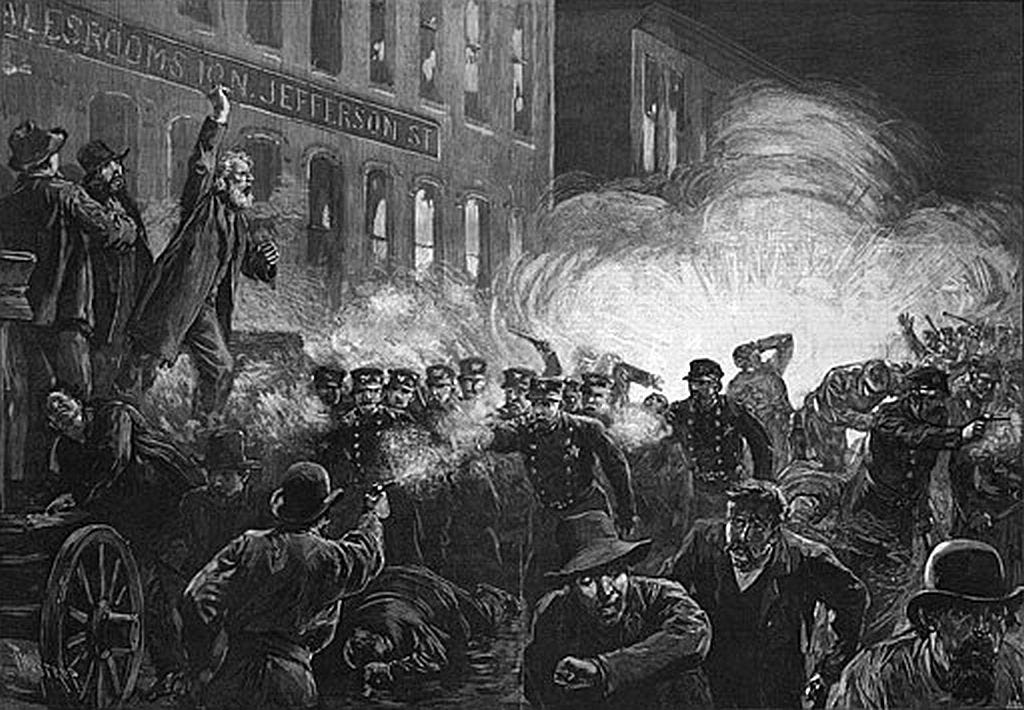

1886 — Haymarket Square Riot

public domain image from wikimedia commons

It’s not possible to provide a definitive explanation of what happened at Haymarket Square in Chicago on this date in 1886, as the opposing sides’ stories are so different. According to the activists who had gathered to protest police brutality, the violence was all the fault of the police. The police had a diametrically opposed view as to who instigated the mayhem. Likely there was culpability on both sides, even if it was just a few bad actors on each side.

Several on both sides died in the melee (bomb-throwing and gun-firing), and several others were subsequently executed for their role in the riot. It is telling, though, that three of the protesters who were initially condemned to die had their sentences adjusted to life in prison by the Governor of Illinois and then, possibly partially due to widespread feeling among the public about their being innocent of serious wrongdoing, the three were fully pardoned in 1893 by the next Governor.

Questions: Why is it that there are differing accounts of who was responsible for the several deaths and almost 100 injuries during the protest? What happened to the three pardoned men during the rest of their lives? Did this event affect other cities as well?

1961 — First “Freedom Ride” for Civil Rights Begins

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the Freedom Riders in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

CORE(Congress Of Racial Equality) organized an invasion of the south to test the new law and thus set a precedent for future response by the author ities to any who wanted to exercise their rights in this regard. The core (no pun intended) intent of the action was to dramatize segregation in the South and to see to it that the new law did not exist solely on paper but would indeed be enforced.

This was actually not the first ride of its type, or with the same purpose. A similar one had taken place fourteen years earlier, in 1947. That trip, also made by bus, was termed the Journey of Reconciliation, and was also under taken in response to a law which made segregation on interstate buses illegal (not in the bus terminals, but just on the buses themselves). That first trip, which planned to make a tour of the “Upper South” states of Virginia, Kentucky, and North Carolina, ended when twelve of the riders were arrested in North Carolina for violating a state segregation law, for which they were sentenced to serve twenty-two days on a chain gang.

In his book “Walking With the Wind,” John Lewis explains why this action was taken:

The federal government was not enforcing its own laws in that section of the coun try because of fear of political backlash from those states. If, in some way, it might become more politically dangerous for the federal government not to enforce those laws than to enforce them, things would begin to change. If, for example, those states were forced to visibly—even violently—defy the law, with the whole nation looking on, then the federal government would be forced to respond in ways it had not so far.

The plan was that after three days of training, those who were selected to be a part of the momentous event would board buses in Washington, D.C. and make stops in Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. They were scheduled to arrive in New Orleans on May 17th, the seven year anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision.

They didn’t make it that far. Things went even worse for many Freedom Riders than they had gone for those on the Journey of Reconciliation in 1947, who had toiled on the chain gang.

A Greyhound bus carrying nine Freedom Riders was bombed in Anniston, Alabama. After comparing the scene to something you might expect to see in World War II, Bosnia, Verdun, or Antietem, John Lewis describes what happened:

But this was America in 1961. Those were American men who had clutched pipes and clubs and bricks as they surrounded that bus when it had pulled into the Anniston terminal that day. Those were Americans shouting and cursing and beating on the windows with their crude weapons. It was all the driver could do to gun the engine and hurriedly back the vehicle out. And even then, someone got to the rear tires and slashed them before the bus managed to pull away.

It had sped west, its back tires flattened, with an army of fifty cars and pickup trucks in hot pursuit. It was like something out of a horrible movie.

After six miles the bus had rolled to a stop, its tires worn down to the rims. The driver threw open the door and ran, as one witness later described it, “like a rabbit.”

Meanwhile the mob arrived, two hundred of them, circling the bus and smashing the windows. They tugged at the door, which had been pulled shut. They screamed at the riders, who were sprawled on the floor of the bus, avoiding the flying glass.

Then someone in the crowd hurled a firebomb, a Molotov cocktail, through the back window. As thick smoke and flames began to fill the bus, the riders rushed to the door and found they couldn’t open it. The mob was now pushing the door shut, trapping the people inside.

At that point a passenger in the front seat of the bus pulled a pistol and waved it at the crowd outside. He was a white man. His name was Eli Cowling. He was an Alabama state investigator who had been traveling undercover to keep an eye on the riders. Now it was no longer a priority for him to keep his identity secret. His life was on the line along with everyone else’s on that bus.

The crowd backed off. Out the emergency exit door, led by Al Bigelow, tumbled the riders, choking and coughing. One by one they fell to the grass, the last one climbing out just as the bus was rocked by a blast—the fuel tank exploding. Now the mob moved in, still cautious because of Cowling’s pistol, but pecking around the edges, like birds darting at a wounded animal. Henry Thomas, whose large size was usually a deterrent, was clubbed as he staggered away from the bus; somebody swung a baseball bat into the side of his head. Genevieve Hughes had her lip split open. Rocks and bricks were heaved from people in the crowd too afraid to come closer.

That was not the only violence in Anniston that day, though. A Trailways bus, which pulled into the terminal an hour later, was also attacked.

And in Birmingham, Alabama, the attack was even more vicious.

Years later, testimony presented before the U.S. Congress described local Ku Klux Klan leaders conferring with Birmingham police and receiving a promise from them that the police would give the Klan ample time to wreak havoc before the police finally made a belated show of establishing order. When asked on that day, though, why the police had been so slow to respond, Birmingham Chief of Police Eugene “Bull” Conner had given the excuse that it was Mother’s Day and that “We try to let off as many of our policemen as possible so they can spend Mother’s Day at home with their families.”

A mixed-race group of thirteen young people began a bus ride from Washington, D.C. by bus en route to Louisiana on this date in 1961. They were protesting the non-compliance of southern States regarding segregation on buses. They never arrived at their destination. The furthest south they got was Jim Crow Jackson, Mississippi. In South Carolina and in Alabama, they faced vicious crowds led by KKK members who took offense at the blacks and whites mingling on the bus, even sharing seats with each other in black-white pairs. They had to be evacuated from Jackson for their own safety.

But other buses of Freedom Riders followed. After much weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth, a strong enough spotlight was shown on the southern mired-in-the-muddy-and-bloody-past Jim Crowers that segregation was finally established.

Questions: Have you heard of the the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation? What connection does it have with this event?

1970 — Four Dead in Ohio

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the Kent State tragedy in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

Tin soldiers and Nixon’s comin’.

We’re finally on our own.

This summer I hear the drummin’.

Four dead in Ohio.

—from the song “Four Dead in Ohio” by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young

“Sayin’ it’s your job don’t make it right, Hoss.”

—Paul Newman as Lucas “Luke” Jackson in the movie “Cool Hand Luke”

At Kent State, near Akron, Ohio, students were interfering with military recruitment efforts on campus. The Ohio National Guard was sent in to pre vent such interference from continuing. Their mission was to make the cam pus safe for recruiters. Somewhat similar to the situation eight years earlier at Ole Miss in Oxford, Mississippi, tensions escalated over the question of who should be allowed on campus.

It is quite possible that many of the Guardsmen did not want to be there and felt no animosity toward the students. As was the case with many mem bers of the Mississippi State Militia called in to quell the disturbance at Ole Miss in 1962, these guardsmen didn’t necessarily agree with their orders but followed them nonetheless.

Despite any sympathy some of the Guardsmen may have felt for the stu dents or their cause, certain of their number opened fire on the students pro testing the Vietnam War. Four students were killed. Crosby Stills Nash & Young wrote a song about the incident.

The most widely known photo of the event [shown above] depicts a visibly distraught young woman bending over an apparently dead young man. Most assume, no doubt, that the young woman was a student at Kent State. In fact, she was not; she just happened to be passing through. The despair and disbelief her posture seemed to evoke represented the way most people reacted to the situation. Why are we killing our own? What had the students done deserving of death? Where does it all end? How can such tragedies be prevented from happening again? Did the punishment fit the crime?

Who were the National Guard guarding when they killed unarmed pro-Peace demonstrators? Never underestimate the power of peer pressure: How many of the National Guardsmen, who attached bayonets to their rifles before advancing on the students, may have had sympathetic views toward the protesters?

Charges were brought against eight of the Guardsmen, who had not fired a warning shot before opening up on the crowd with a barrage of bullets, but four years later, in 1974, all of the charges were dropped.

Questions: Have you heard the song Ohio by CSN&Y quoted from above? Does the government have the legal right to curtail peaceful protests? Did any of the Guardsmen have family members or friends in the group of protesters?

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.