The Mysteries of History (May 7 Edition)

Lusitania Sunk in WW1; Germany's WW2 Surrender; Agent Orange in Vietnam

“He is free to evade reality, he is free to unfocus his mind and stumble blindly down any road he pleases, but not free to avoid the abyss he refuses to see.” — Alice O’Connor, 1961

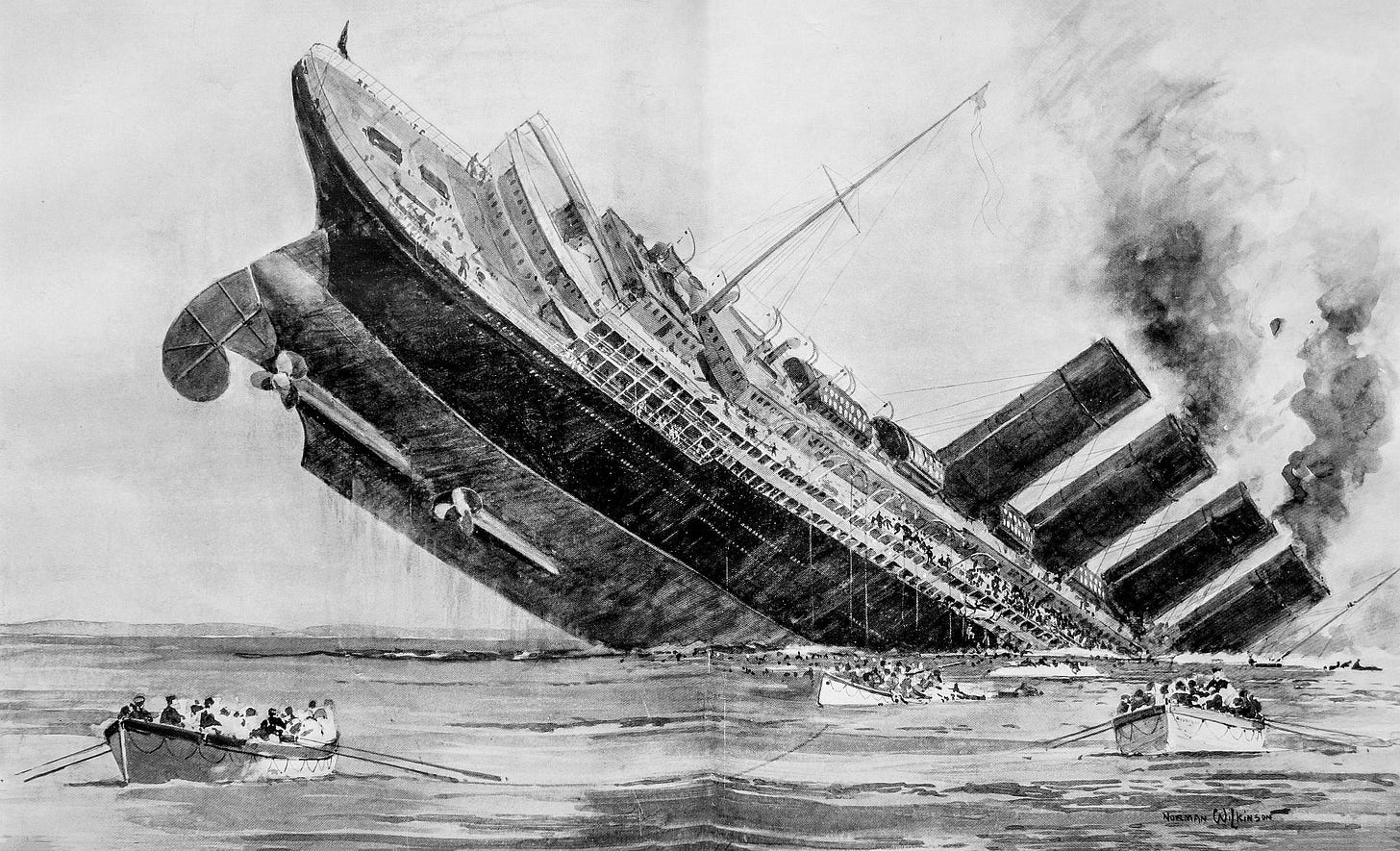

1915 — Lusitania Sunk by German Submarine During World War 1

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The Lusitania was a British passenger ship (ostensibly, at any rate). It was torpedoed off the coast of Ireland by a German submarine on this date in 1915, early on in the so-called “Great” War (later redeviled [rather than rechristened] World War 1).

More than half (1,198) of the 1,959 people aboard drowned as a result — the ship sank so quickly (in 20 minutes) that rescues were only possible for a minority of the travelers.

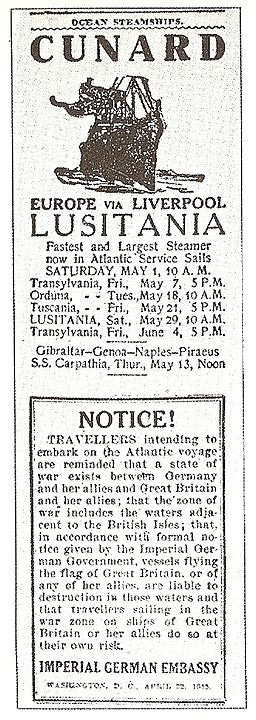

The ship was not explicitly warned ahead of time (on that day, anyway); actually, the Germans had warned that they would make themselves free to attack all ships — of any sort — in the area. The German Embassy in Washington, D.C., even went so far as to publish a warning in U.S. newspapers that passengers on British ships or those of their allies embarked at their own risk, the warning even appearing right next to the advertisement of the Lusitania sailing:

This warning does not absolve the German government and military of that time of guilt, of course, though. They were not obligated to murder over 1,000 people, most of them civilians.

It eventually came to light that the Lusitania was not just a pleasure cruise for pilgrims wanting to expand their horizons — on board were 173 tons of munitions bound for use by the British, something the Germans were apparently aware of. Were all of the passengers aware of that, though?

The ship’s captain was partly at fault for the disaster, too, because he had also been warned of the danger by the British government to either avoid the area or at least use diversionary tactics, such as tacking in a zig-zag, or serpentine, fashion. He bull-headedly refused, and paid the consequences — that is to say, 1,198 of his passengers did: he himself did not go down with his ship, but lived almost two more decades, until 1933.

Germany’s attacks on vessels around Britain provoked the ire of the U.S., who had previously been staunchly neutral in the war, because Britain was a chief commercial partner of the U.S., and so Germany’s sinking of vessels traveling between the U.S. and Britain was harming U.S. moneyed interests. Thus, America eventually prepared for, and then later entered, the war.

The following is what I wrote about the Lusitania in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

America was not yet officially involved in “The Great War” when some of its citizens were passengers on a journey from New York to Liverpool on the luxury liner Lusitania. Attacked by a German submarine on May 7th, the Lusitania did not dawdle in its descent to the depths of the sea. A mere eighteen minutes after being struck, it vanished beneath the ocean’s surface. One thousand one hundred ninety eight men, women, and children perished. Among these victims were one hundred twenty-four Americans.

The incident did not come as a complete shock. The German government had advertised in New York papers, warning Americans against traveling on British ships. Postcards of the ship sold dockside prior to the departure of the Lusitania bore the gallows-humor caption “Last voyage of the Lusitania.”

Although Germany offered apologies and reparations for the Americans killed, outrage over the incident played a large role in getting America directly involved in The Great War.

Americans’ view towards Germans changed drastically after this incident. Although at the turn of the century 1/10th of Americans spoke German (about the same ratio of Americans who now, a century later, speak Spanish), after this incident many with German surnames changed them to less Teutonic sounding ones, and some place names changed, too (from, for instance, Berlin to Oberlin). Frankfurters started being called “hot dogs.” Also, similar to French fries “morphing” into “Freedom fries” in 2003 after France refused to support America’s invasion of Iraq, sauerkraut began being called “liberty cabbage.

* * *

News of the Lusitania tragedy could be relayed quickly across the country, using the newly available Transcontinental U.S. Telephone Service, which had begun operation January 25th.

Questions: If you had booked passage on the Lusitania and then saw the warning from the German Embassy in the newspaper, would you have still gone? If you had opted to remain home, would you have been able to get a refund on your ticket? What if the rest of your traveling party were unworried, and called your courage into question — would you acquiesce and go along, even though you felt endangered? If so, how would you have felt about them and yourself once the ship was hit and began to sink?

1945 — Germany’s Unconditional World War 2 Surrender

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Exactly 30 years after the sinking of the Lusitania near the start of World War 1, World War 2 ends on this day in 1945 in Europe as the Germans surrender unconditionally, a la Lee to Grant four score of years earlier at the end of the Civil War in 1865.

It wasn’t Hitler that surrendered; he had taken the coward’s way out by killing himself, which was doubtless the least despicable murder he was ever involved in. Nor was it any of the other “big name” Nazis who cried “uncle [Sam]”; it was the relatively unknown Alfred Jodl who put pen to paper admitting utter defeat for the Nazis.

A year-and-a-half later, Jodl was hanged for war crimes.

Questions: What bone was thrown to Jodl’s bones seven years after he was hanged?

1984 — Agent Orange Settlement

public domain images from wikimedia commons

American soldiers received an average of $75 each for being exposed to Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. The hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian people adversely affected by the rain of poison received nothing at all.

Some of the U.S. military veterans received a lot more than the $75 average, but many of the 2.4 million involved in the class-action suit got a much smaller share of the $180 million that Dow, Monsanto, and five other chemical companies agreed to pay out— the amount doled out to individual veterans or their survivors depended on various factors relative to their service (where, when, how long, etc.).

From the early 1960s to the early 1970s, the U.S. military dropped 20 million gallons of herbicides on Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos in order to kill vegetation, thus exposing enemy combatants to view by preventing them of this cover and of the crops that were infected. The defoliants also, of course, poisoned the environment, including the humans exposed to the toxic chemicals.

The chemical companies involved blamed the government, using the defense that they were simply following orders, manufacturing and supplying what they were paid to make and ship. The government countered that argument by saying the companies were motivated by greed, not patriotism.

Questions: Are you, or do you know, any Vietnam vets? Was the compensation you/they received greater or less than the $75 average? Why were the Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian victims of Agent Orange not compensated? Have you seen the documentary GMO OMG? Have you seen the documentary David vs Monsanto? Have you seen the documentary The World According to Monsanto?

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.