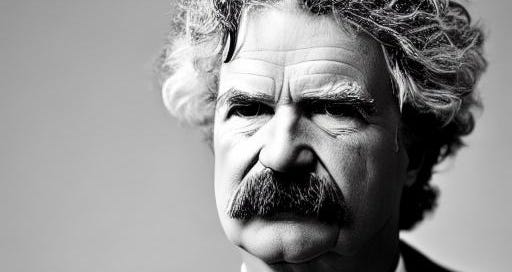

Wheresoever She Was, There Was Eden (Death of Livy, 1904)

Chapter 69 of "Rebel With A Cause: Mark Twain's Hidden Memoirs"

Chapter 69

Wheresoever She Was, There Was Eden (Death of Livy, 1904)In 1904, we returned to Europe—to Florence, Italy, to be more precise—on doctor’s orders. The physicians said that it would be better for Livy’s health to be in a warmer climate. Her physical state had became so perilous that I was under strict orders to not convey any news to her, verbally or in writing, that might excite or distress her in any way. The time even came when I was only allowed to see her for short periods of time once or twice a day, to avoid accidentally telling her something that would upset her.

Nothing could save Livy from the inevitable, though. On June 5th, Olivia, my wife of 34 years, died there in Florence.

Living without her would have been senseless had I not had our daughters Clara and Jean with me yet.

I fell for Livy quickly, first on seeing the ivory miniature of her when I was a passenger on the Quaker City, and then seeing her in person in New York, at the Dickens reading and then at her parents’ house.

But that was just the barest beginning. Love seems the swiftest, but it is the slowest of all growths. No man or woman really knows what perfect love is until they have been married a quarter of a century. And the longer Livy and I were married, the more I loved her and relied on her.

The date of our engagement was February 4th, 1869. The engagement ring was plain and of heavy gold. That date was engraved inside of it. A year later I took it from her finger and prepared it to do service as a wedding ring by having the wedding date added and engraved inside of it—February 2nd, 1870. It was never again removed from her finger for even a moment.

In Italy, when death had restored her vanished youth to her sweet face and she lay fair and beautiful and looking as she had looked when she was girl and bride, they were going to take that ring from her finger to keep for the children. But I prevented that sacrilege. It is buried with her.

EDITOR’S NOTES: In a letter to Twichell a month before Livy’s death, Twain thanked his old friend for a letter which Livy could—for the most part—be allowed to read. Twain wrote concerning this:“You’ve done a wonder, Joe. You’ve written a letter that can be sent in to Livy. That doesn’t often happen when either a friend or a stranger writes. You did whirl in a P.S. that wouldn’t do, but you wrote it on a margin of a page in such a way that I was able to clip off the margin clear across both pages, and now Livy won’t perceive that the sheet isn’t the same size it used to was. It was about Aldrich’s son, and I came near forgetting to remove it. It should have been written on a loose strip and enclosed. That son died on the 5th of March, and Aldrich wrote me on the night before that his minutes were numbered. On the 18th Livy asked after that patient, and I was prepared, and able to give her a grateful surprise by telling her ‘the Aldriches are no longer uneasy about him.’”***Twain began to process his grief over his wife’s death almost immediately, as he would do five years later on the death of his daughter Jean. He wrote of Livy at 11:15 pm:She has been dead two hours. It is impossible. The words have no meaning. But they are true; I know it, without realizing it. She was my life, and she is gone; she was my riches, and I am a pauper. … How grateful I was that she had been spared the struggle she had so dreaded. And that I, too, had so dreaded for her. Five times in the last four months she spent an hour and more fighting violently for breath, and she lived in the awful fear of death by strangulation. Mercifully she was granted the gentlest and swiftest of deaths—by heart-failure—and she never knew, she never knew! She was the most beautiful spirit, and the highest and the noblest I have known. And now she is dead.Twain wrote of his wife that she “poured out her prodigal affections in kisses and caresses, and in a vocabulary of endearments whose profusion was always an astonishment to me.”***In My Father, Mark Twain, Clara Clemens wrote about the event of her mother’s death. She quoted her father in his habitual self-flagellation and blame, as he wrote in a notebook:At a quarter past nine this evening she that was the light of my life passed to the relief and the peace of death after twenty-two months of unjust and unearned suffering. I first saw her thirty-seven years ago and now I have looked upon her face for the last time. . . . I am full of remorse for things done and said in those thirty-four years of married life that hurt Livy’s heart.To the Richard Watson Gilder family, Twain wrote a letter which contained the following passage:An hour ago the best heart that ever beat for me and mine was carried silent out of this house and I am as one who wanders and has lost his way. She who is gone was our head, she was our hands. We are now trying to make plans—WE; we who have never made a plan before, not ever needed to. If she could speak to us she would make it all simple and easy with a word, and our perplexities would vanish away. If she had known she was near to death she would have told us where to go and what to do, but she was not suspecting, neither were we. She was all our riches and she is gone; she was our breath, she was our life, and now we are nothing.And in a letter Twain wrote to his daughter Clara, he quoted a paragraph from a note of condolence sent to him from his friend Helen Keller, which was:Do try to reach through grief and feel the pressure of her hand, as I reach through darkness and feel the smile on my friends’ lips and the light in their eyes though mine are closed.The loss of Livy was such a sore spot for Twain even four years later that he could not bring himself to attend the wedding of a friend and, in fact, poured out his ongoing grief in his reply to that invitation, writing just before moving into his final residence, “Stormfield”:Marriage—yes, it is the supreme felicity of life. I concede it. And it is also the supreme tragedy of life. The deeper the love, the surer the tragedy. And the more disconsolating when it comes.And so I congratulate you. Not perfunctorily, not lukewarmly, but with a fervency and fire that no word in the dictionary is strong enough to convey. And in the same breath and with the same depth and sincerity, I grieve for you. Not for both of you and not for the one that shall go first, but for the one that is fated to be left behind. For that one there is no recompense. For that one no recompense is possible.There are times—thousands of times—when I can expose the half of my mind and conceal the other half. But in the matter of the tragedy of marriage I feel too deeply for that, and I have to bleed it all out or shut it all in. And so you must consider what I have been through, and am passing through, and be charitable with me.Make the most of the sunshine! And I hope it will last long—ever so long.I do not really want to be present. Yet, for friendship’s sake and because I honor you so, I would be there if I could.Most sincerely your friend,S. L. ClemensTwain also included the following eulogy of his wife in his autobiography:I saw her first in the form of an ivory miniature in her brother Charley’s stateroom in the steamer Quaker City in the Bay of Smyrna, in the summer of 1867, when she was in her twenty-second year. I saw her in the flesh for the first time in New York the following December. She was slender and beautiful and girlish—and she was both girl and woman. She remained both girl and woman to the last day of her life. Under a grave and gentle exterior burned inextinguishable fires of sympathy, energy, devotion, enthusiasm and absolutely limitless affection. She was always frail in body and she lived upon her spirit, whose hopefulness and courage were indestructible.Perfect truth, perfect honesty, perfect candor, were qualities of my wife’s character which were born with her. Her judgments of people and things were sure and accurate. Her intuitions almost never deceived her. In her judgments of the characters and acts of both friends and strangers there was always room for charity, and this charity never failed. I have compared and contrasted her with hundreds of persons and my conviction remains that hers was the most perfect character I have ever met. And I may add that she was the most winningly dignified person I have ever known. Her character and disposition were of the sort that not only invite worship but command it. No servant ever left her service who deserved to remain in it. And as she could choose with a glance of her eye, the servants she selected did in almost all cases deserve to remain and they did remain.She was always cheerful; and she was always able to communicate her cheerfulness to others. During the nine years that we spent in poverty and debt she was always able to reason me out of my despairs and find a bright side to the clouds and make me see it. In all that time I never knew her to utter a word of regret concerning our altered circumstances, nor did I ever know her children to do the like. For she had taught them and they drew their fortitude from her. The love which she bestowed upon those whom she loved took the form of worship, and in that form it was returned—returned by relatives, friends and the servants of her household.***Katy Leary, who was employed by the Clemens family for thirty years as ladies’ maid and seamstress, was with Susy when she died in 1896, with Livy when she died in 1904, was the first to discover Jean after she died in 1909, was with Twain when he died in 1910, and present at the birth of Twain’s only grandchild four months after Twain’s death. In Mary Lawton’s book A Lifetime with Mark Twain: The Memories of Katy Leary, for Thirty Years His Faithful and Devoted Servant, Katy recounts a scene in the Clemens home after she had returned there from an errand. Katy immediately inquired of Livy’s nurse:“How is Mrs. Clemens?” She said: “She is not so well, she’s having a bad spell. I am going to give her some oxygen.” I hurried to her room on the ground floor, to get it ready, and when she saw me she whispered: “Oh! I’ve been awful sick all the afternoon, Katy.”“Well,” I says, “you’ll be all right now.” And I held her up, held her in my arms, and I was fanning her and then—then she fell right over on my shoulder. She died right then in my arms. She drew a little short breath, you know, just once, and was gone! She died so peaceful and a smile was on her face. I looked at her—and I knew that was the end. I knew she’d gone. I couldn’t hear her breathe any more. I lay her back on the pillow and ran out to get the family. They had all been right around her only a few minutes before, and had left because the nurse thought it best for her to be alone.Miss Clara was in the parlor and Mr. Clemens was in the dining-room, waiting. Oh! I don’t know how I told them. I guess I didn’t have to—they knew…. They came into the room and oh, God! It was pitiful. Mr. Clemens ran right up to the bed and took her in his arms like he always did and held her for the longest time, and then he laid her back and he said, “How beautiful she is—how young and sweet—and look, she’s smiling!”It was a pitiful thing to see her there dead, and him looking at her. Oh, he cried all that time, and Clara and Jean, they put their arms around their father’s neck and they cried, the three of them, as though their hearts would break. And then Clara and Jean, they took their father by the hand, one on each side, and led him away…. I dressed Susy for her burial, and I dressed Mrs. Clemens for hers, and then, later on, I dressed Jean.***In his 1905 sketch Extracts from Adam’s Diary, casting himself and his wife in the roles of the first human pair, Twain has Adam say of Eve: “Wheresoever she was, there was Eden.”***When Twain’s youngest daughter Jean was nine, he had been receiving invitations to meet various dignitaries. When the Emperor of Germany invited the Clemens family to dinner, this made quite an impression on Jean. She said to her father, “Why, papa, if it keeps going on like this, pretty soon there won’t be anybody left for you to get acquainted with but God!” Twain’s reaction to that observation was that it was not complimentary to think that he was not already acquainted in that quarter, but that Jean was young, and the young sometimes jump to conclusions without reflection.Corroborating Jean’s observation, in the middle of 1904 (shortly before Livy’s death) Twain wrote the following in a letter to Twichell, speaking about the death of his friend Henry Stanley (he of the much-ballyhooed “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” interrogation):I believe the last country house visit we paid in England was to Stanley’s. Lord, how my friends and acquaintances fall about me now in my gray-headed days! I had known Stanley 37 years. Goodness, who is it I haven’t known! As a rule the necrologies find me personally interested—when they treat of old stagers. Generally when a man dies who is worth cabling, it happens that I have run across him somewhere, some time or other.The amazon page for “Rebel With a Cause: Mark Twain's Hidden Memoirs” is here.

Free writings of mine can be read or downloaded here.