The Mysteries of History (May 17 Edition)

7 Years War Begins; Brown v Board of Education; Watergate on TV; Million Person Protest in China

1756 — World War 0 Begins in Europe

public domain image from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the Seven Years War in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

Seven years of bad luck, the good things in your past —from the song “Superstition” by Stevie Wonder

The War known in America as the French and Indian War, but in Europe as the Seven Years War, began (officially) this year. One way to view it is that they were two wars, one fought in Europe (the Seven Years War) and one fought in America (the French and Indian War). Another way to view the situation is that they were both the same war, just with different names, simultaneously fought in different locales. Whatever the semantics of the matter may be, some historians view this as the first world war. At stake was which Euro pean superpower would control North America.

By this year one million British subjects were living as colonists in America, compared with just 55,000 French citizens. Despite the huge differential in sheer numbers, the French were more widely scattered throughout the continent, having pressed far west in their search for fur. In contrast with the 2,000 miles the French had roamed westward, the British had concentrated their settlements on the east coast, on the eastern slope of the Appalachians.

Besides having a wider base of operations, another advantage the French enjoyed was that they could count more Indians as allies than the British could. The French, more willing to mix with the Indians (many Frenchmen married Indian women), were considered by many Indian tribes as the lesser of two evils. The French were also more amenable to learning from the Indi ans. One lessen the French took to heart was the Indians’ wilderness battle tactics. The British, on the other hand, at first erroneously attempted to fight a European-style war in a frontier setting—attempting, in effect, to put old wine into new wine skins.

On this date in 1756, England declared war on France, officially touching off what became known in Europe as the Seven Years War and in America as the French and Indian War (because the British colonists, who named the war, were fighting against the Native Americans and their European allies, the not-as-bad-as-the-British (according to the Native perspective) French colonizers.

The British and its allies, including the American colonists, fought both a hot and cold war against France and its allies throughout a large swath of the world — not just across Europe and North America, but also India.

As the great powers of Europe were all involved in the war (Austria, Prussia, Russia, Saxony, and Sweden), this could actually be called World War 1, but since that name is already taken, perhaps World War 0 would be a better label for it, replacing both “The Seven Years War” and “The French and Indian War.”

Britain’s belligerence against France and Spain in America aided the Americans; and France’s bitterness over the war ended up also aiding the Americans later, when the American colonists rebelled against Britain and were supported by Britain’s old nemesis, France.

Questions: How would history have been affected if Britain had not declared war on France in 1756? Would the Americans have been able to defeat Britain in the 1770s without France’s backing? Without America’s successful Revolution, would France have had a Revolution of its own shortly thereafter?

1954 — Brown Fights the Board

public domain images from wikimedia commons

The following is what I wrote about the desegregation of schools in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

“In the first place God made idiots; that was for practice; then he made school boards.”—Mark Twain

. . .

Almost a century after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the Union’s successful conclusion of the Civil War, racial segregation in schools was made legally untenable this year.

Oliver Brown lived just four blocks from an all-white school. The run down all-black school, where Brown’s third-grade daughter was expected to attend, was all the way across town. Brown attempted to enroll Linda in the nearer school, but was informed by the school board that he could not do that. Brown sued the school board. As similar lawsuits were being simultaneously brought elsewhere throughout the country, they were tried together, and before the Supreme Court, no less.

Because the surname Brown came first alphabetically among the litigants, the composite case was known as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

In this landmark case, the Supreme Court reversed the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, which had validated the practice of separate facilities (such as rest rooms, water fountains, seating areas in movie theaters, etc.) for the races, albeit supposedly “equal but separate” (which was virtually never, if ever, really the case).

The wheels of justice are often slow in turning. Brown had attempted to enroll his daughter three years earlier, in 1951. In 1953, the case was finally heard by the Supreme Court. It wasn’t until this year of 1954 that a decision was reached.

Thurgood Marshall, who would later serve on that august body, was at the time a NAACP lawyer, fighting the case for Brown, et al. The Supreme Court justices were split until the Court’s chief justice Fred Vinson died. Former California Governor Earl Warren took his place in that position.

Warren felt it was necessary for the court to present a united front on this issue. He was able to gradually persuade all the justices to his way of thinking, and his goal of a unanimous decision was, in the end, achieved. Warren summarized the Court’s decision, writing that “In the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” The new Chief Justice added that “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

As parents everywhere know, though, it is one thing to enact a law, and another thing altogether to enforce it. Nevertheless, a precedent was being set for the future. Within the next few years, public transportation and restaurants would be integrated, albeit only after much suffering.

In his book “Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement,” which chronicles the Civil Rights movement, John Lewis, a very active participant in that movement, wrote of his reaction on finding out about the court’s decision in the Brown case:

Near the end of my freshman year, on a May morning in 1954, I read something that stunned me, just absolutely turned my world upside down. The U.S. Supreme Court had finally handed down its decision in the school desegregation case of Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka. The ruling declared that the “separate but equal” doctrine, on which almost the entire institution of segregation was based, was unconstitutional. I remember the feeling of jubilation I had reading the newspaper story—all the newspaper stories—that day. Everything was going to change now. No longer would I have to ride a broken-down bus almost forty miles each day to attend classes at a “training” school with hand-me-down books and supplies. Come fall I’d be riding a state-of-the-art bus to a state-of-the-art school, an integrated school.

It was not to be that easy, though. Lewis went on to report about the back lash:

All that spring I searched the papers for news of Alabama’s plans for desegregating its schools. Instead, what I saw were stories quoting state politicians derisively referring to the day of that Supreme Court decision as Black Monday and making clear that they had no intention of obeying the ruling. I read about branches of something called White Citizens Councils—coat-and-tie versions of the Ku Klux Klan—forming in Georgia and Mississippi. As for the Klan itself, there were reports of hooded marches and midnight cross burnings across the state of Alabama. I heard talk that summer of black men being beaten and even castrated—not in Pike County, but in places just like it. I didn’t know if that talk was true, but I didn’t doubt it was possible…as I began my sophomore year in the fall of 1954 by climbing onto the same beat-up school bus and making the same twenty-mile trip to the same segregated high school I’d attended the year before. Brown v. The Board of Education notwithstanding, nothing in my life had changed.

The ruling was a sign of hope for black Americans. They had been prom ised many things before, though, by white America. As civil rights activist and lawyer Charles Houston put it, “Nobody needs to explain to a Negro the dif ference between the law in books and the law in action.”

It was a start, though. This year is, in fact, considered the beginning of the modern Civil Rights moment, which ran, according to the producers of the book and video series “Eyes on the Prize,” from 1954–1965. It was doubtless an impetus to the Montgomery bus boycott, which would begin three months after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling was handed down.

Linda Brown, whose skin was brown, was the student for whom the lawsuit was named but, of course, she stood for many others. The Board of Education were apparently bored of education, because they had to be forced to learn a lesson and do the right thing (allow Linda to attend the closer and better-equipped school, which happened to be a “white” school at the time, rather than have to travel further to a less-well-equipped “black” school). The ruling in favor of Brown benefited not just Brown herself, but many others thereafter, including those who would not have otherwise been able to get to know people of another race.

Today, some school districts are clamoring to rid themselves of federal mandates at desegregation, claiming it is not longer needed. They are basically asking to be trusted to do the right thing. Does this sound like possibly the fox asking to be made guardian of the henhouse? If they are sincerely resolved to do the right thing, why are they chafing at the law?

Questions: Have you read the book The [Star-Bellied] Sneetches by Dr. Seuss? Have you heard Ray Stevens’ song Everything is Beautiful (especially the prologue)?

1973 — Boobs on the Boob Tube (Watergate “Plumbers” & Their Puppeteer)

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Hearings into the dirty, rotten tricks President Richard Nixon and his henchmen had been up to began to be televised on this date in 1973.

Besides the shenanigans in the Watergate hotel, with Nixon’s minions breaking into Democratic offices to try to gain an upper hand in the Presidential election, it was discovered that Nixon’s gang of dirty-deeders had been spying on thousands of American citizens, to boot.

Archibald Cox, a Harvard law professor, was appointed to serve as special Watergate prosecutor. When it was learned that much of the illegal activity that was being investigated had been orchestrated by Nixon himself, and that there were extensive tape recordings of conversations in the White House proving this, Cox subpoenaed those recordings. Nixon procrastinated for months before finally saying he would supply a summary of what the recordings contained. This was not good enough for Cox; he demanded all of the recordings. Nixon then fired him. Cox was replaced by Leon Jaworski, who indicted some of Nixon’s top sycophants, who were subsequently convicted.

Nixon’s reputation was in the toilet, and the Senate proceeded to impeach him on three grounds: obstruction of justice, abuse of presidential powers, and hindrance of the impeachment process.

When Nixon finally reluctantly and grumblingly handed over the damning tapes, he concluded his chances of being cleared of the charges were akin to that of a snowball in a furnace, and so in early August became the first U.S. President to resign from office. Vice President Gerald Ford took over as President. Ford pardoned Nixon of all crimes the next month.

Questions: Which U.S. Presidents besides Nixon have a reputation for being corrupt? Have you heard of the Teapot Dome Scandal? Do you think Ford was right in pardoning Nixon? What are the arguments for and against him doing so?

1989 — Million Person Protest in Beijing

public domain image from wikimedia commons

On this date in 1989, one million Chinese citizens gathered to protest the form of rule they were living under, demanding more input in Government decisions.

The Chinese government was not amused by this display of dissatisfaction on the part of its citizens. The measures the government took against the protesters became ever harsher — arrests, beatings, and even murder.

The government’s response was reminiscent of the Kent State, Ohio murder of students in 1970 written of in the Four Dead in Ohio article here — but on a much grander scale, with thousands killed and upwards of 10,000 detained. The brutal crackdown became known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

Questions: What exactly did the protesters want? What exactly was it that the government was unwilling to do for its people? What was so important to those in power that they were willing to kill thousands of their own citizens? What level of frustration and hopelessness do people have to reach before they take the risk of protesting against an institution that holds power of them, whether that power be family, school, employer, local government, State government, or Federal government? Do you think it’s best to just “settle” for things as they are not “rock the boat”?

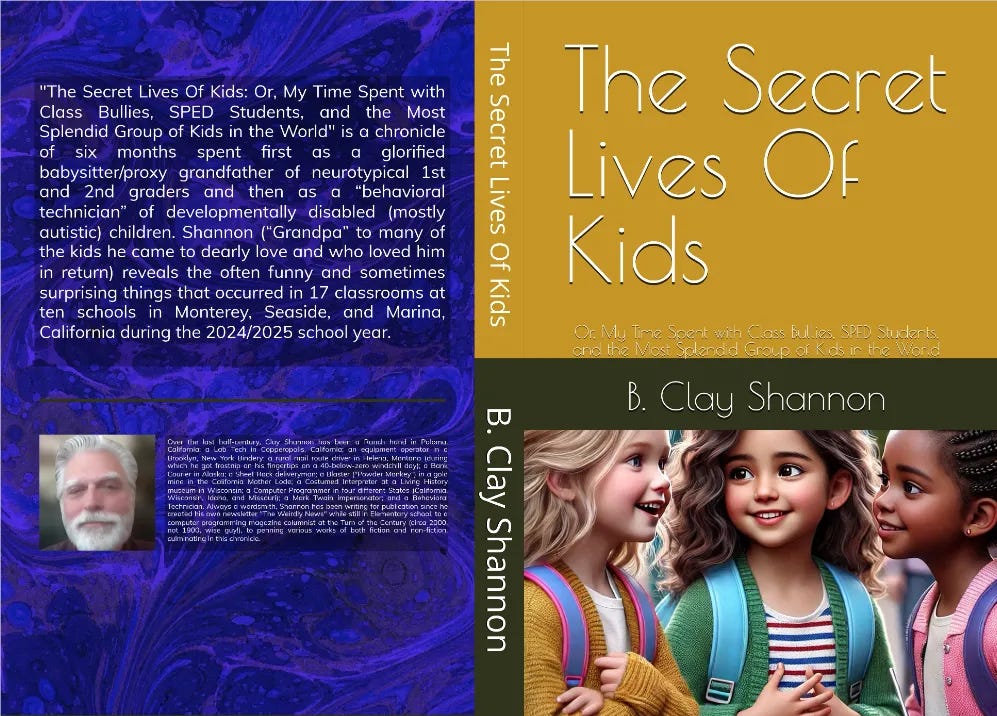

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.