1896 — Plessy v. Ferguson

public domain image from wikimedia commons

Almost exactly 58 years before the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision reversed the constitutionality of “Separate but Equal” (as you can read about here, in the “1954 — Brown Fights the Board” article in yesterday’s post), the same Court (but made up of different justices) ruled that “separate but equal” was constitutional, and thus that segregation was not necessarily discriminatory.

The “rest of the story” (some of it, anyway) can be found below.

Public domain image

The following is what I wrote about Plessy v. Ferguson in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 1: 1620-1913:

In a landmark Supreme Court case, Plessy v. Ferguson, it was decided by that body this year that “separate but equal” accommodations for blacks on railroad cars did not violate the 14th amendment’s clause promising “equal protection under the laws.”

The case came about when Homer Plessy (who was one-sixteenth black) refused to move from his seat to the car where the blacks were relegated to sitting while on a train in Louisiana. After being arrested and put off the train, Plessy sued the railroad, arguing that segregation was unconstitutional.

The veneer of supposed reasonableness and fairness promulgated by “separate but equal” was transparent to at least one justice. John Marshall Harlan, the court’s lone dissenter, stated his opposing opinion that “The thin disguise of ‘equal’ accommodations…will not mislead anyone.”

With the Supreme Court’s seal of approval and go-ahead signal, the stage was set for the discriminatory set of laws the south would enact, which came to be known as “Jim Crow” laws. These laws made it illegal for the races to use the same schools, restaurants, restrooms, water fountains, etc. Additionally, blacks were expected to tip their hats to whites if they happened to meet on the street, although whites were not even required to remove their hats when entering a black family’s home. Blacks were to call whites “sir” and “ma’am,” but whites called blacks by their given names. When sharing a sidewalk, blacks were to give whites a wide berth, stepping out of the way to let the lighter-skin people pass unimpeded. An especially extreme example of Jim Crowism was practiced in South Carolina, where cotton-mill workers even had race-specific windows—blacks were not to peer out of the windows assigned the whites, and (presumably) vice versa.

Questions: Again (I’ve asked this before): Have you read the Book “The Sneetches” by Dr. Seuss? And also again: Have you heard the Ray Stevens song Everything is Beautiful, especially the intro? As we are all cousins (our family trees meet at some point in the past), does it make sense to classify people based on how much of this race or that ethnicity they are? Even if we were not all related, would it make sense or be fair to be prejudiced toward anybody?

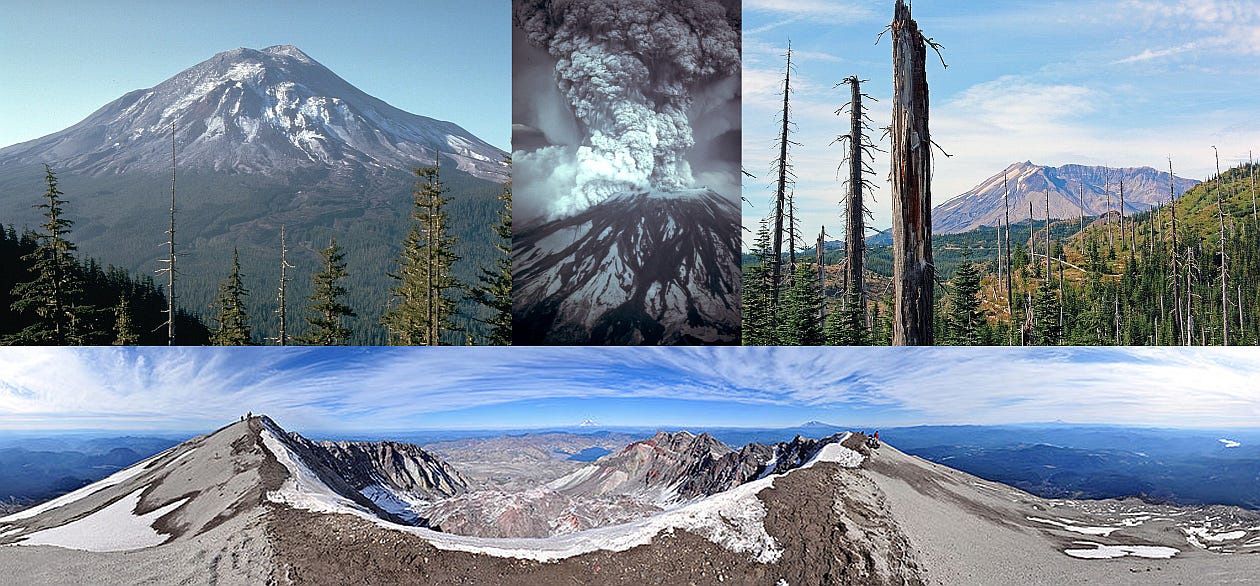

1980 — Mt. St. Helens Wakes Up Angry

public domain images

The following is what I wrote about the eruption of Mt. St. Helens in my book Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History — Volume 2: 1914-2006:

“No one knows more about this mountain than Harry, and it don’t dare blow up on him.”—Harry Truman, before Mt. St. Helens blew its top

“The moon looks like a golf course compared to what’s up there.” —Jimmy Carter, after viewing the Mt. St. Helens devastation

. . .

Mt. St. Helens, in Washington State, which had been threatening to pop off since March 27th, when an ominous bulge was detected on its north slope, erupted on May 18th. The birds were eerily silent that morning. People soon found out what wildlife apparently already knew was going to happen.

The mountain erupted in a stupendous cataclysm five hundred times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Fifty-seven people who had not heeded the mountain’s clear warnings died. The giant mass of dirt, rock, vegetation, and lava had actually already erupted several times in the days and weeks leading up to May 18th, but this was “the big one”—the deadliest volcanic eruption in U.S. history.

The blast was felt from a distance of one hundred miles. The cloud of ash the eruption unleashed completely darkened the skies as much as eighty-five miles away. The crater that opened on the mountaintop measured a mile across. The winds generated by the blast knocked down trees like dominoes. At least a dozen fires were ignited as a result of the superheated gas and ash and hot mud.

The mountain belched forth massive amounts of hot gas in addition to the cubic tons of ash, which turned the mountainsides into rivers of hot mud. Mud slides demolished 123 houses in the nearby town of Toutle. Portland Harbor was jammed with mud, and the Columbia River was blocked for twenty miles with trees that had been flattened and then carried into the river.

Across the entire northwest, almost six thousand miles of roads were cov ered with ash which had the consistency of wet cement. The ash cloud that spewed forth from the innards of the mountain reached proportions of five hundred miles in length and one hundred miles in width and traveled east ward across Idaho and Montana.

Those who perished in the ensuing blast and hellacious outpouring of lava and gas included Harry Truman. No, not that Harry Truman, the one who had himself given the go-ahead for conflagrations of a different type to rain down on Japan in 1945. This Harry Truman was an eighty-four-year old gent who lived with his seventeen cats on Mount Saint Helens five miles from the volcano. Harry said he would never leave, regardless of the danger or the con sequences of his obstinacy.

Harry was right about that—he didn’t leave, and still hasn’t. He is entombed deep beneath an accumulation of solidified mud that completely covers his former home, himself, and—presumably—his seventeen cats.

Other casualties of the cataclysm included thrill-seekers, and photographers who were willing to take any risk to get “the shot.” These paid the ultimate price for their pursuit of glory, cash, art, historical artifacts, or whatever it was they were so intent on accumulating.

Besides the human lives lost, fifteen hundred elk, five thousand deer, and an estimated eleven million fish died. As to material damage, two hundred homes, forty-seven bridges, fifteen miles of railroad track and 185 miles of highway were destroyed. After Mt. St. Helens literally blew its top, its height was reduced from 9,677 to 8,364 feet.

Ash that had been belched out of the mountain’s depths spread upwards and outwards, drifting for hundreds of miles, darkening the sky, dropping temperatures, and creating a muddy mess in areas where it was simultaneously raining. The sky was hazy and cars were covered with up to several inches of the gray ash. A disaster to a relatively small number of people, it was a nuisance to manifold more. The nutrient-rich ash proved to be a boon to farmers in the coming growing seasons, though.

The natural disaster was another reminder to mankind that he can only rein in “Nature” to a very limited degree—when it wants to release pressure, it will, and you had best just get out of the way.

Native Americans called it Louwala-Clough (“the Smoking Mountain) for good reason. It had erupted many times throughout history, but the time it did at 8:32 in the morning on this date 45 years ago was especially catastrophic: 57 people died, and 210 square miles were laid desolate.

Mount St. Helens had been dormant for over a century. The violent earthquake, eruption, and avalanche did not come without warning — the mountain had been “acting up” for a couple of months before its cataclysmic venting and spewing in 1980. Once the mountain was seen to be bulging, evacuations began for those who lived at its base. Some, though, such as Harry Truman (1896-1980), refused to leave.

The blasts from the exploding mountain traveled both outward and upward, leveling around 10 million trees. The debris that was released traveled at 100 miles per hour. Ash spread hundreds of miles. In addition to the 57 humans, thousands of animals and millions of fish died.

Mount St. Helens’ elevation was reduced from 9,680 feet (almost two miles) to 8,363 feet. It has been active again in the meantime (e.g. in 2004, 2005, and 2008), but not nearly to the same extent as 1980 — yet, anyway.

Questions: If you were alive in 1980, do you remember the Mount St. Helens eruption? Were you personally affected by it? What natural disaster is most likely to occur where you live? What can you do to prepare for it?

Read about “The Secret Lives of Kids” here.